The Welsh composer William Mathias died in 1992, aged 57. I was a teenager at the time, and the loss felt personal as well as premature. Not that I knew him; and nor was he regarded – in the era of Birtwistle and Tippett – as one of the A-list British composers (John Drummond, the Proms controller of the day, was particularly snobbish about Welsh music). But Mathias was a composer whose music I had played; whose music, indeed, me and my peers actually could play. His Serenade was a youth orchestra staple. It felt good to know that its creator was alive and well and working in Bangor, and when he wrote his Third Symphony I listened to the première in my bedroom, live on Radio Three. Like I say, it felt personal.

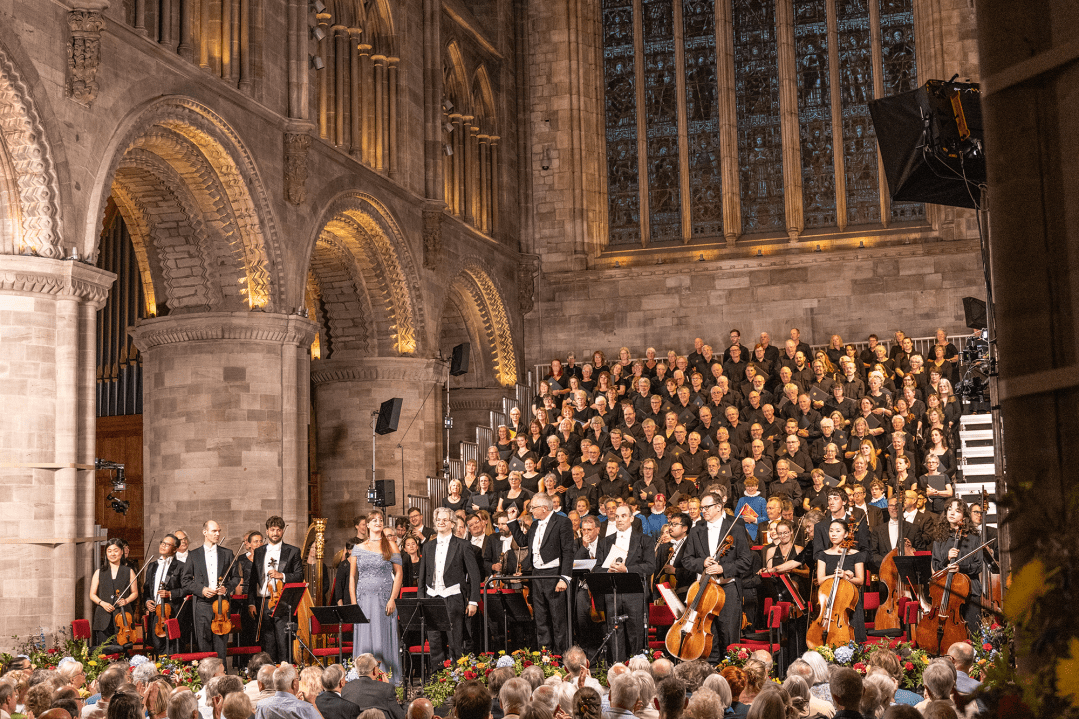

The 2025 Three Choirs Festival devoted its opening concert to Mathias’s 1974 choral symphony This Worlde’s Joie, and it was satisfying to hear his voice again. If you haven’t had the memo, the Three Choirs is now the premier festival for major British choral works that have slipped through the cracks of history. Stanford’s Stabat Mater, Bliss’s Morning Heroes, Elgar’s King Olaf: I’ve heard them all in one of those three great cathedrals. This year the Festival is in Hereford, which is specially enjoyable because the performers sit at the west end of the nave, so the evening light streams in behind the chorus. The 2025 programme includes Bliss’s Mary of Magdala, Howells’s Hymnus Paradisi and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s The Atonement. Intrigued? Watch this space.

But Mathias was in pole position. A spray of bells and tuned percussion opens This Worlde’s Joie, and the harmonies have the brisk, open sort of freshness you get after a thunderstorm. There’s a full chorus, a children’s choir (the Hereford choristers, nailing some particularly exposed writing) and a dark, jewelled orchestra (the Philharmonia). The opening gesture returns throughout the work’s four movements, which trace the seasons of human life from spring to winter through the medium of medieval English poetry. You’d lose your Arts Council of Wales grant for that, these days.

Regardless, Mathias has nothing to prove, and nor does his music. This Worlde’s Joie wears its debt to Britten’s Spring Symphony without apology, then throws it off just as blithely when Mathias finds he has something very different to say. The Festival went all-in, as it usually does with these rarities, and the soprano soloist Eleanor Dennis gave a mischievous smile as she pealed out a string of mildly suggestive verses by the Tudor poet Robert Greene (the Upstart Crow chap). By then we were in the ‘Summer’ section. Mathias flooded the orchestra and chorus with hopeful, sensuous harmonies – music that showed the Festival Chorus (amateur singers, like most large choruses in the UK) at its most radiant.

In a tradition dating back to the 18th century, it was conducted by the Cathedral’s own MD Geraint Bowen, who seemed well on top of things – as he had been before the interval, in Dvorak’s Te Deum. Czech music at this tweediest of English festivals? Careful, your preconceptions are showing. Dvorak conducted at the Festival in the 19th century, Saint-Saëns and Kodaly were regulars and Sibelius’s deeply weird Luonnotar was a Three Choirs commission. The Te Deum glowed, even if Dvorak’s dancing cross-rhythms couldn’t really survive the cathedral acoustic. That’s the trade-off for performing in a venue like this, and perhaps it’s a price worth paying for the sense of musical community that animates the whole Festival. Great beer tent, too.

Arnold’s Fifth is arguably the finest British symphony since Vaughan Williams

Over in Gloucestershire, another Midlands festival celebrated its 80th anniversary. For a decade or so after the second world war the Cheltenham Music Festival looked like the future of British music, lending its name to a whole sub-genre of bracing, sturdily-wrought symphonies by the likes of Rubbra and Alan Rawsthorne. Then the 1960s happened. According to anecdote, during the première of Malcolm Arnold’s Fifth Symphony in 1961 critics started leaving the hall to phone in their slatings while the music was still in progress.

Well, bully for them, because Arnold’s Fifth – a hallucinatory, primary-coloured song of anguish and euphoria – is now the last ‘Cheltenham Symphony’ standing, and arguably the finest British symphony since Vaughan Williams. The Festival brought it back to its birthplace in a muscular performance from Gergely Madaras and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, whose horn section sounded particularly ripped in the confined space of the Town Hall. The Cheltenham Festival has fallen on lean times of late; it’s difficult to imagine them premièring a symphony again any time soon. But they did commission an anniversary fanfare from the young composer Anna Semple, which (unusually for this sort of commission) had something to say, and said it with imagination and assurance in exactly as many notes as it required.

Comments