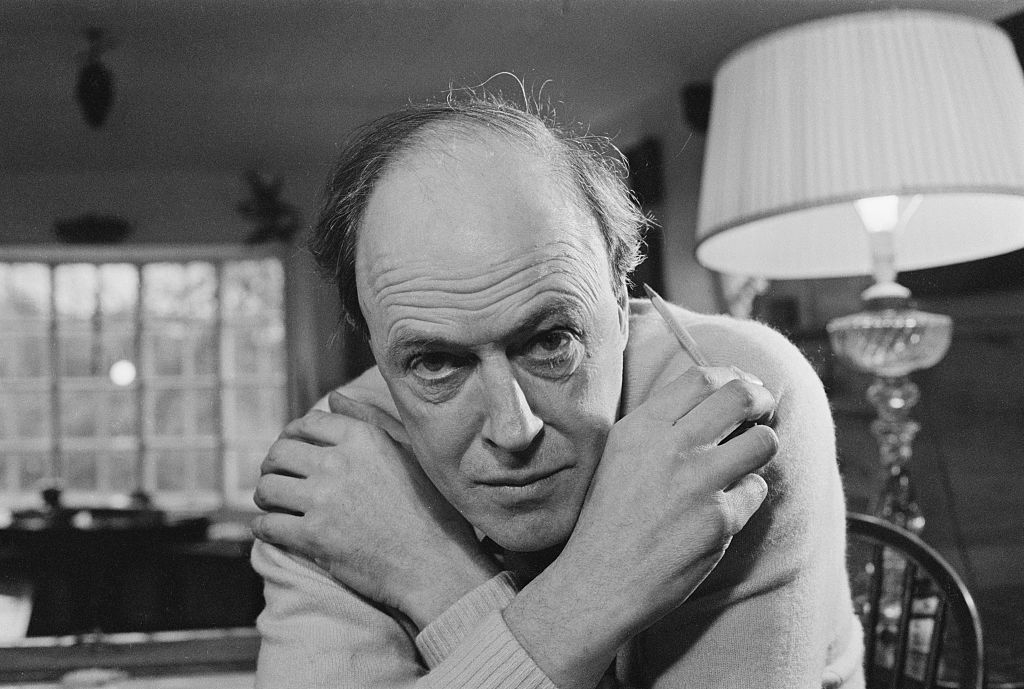

Roald Dahl Goes Woke: Part Two in what promises to be a very long and funny and ignominious series. Not three days after Puffin Books announced that they were to publish a series of specially commissioned new stories set in Roald Dahl’s fictional universes, a lead author of the continuation editions has had to issue a grovelling public apology.

The spirit of Roald Dahl has, like Elvis, left the building.

In a video message accompanying the announcement, the Radio One DJ Greg James, co-author of a Twits sequel to be called The Twits Next Door, had said that giving Mrs Twit a glass eye was a good way to help make the character more ‘disgusting’. Following complaints from the Royal National Institute of Blind People pointing out the value of ‘positive representation of disabilities in children’s books’ he took to social media to say: ‘we apologise unreservedly. It’s now gone. We understand that words matter and we pride ourselves on championing and welcoming everyone into the magical world of children’s books.’

The row causes further problems for a publishing project that was already meeting with a distinctly mixed reception. With a DJ and a newsreader as co-writers of the new Twits, and a celebrity-heavy roster contributing to a seasonal story anthology called Charlie and the Christmas Factory, not a few flinty-hearted onlookers were concluding that the magic of storytelling is taking a back seat to the magic of marketing.

That said, it’s not to be dismissed out of hand, this idea that children’s writers of today should be encouraged to take on the characters and stories of the children’s writers of the past and extend those stories or play riffs on them. Yes, this particular instance looks less like artistic communion and more like a crass corporate money-grab from a Netflix-owned company for whom stories are ‘content’ and characters are ‘IP’ and the former is to be ‘provided’ and the latter ‘leveraged’.

But taking old stories and extending or reimagining them is what literature in general has always done, and children’s literature in particular. In our own age, the great Jacqueline Wilson has extended the work of E. Nesbit and Enid Blyton, and I for one am dying to read the Narnia sequel that Francis Spufford has written but not published.

Children’s stories remain close in their bones to the myths and folktales which are the original forms of storytelling; and the defining characteristic of those forms is how available they are to retelling. The best and most enduring children’s stories are often those whose characters burst free of the stories in which they appear and seem to belong to the universe. Peter Pan, Mr Toad, the Mad Hatter, Mowgli, Aslan, Mary Poppins, William Brown: they are (as was said of Peter Pan) ‘immortal by election’. You could say the same of many of Roald Dahl’s characters: Willy Wonka, Matilda, the BFG, the Twits, Mr Fox…

So there’s no reason, at least on artistic principle, that these new stories set in the Dahlverse should not be given a fair hearing. It does not necessarily profane the existing stories to have new ones set alongside them, any more than Disney’s enjoyable but very different Jungle Book does harm to Kipling’s original. As James Joyce with Homer, Jean Rhys with Charlotte Bronte, and Salman Rushdie with Cervantes, so it may plausibly be with Konnie Huq and Roald Dahl.

They are apologising for something that is, for better or worse, quintessentially in the spirit of Dahl.

The Roald Dahl Story Company’s Director of Publishing Harriet Murphy certainly seems to think so. She told the Bookseller: ‘We have been so impressed by the authors’ brilliant ability to capture the unique spirit of a Roald Dahl story and bring us some wonderfully funny tales of their own imagination.’

But there, you see, is the rub. The ‘spirit’ of Roald Dahl is the one thing that 21st century publishing will struggle to accommodate. His books are, as the recent controversy over revised editions highlighted, stuffed with ageism, sexism, fat-shaming, lookism and pogonophobia. These aren’t incidental features, easily detached. They go through his work like jam through semolina. Dahl’s special genius was to tap into the cruelty, as well as the wonder, of childhood. There’s a lot of sadism in those books: Dahl licenses it by supplying baddies (ugly, fat, weird baddies) for the sadism to be righteously directed towards.

The late Ursula K. Le Guin had his number. She complained that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory had made her daughter ‘quite nasty’. You could make the case that the nastiness of her daughter will have been cause rather than effect of her enjoyment of Dahl, but potayto potahto: the connection is there.

You can be fairly sure, anyway, that when Roald Dahl gave Mrs Twit a glass eye, and had her prank her husband by taking it out and putting it in the bottom of his tankard of breakfast beer, he was not intending to celebrate her diversity. Dahl’s view of the world is one in which disgust has the status of something like a moral intuition.

So that the presumptive heirs to Dahl are apologising fervently for suggesting that a glass eye might be one of the things that make Mrs Twit disgusting is funny. They are apologising for something that is, for better or worse, quintessentially in the spirit of Dahl.

These new productions may capture something of Dahl, and it’s the something Netflix is after: the brand recognition and the capacity to earn royalties. But the spirit? No. The spirit of Roald Dahl has, like Elvis, left the building. Might not be the worst thing in the world, either.

Comments