James Forsyth reviews the week in politics

You wouldn’t know it from listening to the Prime Minister, but the coalition is on course to be a great reforming administration. In its first 11 weeks, it has announced plans to reform all four major public services. At the same time, its first Budget mandated the largest public spending cuts since the creation of the modern welfare state: a shrinking which goes beyond anything Margaret Thatcher ever attempted. But to achieve its reforming ambitions, the coalition must work out how to steer past the reefs on which past reformers have been wrecked.

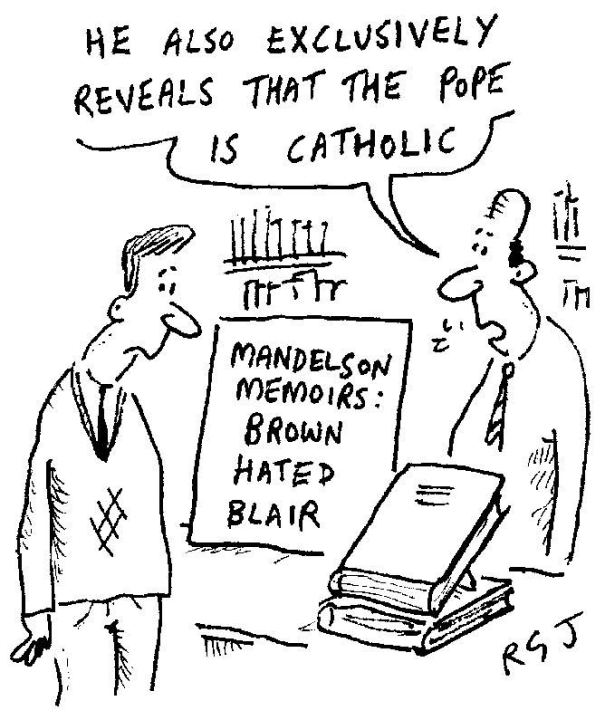

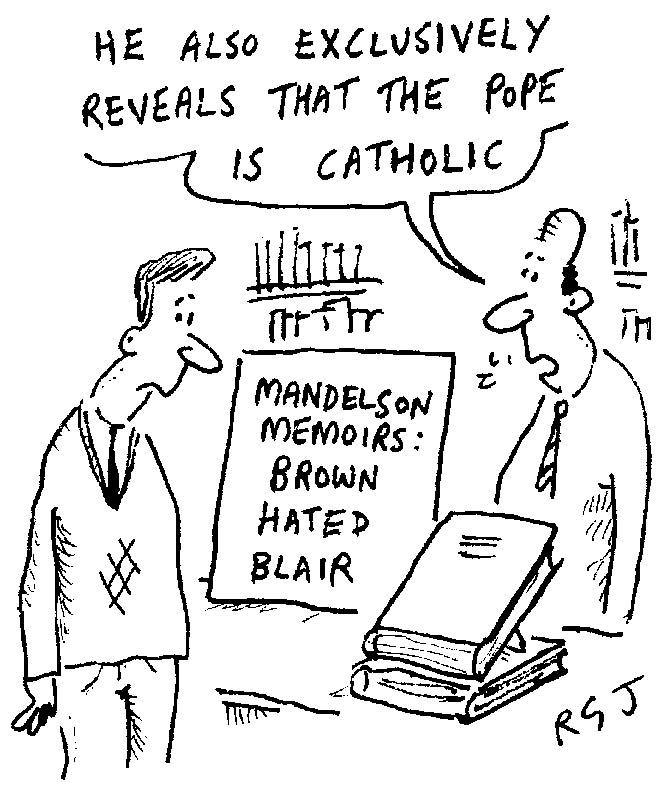

Tony Blair was so passionate about reform that speeches on the subject used to bring him out in a sweat. Lord Mandelson recalls in his memoirs how Blair had been warned before the 2005 election that the intensity of his ‘evangelical passion’ for reform was scaring voters. David Cameron, by contrast, appears to be barely aware of his government’s radicalism. When at Prime Minister’s Questions last week he was asked by one of his backbenchers about parents who had been waiting years for a new school to open, he noticeably failed to mention one of his government’s signature initiatives: the right of parents to set up their own state-funded schools.

Yet Cameron still has a better chance of delivering reform than Blair did. The need to make 25 per cent cuts in most departmental budgets means that the status quo — that great enemy of reform — is no longer an option. Blair might have had the passion for reform but Cameron has the moment for it, and that’s what matters.

But if Cameron is to be a successful reformer, he must learn the lessons of Blair’s failure. A few weeks ago the permatanned former Prime Minister made a rare public appearance in London. His purpose was to talk about the lessons he had learnt from his time in office. His intended audience was, clearly, the new government. The message hit its mark. Reforming ministers have read and re-read the transcript of his remarks.

Blair’s main warning was about the dangers of inertia. It is, sadly, still true that the British government has the engine of a lawnmower and the breaks of a Rolls-Royce. The Civil Service believes it is there to manage things not to change them. As Blair argued, reform needs to be driven through by a ‘tightly knit conspiracy of like-minded individuals’. But the Conservatives’ shortsighted decision to cut the number of special advisers has made this that much harder. For the sake of a few headlines about cutting the cost of politics, they have endangered their ability to deliver as a government. Special advisers are seen, in 1066 and All That terms, as a ‘bad thing’. But they are actually the people who ensure that the bureaucracy does what the elected official wants.

The decision to reduce the number of special advisers has left ministers even more isolated than usual. As one special adviser lamented to me recently, his minister has seven new policies he wants to push through. But the Civil Service isn’t particularly keen on any of them. So any day he spends working on one policy is a day that nothing happens on the other six.

If the greatest threat to reform is the Civil Service, the next is departmental turf wars. Take the emerging struggle over welfare. Iain Duncan Smith has predicated his reform agenda on making sure that people are always substantially better off if they move from welfare to work. But the Treasury has told Duncan Smith that he will have to find the money to make work pay from within his own budget and still deliver huge savings overall.

In response, Duncan Smith has proposed cutting various bits of middle-class welfare. But the Treasury is against such a move. This is shaping up to be a defining argument — but one in which Duncan Smith has found an unlikely ally. Nick Clegg is, like the US cavalry, arriving just in time, arguing that there’s no point going through the agony of welfare reform only to create a system as messy as the old one.

Clegg’s intervention is an example of how coalition politics is strengthening the hand of the radicals within it. Aside from the fiscal imperative, the reformers in the coalition have one great advantage over those in the last government: they hold the balance of power in Cabinet.

During the Blair years, the reformers of British politics used to lament how, for historical reasons, they were spread across the three main parties. Tory modernisers, right-leaning Liberal Democrats and Blairites were united by a common analysis but divided by tribal boundaries. They used to sit at dinner parties, inveighing against their shared enemies — statist Brownites, patrician Tories and limp Lib Dems — and imagining how powerful a united Reform Party would be.

The coalition has, almost, achieved this dream. It has yoked Tory modernisers together with Liberal Democrat Orange Bookers to pick up where the Blairites left off. When I asked one Tory spin doctor to explain their planned changes to the National Health Service, I was told that they were simply ‘better Blairisim’.

Michael Gove’s Academies Bill is an example of how the reformers are making up for lost time. It is explicitly based on Tony Blair’s education white paper, a document that had to be heavily diluted to appease the Labour party’s statist Brownite wing.

In opposition, both the Liberal Democrats and the Tories picked up the ideas in the white paper and ran with them. As a result, the Academies Bill can proceed in its intended form under the Tory–Liberal Democrat coalition. Indeed, when some Liberal Democrat peers were considering putting down amendments to it, it was Lord Adonis — Blair’s education minister — who intervened to persuade them to let the Bill be.

Still, you will not hear the government boasting of its radicalism. It is acutely conscious that many of its reforms will simply mitigate the consequences of the coming spending cuts. Take police reform. Its plan for directly elected police commissioners would bring about extraordinary change, making the police respond to the priorities of the public not the bureaucracy. This will end the scandalous situation where only one in ten police officers are on the beat at any one time. But its impact will be blunted by what is likely to be a cut of some 25 per cent to the Home Office budget.

The current situation is the best opportunity the reformers are ever likely to have. Let us hope that even without covering fire from special advisers, they have the courage to fight on, past the vested interests that stand in their way.

Comments