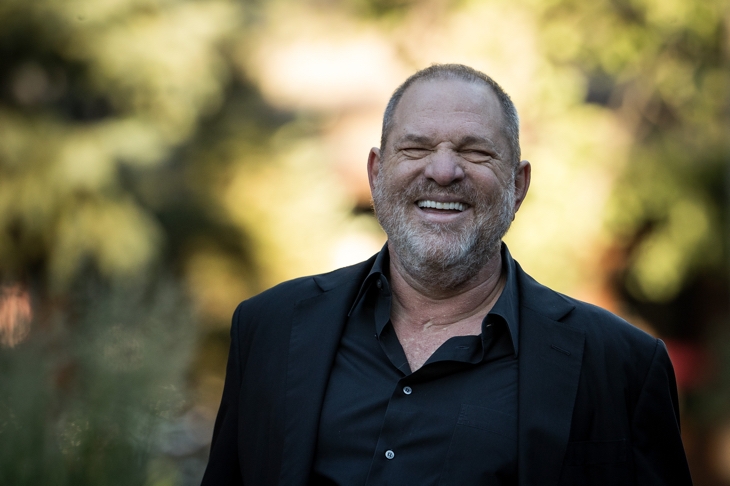

Why are all the women involved in the Harvey Weinstein allegations only speaking out now? That question has been asked repeatedly – including on this blog – since the accusations against the film mogul first emerged. Why now? Ross Clark suggested on Coffee House yesterday that women who had achieved what some of the actresses and UN goodwill ambassadors had managed should be brave enough to speak out about someone who appears to have been a serial predator over many years – but that they failed to do so because their allegations date back to when they were ‘on the make’.

It’s a fair point, isn’t it? But isn’t it just a little odd that a slightly different species of fair point tends to appear whenever any sort of woman complains about abuse and assault? There’s the ‘fair point’ about a woman wearing certain clothes and drinking a certain amount, ending up in a certain place with a certain man. There’s the ‘fair point’ about the woman who went home to the husband who abused her night after night, year after year when she could have just left him. There’s the ‘fair point’ about the woman who took a few years even to tell one person that she was raped when she should have gone straight to the police so they could collect the necessary medical evidence.

So many fair points to make about how a woman didn’t quite get it right. Sure, sexual predators are the ones who choose to do the wrong thing, the ones who should stop and who should feel the full force of the law. But if only the women had complained in the right way and at the right time. Then others wouldn’t have fallen prey to monsters too.

Another fair point is that other women should speak out about the abuse they’ve heard about in their industry, even if they haven’t witnessed it first hand. Unless women at the top of their tree speak out, what hope is there for the vulnerable women trying to work their way up?

The problem with these fair points is that even when they acknowledge that a man has done a bad thing to a woman, they involve the woman being blamed for the circumstances she found herself in, or what she did afterwards. They don’t take account of the possibility that wearing certain clothes or being in a hotel room where people start to melt away one by one doesn’t actually constitute consent. They don’t take account of the fact that sexual assault and abuse are weapons that men use to gain power over their victims. They are about control, and that control remains firmly in place once the visible offence is over. A victim of abuse will believe the fair points that suggest that if only she’d protested a bit louder, spoken out at the right time, or not gone back home to the man who told her she was nothing without him, then this would have been real abuse, rather than the sort of abuse that someone sort of brought on themselves one way or another.

Joanna Williams claims today on Coffee House that the #metoo trend where women post on social media that they too have been victims of sexual harassment of one kind or another is ‘an unedifying clamour to be included in celebrity suffering’. Perhaps, but then again perhaps it would be better if the rest of us didn’t join the unedifying clamour to sneer at other people. Sneering makes us feel better about ourselves temporarily, but it doesn’t really contribute much to the advancement of humanity, does it? It certainly isn’t what someone who had been assaulted would look for in the friend they finally turn to. And it certainly doesn’t help us understand one another better and learn to live alongside each other.

Over the past year, I’ve been doing some fundraising and work with domestic abuse charities. Two things shocked me. The first was that most of the survivors of abuse – whether domestic violence or sexual assault – that I met hadn’t gone to the police about what happened to them because they were terrified that they just wouldn’t be believed or that someone would confirm their own deep fear that the abuse was actually their fault after all (it never is). These weren’t just obviously ‘vulnerable’ women: they were the ‘brave’ sort that Ross seems to imagine should have no trouble with reporting what happened. They were lawyers, businesswomen, doctors.

The other was that I didn’t need to go out to meet survivors, because they started appearing in my inbox. They were my friends: women I had known for years, messaging me to tell me that they had seen I was working with Refuge and could they tell me about what their boyfriend, or husband, or relative had done to them? I had previously thought that sexual assault and domestic violence weren’t all that widespread, but I realised that it’s not just in Hollywood that there seems to be a suspicious number of victims hiding in the woodwork. There are a suspicious number of victims in all spheres: it’s just that they don’t tend to speak out until they have confidence that they will be believed.

I have realised that the most suspicious thing about our society is not that women wait to report abuse, but that we have ended up so cold and lacking in empathy that they fear doing so. Surely society can be brave enough to face up to its failings, rather than sneering at the people who end up being victims?

Comments