Something rather remarkable happened yesterday: Theresa May had a good day. This counts as news and is itself testament to the miserable time she has endured since she became Prime Minister. Some of this – much of it, in fact – was her own fault. Or at least her own responsibility. If she had called an election in September 2016 it seems likely she would have been rewarded with a handsome majority and, just as usefully, a thumping mandate for her own interpretation of Brexit.

Delaying until June 2017, however, meant she missed her chance. By that stage the moment had passed. The election became another unwanted imposition. Voters, given hefty encouragement by a disastrous Conservative campaign and May’s evident distaste for the fray, rebelled, biffing the government on the nose. From that moment, she was a hobbled prime minister.

And yet, despite it all, she is still there. And Boris Johnson is not. And nor is David Davis. The Daily Telegraph aside, the Tory press is, if not onside, then not in revolt either. Of course there is much countering, much feverish talk of betrayal and the possibility of a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister cannot be discounted. It may happen. But it looks – and this is a reminder of how quickly matters can turn – less likely than it did 24 hours ago.

Things are a little clearer now. You are with the Prime Minister or you are against her. For the time being, a greater portion of the Conservative party is with her than against her. A tipping point has not been reached. If Michael Gove were to resign that pivotal moment might arise but, at the time of writing, that looks unlikely too. Perhaps there will be a steady drip-drip of ministerial resignations that will, over time, make May’s position impossible but, right now, the Davis & Johnson affair seems more of a salutary warning about how to denude yourself of influence than a rallying call to fresh rebellion.

If you come at the Queen, you’d best not miss. At present, this storm seems less like the beginning of the end than akin to the moment, nearly a decade ago, when James Purnell resigned from the cabinet and it looked for a moment as though Gordon Brown might be toppled. Except he wasn’t, was he?

Some influential Tories certainly think the Purnell precedent a timely thing to remember now. Those ministers who remain in the cabinet are bound to the Prime Minister’s preferred interpretation of Brexit. Collective responsibility has – and not before time – been restored. If you stay in the cabinet now, you sink or swim with the Prime Minister.

And sinking her is not an attractive option. The frothier Brexiteers demand a Brexiteer prime minister. But who do they have in mind? And how could such a premier be installed without a general election? An election, it hardly needs to be said, that the Conservative party has little enthusiasm for. And even if they could sack the Prime Minister and replace her with someone more sympathetic to their thirst for a more violent Brexit what, precisely, would be their plan? And how would they have time to implement it? And then, having implemented it, how would they get it through the House of Commons? They have no compelling answers to any of these questions.

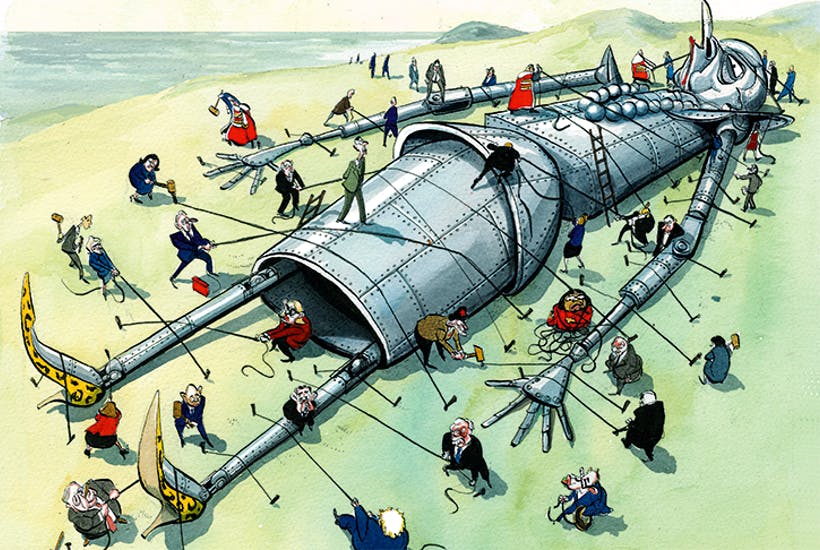

Which is why they are, for the moment anyway, beached. At long last, there is a measure of clarity. Theresa May’s Brexit may be imperfect and substandard and depressing in many ways but it is also, for now, the only Brexit in town. So a classic question arises: would you rather have half a loaf or risk having no loaf at all?

Boris is bust. David Davis is not going to be prime minister either. Jacob Rees-Mogg? Come on and come off it.

Meanwhile, as the likes of Hugo Rifkind and Stephen Bush have observed, May now has a story she can tell about Brexit. It might not be a very good tale but it’s clearer than any alternative the Brexiteers or the Labour party can offer. There is, mirabile dictu and only two years after the referendum vote, a government policy. It might even be a plan and a poor plan might be better than no plan.

The Prime Minister, then, is making a virtue of her weakness. May might seem an unconvincing or unlikely judoka but there we have it. If the Chequers summit was, as David Davis has described it, an “ambush” you wonder how a military man such as he failed to see it coming. By his own tacit admission, the Prime Minister prevailed, wiping out much of the cabinet’s opposition to her proposals.

Which is why, for now, it seems entirely reasonable to suppose that she is in a stronger position than she was just a few days ago. Her surviving enemies are out in the open, too, where they may be seen and their own strength more easily ascertained.

British politics has been so febrile for so long that we should no longer be so very surprised when surprising things happen. It may be surprising that Theresa May has had a good day and even a good week but there we have it. Truly, we live in an age of wonders.

Comments