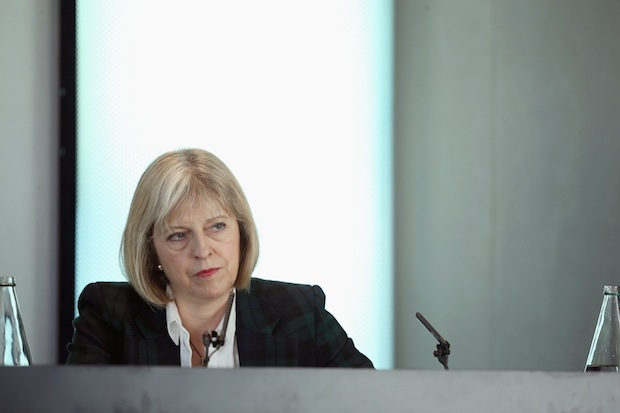

Theresa May will give a statement to the House of Commons this afternoon on the disappearance of terror suspect Mohammed Ahmed Mohammed. The Home Secretary has earned a formidable reputation over the past few years for emerging unscathed from a variety of Home Office rows, and Labour has struggled to lay a finger on her.

But this afternoon May will face a grilling from Yvette Cooper over the TPIM arrangements for Mohammed Ahmed Mohammed, and Labour wants to use this incident as a way of claiming that the Home Secretary’s own policy is flawed. Cooper said this morning that ‘given the long-standing concerns about the replacement of control orders, the limitations of TPIMs, and the pressures on monitoring and surveillance, the Home Secretary needs to provide rapid information about the extent and adequacy of the restrictions on Mohammed Ahmed Mohammed and ask the independent reviewer David Anderson to investigate urgently what has happened and the adequacy of the controls and powers in this case’.

Labour is asking two questions. The first is whether the TPIMs themselves are fundamentally flawed, which naturally Cooper wants to argue that they are. But the second is whether the specific TPIM notice in question wasn’t adequate. If that is the case, then it makes it much easier to stop this becoming a bigger row about whether the Home Office has damaged terrorism protection measures with a watered-down response to control orders.

This morning the Prime Minister’s official spokesman said that while the priority was to locate this suspect, ‘we need to look at whether there are lessons that we can learn from this’, but that the Prime Minister’s view of TPIMs hadn’t changed. The key for May will be to suggest that if there was anything wrong, it was with the specific arrangements, rather than the overall policy.

But there is something quite extraordinary about the way May survives these rows. She might not be very good at humour in the Chamber, but she is extraordinarily effective on so many other fronts, often to the frustration of those who work below her. Part of her success seems to be down to a desire to micro-manage and to freeze out anyone she doesn’t trust, which is better than letting them mess something up further down the line. I reported that Jeremy Browne was one such victim, immediately untrustworthy because he was a Lib Dem (even though civil servants in his previous department had initially assumed he was a Tory), and while it might frustrate the individual minister, May’s technique does mean she is on top of problems, rather than being hit in the face by a row she didn’t see coming. She is also adept at gathering backbench support and at listening to the worries of those MPs who don’t support her. This means that even when they rebel against something she is introducing, Tory MPs don’t turn on the Home Secretary herself. Many of them are very keen to support her today in just the same way.

This means that May has succeeded in taking the heat out of many of these inevitable Home Office disasters when they come along. Today we’re unlikely to hear anyone (bar John Mann or Dennis Skinner, who both love a good resignation call) calling for her to consider her position.

Comments