‘This was Parliament at its best’, so went the inane and factually incorrect mantra of Kim Leadbeater as her Assisted Dying Bill made its way through the House of Commons. It did so on the back of intense duplicity about its safeguards by its sponsors and by the simple fact that the vast majority of MPs are intellectually unimpressive and suckers for anecdote over evidence.

The House of Lords was always going to be trickier ground for this Bill

The House of Lords was always going to be trickier ground. Their Lordships have their failings but they are less likely to be moved by the highly manipulative campaigns from pressure groups which have accompanied the bill. Many of them actually do know about medicine, the law and the plight of the sick and disabled, which is more than can be said for some of our parliamentarians.

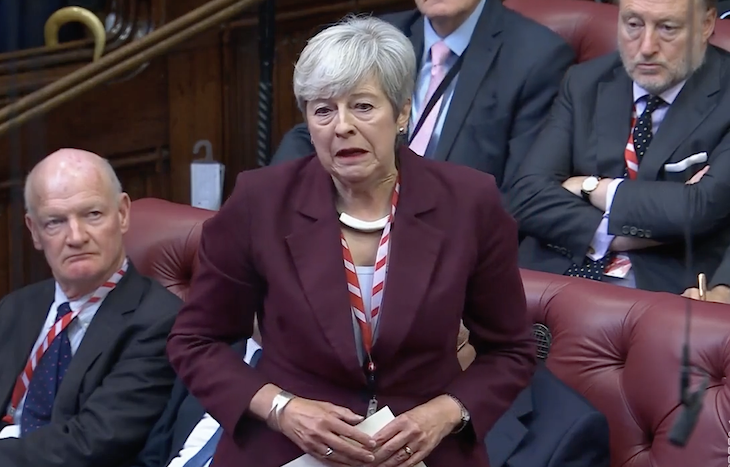

There were some truly phenomenal speeches. One of the best came from a most unlikely place: Theresa May. The former prime minister’s contribution was short. The Bill threatened, she said, ‘to reinforce the dangerous idea that some lives are more worth living than others.’ She then turned on the incredible linguistic obfuscation that has characterised its passage through Parliament: ‘this is not an assisted dying bill, it is an assisted suicide bill’. It was insanely hypocritical for society to claim it thought suicide was a thing worth preventing for the healthy and fit, while saying it was a moral good for those considered a burden.

Another unlikely highlight was the Bishop of London, who normally sounds like she’s announcing a rail replacement bus service. The choice offered by the bill she said, ‘was an illusion’ given the failure to listen to healthcare professionals, to explain how it would be integrated into a struggling health service and without any provision for improvements to palliative care.

Baroness Monckton spoke powerfully of the bill’s dangers to adults with learning disabilities, including her daughter, whose Down’s Syndrome leaves her ‘highly suggestible’ to influence from authority figures. The Baroness told the House that the ghouls at euthanasia lobbying group My Death, My Decision had even urged peers to reject amendments that might give relatives any input or even notify them. ‘What a strange view of the very nature of what a family is.’ This isn’t the first time the death lobby have tried to reframe the natural human instinct of trying to talk a loved one out of suicide as morally suspect, but that doesn’t make it any less shocking.

If I were Leadbeater or Falconer listening today, I’d be worried

Alongside the high quality there were, of course, the string of anecdotes and emotional manipulation which we have come, depressingly, to expect from the bill’s principle agitators. Baroness Grey Thompson – who is actually disabled, unlike those who claim to speak on behalf of them – begged their Lordships to remember that ‘good laws are not made from hard cases’.

Lord McColl, a 92-year-old retired surgeon who had previously worked with the founder of the UK hospice movement Dame Cicely Saunders, went a step further. He reminded their Lordship’s House that ‘anecdote comes from the Greek for ‘unpublished’ and ‘unpublished ought to be what most anecdotes remain.’ Alas these requests fell on deaf ears.

It has not been a good week for the ghoulish remnants of the Blair administration but that didn’t stop bill sponsor Lord Falconer from peppering his speech with startling mendacity about the Upper Chamber’s constitutional role. ‘Do what I say or else’ was more or less his line. Given that was how he vandalised the constitution during his regrettable tenure as Lord Chancellor it shows that, as with Mandy, Blairite leopards do not change their spots.

There were more shades of the Blair years from Margaret Hodge who told the house that ‘we should proudly be the standard bearers for this important societal change’. Yes! Onward privileged boomers, to the sunlit uplands free of the disabled and sick! That these people are incapable of seeing the obvious parallels for their creepy Utopian language in history is nothing short of terrifying.

Some weren’t quite so terrifyingly Utopian, just monstrously selfish. ‘I want to talk about MYself. MY rights. MY autonomy,’ droned Baroness Featherstone, speaking immediately after the disabled Baroness Grey Thompson. That’s right Lynne – you get in there and make it all about you. Lord Cashman scoffed and shook his head throughout Baroness Ritchie of Downpatrick’s remarks about the absence of proper palliative care in the NHS.

Baroness Hunter of Auchenreoch rehearsed – in the classically unfeeling timbre of someone who had been a PR advisor to, you guessed it, Tony Blair – the experience of someone she knew who had been ill. She pronounced the words ‘wheelchair-bound’ with the practiced air of a professional apparatchik. You got the sense from some of those peers that, for all their appeals to dignity, they didn’t really think the sick, ill or disabled were fully ‘people’ at all.

There were disappointments in the midst of the speeches: Lord Roberts of Belgravia may purport to be a Tory historian but he put forward a reading of history so drippingly Whiggish that it would have made even Gibbon blush. Apparently, it was necessary to pass the bill because of the great forces of progress. ‘Future generations will judge us,’ he cried. Yes, my Lord, they absolutely will.

Still, the overall quality was markedly higher than the Commons, with considerably more detail, erudition and forensic examination going on in their Lordships’ speeches and questions. So much Commons business depends on whips and patronage: the government protested neutrality on this bill but anyone with eyes to see realised long ago that the porcine fingers of the PM are all over it. One of the ways doubting Labour MPs were enticed into the ‘yes’ lobby was by being reminded of Keir Starmer’s own strong pro-views. No such carrots or sticks exist in the Lords. Far more than the Commons, the way the House votes depends on its mood, its feeling and the quality of the debate. As the day went on, more and more impressive speeches were made against than for, and the ‘hear hears’ became more pronounced in that direction. If I were Leadbeater or Falconer listening today, I’d be worried.

Comments