We would not want to return to the days when the transport secretary was actively engaged in the running of the railways, down to what the last wheel-tapper was paid. Nevertheless, Patrick McLoughlin’s answer when invited to condemn the £5 million bonuses which could be on offer to Network Rail directors over the next three years is a depressing comment on everything that is wrong with the railway industry. ‘It is not something I have interfered with because it is a private company,’ he said.

Network Rail is a private company of sorts, but it is one which is 100 per cent owned by the taxpayer. If the Transport Secretary is not prepared to speak up on behalf of its 60 million shareholders, then who is? The company exists in a kind of limbo, free from accountability and responsibility. It need fear neither the wrath of Mr McLoughlin nor of its customers, who have no choice in whether to use its services because there is no competition. If you want to take a mainline train in Britain, like it or lump it, you are going to have to hand over money, indirectly, to Network Rail.

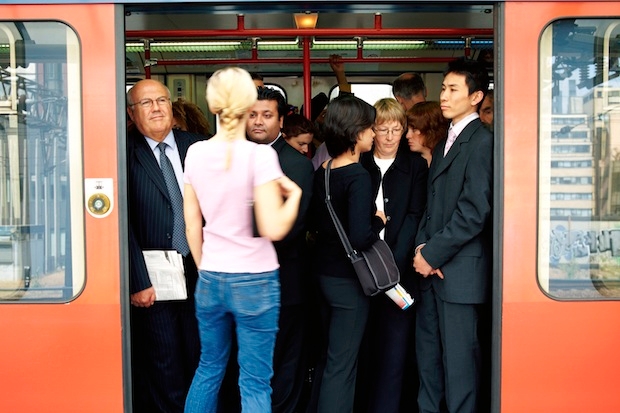

Nor, with the exception of a few towns fortunate enough to be served by more than one line, do passengers have any choice when it comes to choosing their train operating company. This goes a long way to explaining why commuters next January will face average fare rises of 4.1 per cent, with some fares rising by 9 per cent — and this for a service which will in many cases involve week after week of delays and overcrowding.

The experience of the rail industry in the nearly two decades since privatisation proves something which should have been obvious: private monopolies are no better than state-owned ones. No one should mourn British Rail: it was a turgid organisation, devoid of initiative and beset by bolshy industrial relations. Its managers ran it with one intent: to manage its decline. Passenger numbers fell steadily until the point of privatisation — when, in an early spurt of businesslike -thinking, rail companies began to come up with ways to attract passengers rather than simply cope with them.

But that early entrepreneurial spirit has not been sustained. Fares have been hiked up by rail companies which enjoy localised monopolies, and a brief flurry of new services appearing has come to an end. The only time the companies have to compete with one another is once every few years, when their franchises come up for renewal. But even then they do not need to sell themselves to the wider public — only to a team of civil servants. Fares are determined not by market forces but by negotiation with bureaucrats (in the case of regulated season tickets and saver tickets) or by how cheekily they believe they can exploit their monopolies (in the case of unregulated ordinary tickets).

There is no need for the rail industry to exist without competition. Last year two companies, First and Virgin Trains, fought bitterly for the right to run trains on the West Coast Main Line. The battle ended in recriminations and remains unresolved. But is there not a simple solution: to allow both companies to operate trains along the route, forcing them to compete with each other?

As for Network Rail, putting the entire rail network into the hands of one company which seems to be accountable to nobody makes no sense. If rail lines cannot be divided in such a way that obliges the operators of different lines to compete for business, then they should be owned by a public body which is accountable to the Transport Secretary, and for which he cannot escape responsibility.

For nation or party

Public spiritedness is awfully quaint these days. On Tuesday, reporters were mystified by the news that the late Ms Joan L.B. Edwards, a woman with no known interest in politics, had left £519, 000 to ‘whoever was the party of government of the day’.

In a time when everybody is either apathetic about politics or partisan, the thought that an old lady might want to support the governing party of the day seems crazy to modern commentators. The next day, a newspaper claimed that Ms Edwards’s will had in fact asked that her estate be given to the ‘government of the day’ and that coalition politicians had ‘pocketed’ the funds. Others said that her solicitors must have made a mistake.

As The Spectator went to press, the row over Ms Edwards’s money was still raging. It says something about the state of public debate that a generous and patriotic act has been met with first astonishment, then controversy; a gift that was supposed to benefit the government has instead been used to abuse it. Perhaps Ms Edwards wanted to support the nation, perhaps she really did want to support the party in power when she died — it’s a matter of interpretation.

What’s certain is that Ms Edwards wasn’t after influence or ermine. She just wanted to help. But it’s sad that, even if her half-million pounds ended up in the public purse, it would be eaten up by the public debt in less than three minutes. So RIP, Ms Edwards. Your generosity may be wasted, but it should not be forgotten.

Comments