GDP growth figures have become the barometer of choice for commentators trying to tell the political weather – a good measure of how the public will eventually fall in the faceoff between Osborne and Balls. The story goes that a return to sustained growth will mean a return to rising living standards. That means a vindication of the government’s position, and a victory for the Chancellor.

As a simple story, that makes sense if the pressures now facing Britain’s households are straightforwardly growth-related – if, in other words, we’re in a post-recession hangover that will vanish when growth returns.

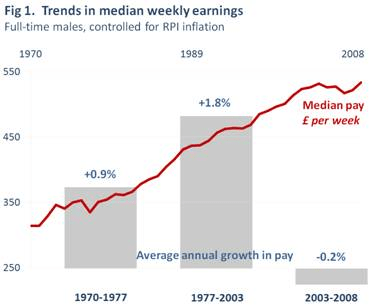

But there’s now mounting evidence of a deeper problem for living standards in the UK economy. Take the chart below. It shows long-term trends in UK median wages. It reveals that stagnant wages didn’t start with the 2008-09 recession, but began as far back as 2003, when GDP growth was still strong.

On its own, that undermines the simple assumption that a return to sustained growth will mean a return to rising living standards. And stood alongside Figure 2, it raises a bigger set of questions.

Fig 2. looks at long-term wage trends in the US context, and sets these alongside trends in US GDP per capita. It shows that middle incomes in the US have now been stagnant for a generation, even

while GDP has been strong. More precisely though, it shows that in the post-war period, US GDP growth tracked growth in living standards closely, but from the early 1970s, something changed.

From 1973 to 2010, US GDP more than doubled while the incomes of the bottom 90 percent of workers rose by just 10 percent.

That’s not to say the UK is now headed for 30 years of flat wages. Our labour market differs in many ways from America’s, and in any case it’s far too early to tell. But evidence

does suggest that the UK’s post-2003 wage slowdown has meant a similar ‘decoupling’ of wages from trends in output. Figure 3 captures that trend clearly. It shows a marked

divergence of growth in wages and growth in labour productivity from the early 2000s. In other words, the economy was still showing signs of good health at a national level, but from the vantage

point of households, things felt feeling decidedly queasy.

Of course, none of that suggests growth isn’t important. We won’t see a return to rising living standards while the economy remains stagnant. But it does suggest the story is more

complicated. Growth alone is unlikely to be enough.

James Plunkett is Secretary to the Commission on Living Standards, a wide-ranging investigation into the long-term economic trends hitting low-to-middle earners. The Commission is launched today by the Resolution Foundation.

Comments