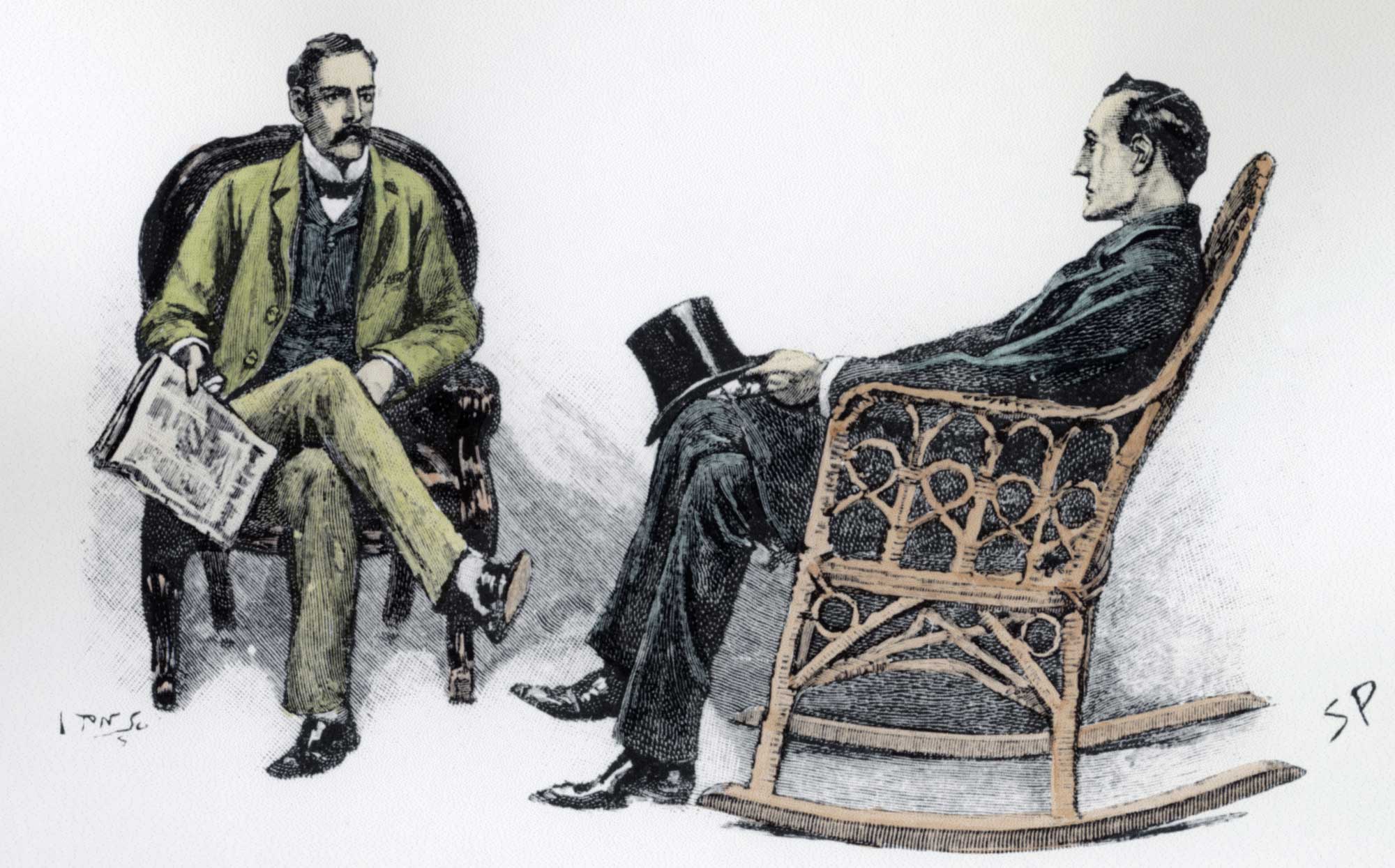

There is no better time to read a Sherlock Holmes story than a winter evening. As the rain lashes against the windows and the fog descends, we can imagine ourselves sitting companionably with the great detective and the good doctor around the Baker Street hearth, waiting for the step of a visitor upon the stair.

Unfortunately, our 21st-century climate rarely cooperates. The rainstorm arrives when we’re far from a hearth, fighting with an umbrella that turns inside-out at the first breath of wind. And when were you last enveloped in a London fog? The savagery of the elements beating down on 221b seems to belong to another world. ‘It was a wild, tempestuous night, towards the close of November… Outside the wind howled down Baker Street’ (‘The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez’). ‘The storm grew higher and louder, and the wind cried and sobbed like a child in the chimney’ (‘The Five Orange Pips’). ‘I doubt whether it was ever possible from our windows in Baker Street to see the loom of the opposite houses’ (‘The Bruce- Partington Plans’).

Curiously, though, it rarely snows in Holmes’s London – and just one of the 60 mysteries, ‘The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle’, published in the Strand magazine in 1892, is set at Christmas.

That story begins with the newly married Dr Watson dropping in on his former flatmate to wish him the compliments of the seasons. Suddenly the building’s commissionaire rushes in to show Holmes what he has found in the crop of his festive goose – ‘a brilliantly scintillating blue stone’. It is the fabulous blue carbuncle stolen from the Countess of Morcar five days earlier.

But hang on – geese don’t have crops. That may strike you as a trivial detail, but dedicated Sherlock Holmes fans, known as Sherlockians, revel in such discrepancies. There are hundreds of inconsistencies in ‘the Canon’ (the four Holmes novels and 56 short stories). I should know: I’ve been an obsessive Sherlockian since childhood. My bookcase is bursting with Sherlockiana, including all the bound Strand magazines containing the short stories illustrated by Sidney Paget, a copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles signed by Arthur Conan Doyle and three annotated sets of the complete Canon.

The multi-volume Sherlock Holmes Reference Library edited by Leslie S. Klinger devotes two pages to the problem of geese’s nonexistent crops, which Holmes fanatics have been debating ever since one Miss Mildred Sammons pointed it out in a letter to the Chicago Tribune in 1946. This prompted Sherlockians to consult ministers of agriculture, veterinary surgeons and butchers. Was Watson referring to the goose’s lower gullet, which might conceivably conceal a stolen jewel? Or had his editors altered the vowel in ‘crop’ from an ‘a’ to an ‘o’ in order to avoid offending Victorian sensibilities?

You’d be forgiven for thinking that Sherlockians are mad. We are, but there’s a method to our madness. It’s called ‘playing the game’. On the face of it, there’s an obvious solution to the mystery of the crop. For Conan Doyle, the Holmes stories were a distraction from his historical novels, so he dashed them off without checking details; later in ‘The Blue Carbuncle’ he underlines his ignorance of London by having Holmes and Watson question a poultry dealer in Covent Garden fruit and vegetable market, which is like going to Smithfield to buy bananas. But when Sherlockians play the game, they pretend that Dr John H. Watson was a real person faithfully recording the detective’s cases. They employ the techniques of advanced scholarship to explain why, for example, in The Sign of Four Holmes and Watson set out for the Lyceum Theatre in July but arrive there on a cloudy September evening.

The game was invented in 1911 by the future Monsignor Ronald Knox when he was a junior fellow at Trinity College, Oxford. His paper ‘Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes’ was intended to parody the earnest attempts of liberal Protestant scholars to account for contradictions in the Bible. An early convert to the game was Dorothy L. Sayers, who stirred up a ferocious, never-settled controversy over whether the young Sherlock was educated at Oxford or Cambridge. (She opted for the latter – wrongly, in my opinion.)

Dorothy L. Sayers stirred up controversy over whether Sherlock was educated at Oxford or Cambridge

It was a former Rhodes scholar, the newspaper columnist and novelist Christopher Morley (1890-1957), who was responsible for planting Sherlockianism in North America. Morley was the most industrious trencherman in Manhattan. He liked to turn his three-hour lunches into impromptu literary societies, one of which he named the Baker Street Irregulars (BSI) after the street urchins recruited as spies by Sherlock Holmes.

Founded in 1934, the BSI is older than the Sherlock Holmes Society of London. Compared with their more reticent cousins, the Irregulars play the game with mock-solemn gusto, which British cynics might say is what happens when Americans adopt Anglophile customs. But that would be churlish. The Baker Street Irregulars are unlike any other literary society in the world.

Membership is strictly invitation-only. New Irregulars are ‘invested’ at an annual dinner celebrating Holmes’s supposed birthday on 6 January. (The tarnishing of that date has not gone down well; many Sherlockians would happily tip Donald Trump into the Reichenbach Falls.) At the same time, however, the BSI encourages the flourishing of ‘scion societies’ and their Canadian equivalents, most of which are open to anyone.

There are around 200 active Sherlockian groups in North America. This month alone there have been meetings of the Stormy Petrels of Vancouver, the Hansom Wheels of Columbia, Dr Watson’s Neglected Patients in Denver, the Notorious Canary-Trainers of Madison, the Sound of the Baskervilles in Seattle and the Bootmakers of Toronto. The Norwegian Explorers of Minnesota, founded in 1948, are holding their annual dinner, while the Afghanistan Perceivers of Oklahoma and the Illustrious Clients of Indiana-polis are both staging Blue Carbuncle celebrations.

There will also be one of the monthly ‘ASH Wednesday’ dinners of the Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes. Mattias Boström, in his Life and Death of Sherlock Holmes, describes the bizarre genesis of this group. On a bitterly cold winter’s day in January 1968, the all-male BSI dinner at Cavanaugh’s Restaurant, New York, was picketed by teenage female Sherlockians ‘dressed in animal-patterned fake furs, miniskirts, fishnet stockings and high heels’. The BSI invited them in for a drink in the downstairs bar – but it was not until 1991 that women were invested.

That move was long overdue. Women Irregulars have blown the cobwebs off the game. For example, Dr Mary Alcaro, an authority on the literary impact of the Black Death, is also a qualified bartender who creates ‘Sherlocktails’; her ‘Jabez Wilson’, named after the pawnbroker from ‘The Red-Headed League’, is a flame-coloured mixture of gin, Campari and ginger ale. Monica Schmidt, a clinical psychologist, has made a plausible argument that the wounded Afghan veteran Watson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. She also addresses the fascinating question: how high do you get if you inject yourself with a 7 per cent solution of cocaine?

All of which makes our home-grown Sherlockians sound less fun than the Americans. Certainly we’re less consumed by the hobby. But in other respects Britain calls the tune. Countless BSI members discovered Holmes through the Granada television series starring Jeremy Brett. Younger enthusiasts fell in love with Benedict Cumberbatch in the BBC’s Sherlock, which began stylishly but curdled into preachiness and digital trickery. And now we have Sherlock & Co, an audio podcast that updates Conan Doyle with far greater ingenuity than Sherlock.

Joel Emery’s scripts and Adam Jarrell’s direction play audacious tricks with the plots while filling the episodes with subtle homages that even a seasoned Sherlockian might miss. Toilet jokes alternate with pitch-perfect satire: the few seconds of fake Joe Rogan in ‘Silver Blaze’ are alone worth the price of admission. Yet the crimes are chilling. The ten-episode Hound of the Baskervilles may be the most frightening adaptation ever.

It’s heresy to say so, but the plots are less interesting than the relationship between Holmes and Watson

Most daringly, Sherlock & Co turns the Baker Street duo into a trio. Harry Attwell’s autistic Holmes and Paul Waggott’s chirpy Watson are joined by Mariana, the detective agency’s Spanish business manager, played by Marta da Silva. You’ll have to listen for yourselves to discover exactly how it works, but the general principle is one spelled out by Christopher Morley in 1944: that the Sherlock Holmes stories can be understood as ‘a textbook of friendship’, a quality displayed most touchingly around the Baker Street fireplace.

It may be Sherlockian heresy to say so, but the plots in the Canon are ultimately less interesting than the relationship between Holmes, the ‘perfect reasoning machine’ with a mischievous streak, and the carefully etched character of Watson. But perhaps the most precious feature of the stories is the atmosphere created by Conan Doyle. He was writing just as Dickensian London was giving way to suburbia. That unique moment enabled him to create a fusion of the Gothic and the domestic whose appeal is magically captured in a poem that many Sherlockians know by heart – Vincent Starrett’s ‘221b’, written in America to warm the hearts of Londoners during the darkest days of the second world war:

A yellow fog swirls past the window-pane

As night descends upon this fabled street:

A lonely hansom splashes through the rain,

The ghostly gas lamps fail at twenty feet.

Here, though the world explode, these two survive,

And it is always eighteen ninety-five.

Comments