Blistering barnacles! Thundering typhoons! What dastardly double-dealing! To bolster their puny team of pen-pushing, quota-quoting civil servants, those fiendish Brussels bureaucrats have recruited Europe’s greatest investigative reporter. With Tintin on the EU’s side in the forthcoming Brexit negotiations, do our valiant Brexiteers stand any chance at all?

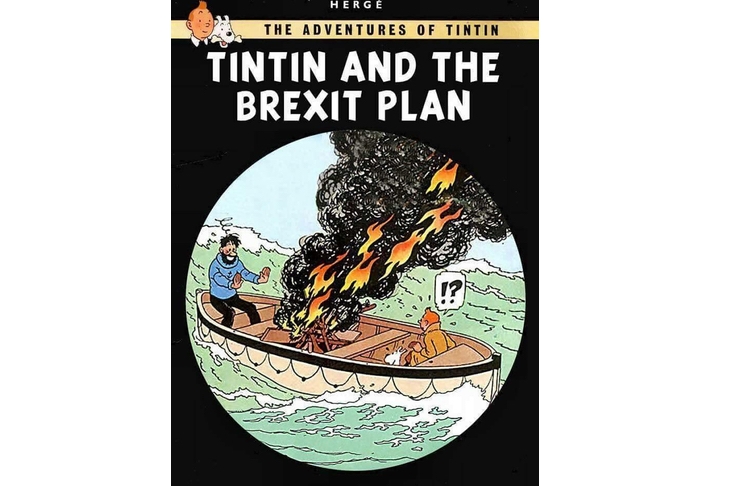

No idea what I’m on about? Then let me explain. As the Daily Telegraph has revealed, the European Council’s Brexit task force has enlisted Tintin as their cheerleader, by hanging a poster of the intrepid journalist in their Brussels war room. This poster is a mock-up of a new Tintin book called Tintin and the Brexit Plan. The picture shows Tintin and Captain Haddock on a stormy sea in a small lifeboat, upon which a drunken Haddock has made a bonfire of the oars, in order to keep warm.

The title is pure fiction, of course, but avid Tintinologists will instantly recognise the illustration as genuine. For anyone who wants to know (and for anyone who doesn’t, for that matter) it’s the final frame on page 19 of Captain Haddock’s first adventure, The Crab with the Golden Claws. In this gripping thriller, which announced the advent of Hergé’s mature style, Tintin and Haddock are cast adrift, after Tintin reveals to Haddock that his crew are smuggling opium in tins of crab meat.

So, what does this tell us about the EU mindset? And is it fair to align Tintin to the EU cause? As any self-respecting Tintin fan knows full well, Hergé was no stranger to European politics, and many of his finest stories are intensely political affairs. Yet although he lived until 1983, by which time the Common Market had already morphed into the European Community, Hergé studiously avoided any mention of the EC. Does this mean he was a fanatical Europhile? Or a fanatical Europhobe? Who knows? Maybe it simply meant that, like a lot of Europeans (and an awful lot of Britons), he had no opinion about the subject whatsoever, and found the whole thing supremely boring.

Nevertheless, you can see why Europhiles would welcome Tintin as a mascot. He’s Belgian for a start, and most of his enemies are Americans (American big business comes in for a particularly rough ride – eat your heart out, Donald Trump). His pan-European career is a paradigm of freedom of movement. He’s relaxed about immigration, and breezes across European borders with a Schengenesque disdain for security checks or passport controls.

Captain Haddock, conversely, is the archetypal Little Englander (no, he’s not Scottish, despite his Scots accent in the Spielberg movie) which makes his role as the foolish fall-guy in this propaganda poster especially apt. He’s actually a pretty accurate personification of the way a lot of Continentals tend to see us, especially since Brexit: brave and loyal but hot-headed, with a fondness for romantic myths about our ancestry and a weakness for the bottle. Holed up in Marlinspike (modelled on the French Chateau de Cheverny) his home is his castle. He’s wary of outsiders and suspicious of foreigners (compare his attitude to gypsies with Tintin’s in The Castafiore Emerald).

However Europhiles should be wary of embracing Hergé too closely for, like the drunken Haddock, Tintin’s creator comes with a good deal of awkward baggage. He first drew Tintin for Le Petit Vingtième, the children’s section of a Catholic newspaper which would nowadays be called proto-Fascist. The man who ran it, Abbe Norbert Wallez, kept a portrait of Mussolini on his desk; its foreign correspondent, Leon Degrelle, subsequently became leader of Belgium’s Fascist party and a ‘friend’ of the SS. Hergé can hardly be blamed for this, of course, but neither does it make him the perfect poster boy for ‘ever closer union’.

The Crab with the Golden Claws was written during the German occupation of Belgium, when Hergé’s employer, Le Soir, came under the direct control of the Nazis. In Tintin’s subsequent adventure, The Shooting Star, the principal baddie was a scheming financier with a big nose called Bohlwinkel. It was an innocent mistake, and Hergé was later absolved of any blame, but it was an unfortunate coincidence nonetheless.

After the war, as an employee of the occupied press Hergé was banned from working until he finally obtained a ‘certificate of good citizenship’ in 1946. In the interim he was arrested several times, by the police and the resistance. This was terribly unfair (his prewar adventure King Ottokar’s Sceptre was a thinly veiled satire of the Nazis) and he eventually emerged without any stain upon his character, but the opprobrium, however unjustified, was sufficiently widespread for the Belgian newspaper La Patrie to run a spoof strip called The Adventures of Tintin & Snowy in the Land of the Nazis.

So, Tintin and the Brexit Plan is a perfect encapsulation of Brexit, albeit a bit more complex than the European Council might suppose. Watch this space for a reboot of The Castafiore Emerald with Theresa May as Bianca Castafiore, and Boris Johnson and David Davis as Thomson and Thompson.

Comments