There is a fine old tradition of distinguished literary men addressing their loved ones by animal-world pet names. Evelyn Waugh saluted Laura Herbert, the woman who became his second wife, as ‘Whiskers’. Philip Larkin’s letters to his long-term girlfriend Monica Jones are full of Beatrix Potter-style references to the scrumptious carrots that his ‘darling bun’ will have unloaded on her plate at their next meeting should wicked Mr McGregor not get there first. Wanting to soften the blow of his sacking by the BBC Third Programme in the early 1950s, John Lehmann went off on holiday with an intimate known to posterity as ‘the faun’. But none of this sentimentalising comes anywhere near in its effects to the torrent of effusiveness, personal mythologising and, it has to be said, downright archness uncorked by The Animals.

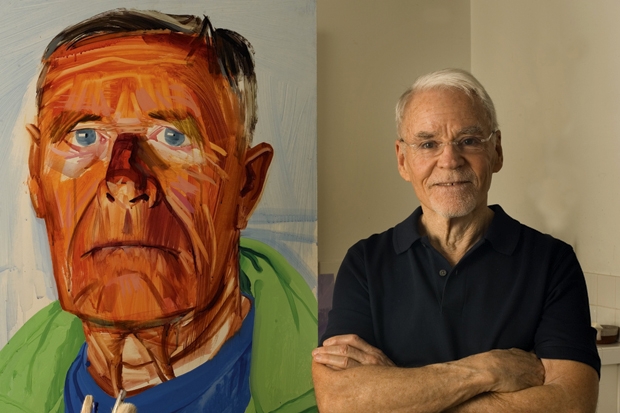

Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy met in California in February 1953 when Isherwood was in his mid-40s and Bachardy a stripling of 18. Their relationship endured — with intermissions — until Isherwood’s death in 1986, and first turned epistolary in 1956 when Isherwood, thinking the privations of his mother’s house in Cheshire too austere for an American tourist, left Barchardy behind in their London hotel. Later correspondence was prompted by Don’s absences, sometimes abroad but on occasion in New York, furthering his career as a professional portraitist; the most interesting date from a period in the 1960s when, armed with his boyfriend’s address book and a highly plausible manner, Don heads to London to study at the Slade while Christopher sits and frets in Santa Monica.

As for the nick-names adopted for these exchanges, Isherwood is ‘old Dobbin’, a sturdy and mostly indulgent carthorse, Barchardy ‘Kitty’, an affectionate but somewhat highly strung cat. Over the years these endearments undergo a certain amount of development (‘Dear Longed-for Colt … Dearest Catkin … Darling Nag … Darling Fur … Beloved Velvet Rump’) but the emotional patterning remains, and Katherine Bucknell, the duo’s resourceful editor, is keen to stress its therapeutic value. Isherwood, she explains in the course of a sympathetic introduction, ‘believed their animal personae had a mythic power that would keep the relationship alive’ by creating ‘a world, a safe and separate milieu’ in which the two, however detached by distance or temporary fracture, could jointly luxuriate.

There follows a terrific exercise in high-camp call and response. Old Dobbin doesn’t sleep so well, missing his tiny cat, Isherwood coyly insists, only to be told by return of post that Kitty ‘longs so to be back in my basket … It seems like ages since I left my horse.’ Naturally there occasional hints of anxiety (‘Dobbin is only happy if Kitty finds consolation — ONLY NOT TOO MUCH’) and the clouds of romantic glory are sometimes swept aside by Bucknell’s revelations about the various people each is having affairs with while the other’s back is turned, but the transparent sincerity of the tone has the vital effect of halting the reader’s instinctive response — to laugh out loud — in its tracks.

Well, nearly always (‘His dear letter and his precious story has just arrived, both smelling so deliciously of HORSE that Kitty’s nostrils are in a state of nervous excitement.’) Predictably, the social and indeed intellectual worlds on offer here, whether in the Californian pine woods or the dining-rooms of upper-bohemian London, are a version of that age-old high-class homosexual admixture of sleaze and sensibility in which the choicest observations about art and literature are brought down to earth by bitchiness and rats-in-a-sack sex lives. Less predictably, of the two correspondents pressing their observations on us, by far the more interesting is Bachardy.

Perhaps, in the end, this disparity is simply a question of milieu. Certainly Isherwood, back in California, has his swami (the interest in oriental religion is kept up throughout) and his dinners with such Hollywood notables as Danny Kaye and Marlon Brando. Barchardy, on the other hand, has the relish of the young thruster setting about his career, combines wide-eyed celebrity-spotting (‘Sybil and Richard Burton have let me have their house in Hampstead’) with shrewd accounts of meeting the English painter Keith Vaughan, drawing a drunken Henry Green and attending upon the ramshackle court of James Baldwin, while offering wayside vignettes and comments on Isherwood’s works in progress that you suspect his mentor was very glad to have.

There is, for example, a jaw-dropping account of his stay with a friend named Marguerite Lamkin in darkest Louisiana on the evening her father tries to kill himself (‘Don, something terrible has happened.’) As the night wears on and the old man, gravely injured by a gunshot wound to the temple, is taken away to hospital, Marguerite begins to immerse herself in the drama, remarking at one point of Susie, the family’s servant, that ‘You know she found a piece of skull on the floor.’ Isherwood, on receipt of this five-page tour de force, notes that he ‘enjoyed it so much that I quite forgot to feel sorry for anybody’.

No point in pretending that these despatches from a long-distance gay relationship will be to everybody’s taste, or even that the homosexuality has anything to do with it — archness is archness, whatever one’s sexual inclination — but there is an amusing game to be played in seeing if you can identify the very large number of famous and glamorous (and sometimes less famous and less glamorous) people mentioned only by their Christian names without reference to Bucknell’s herculean footnotes. I patted myself on the back for recognising ‘Cuthbert’ (the writer T.C. Worsley, author of Flannelled Fool) but came a serious cropper over Isherwood’s mention of a ‘dinner with Evelyn’. Evelyn Waugh? No, an American psychologist and psychotherapist named Evelyn Hooker. As for ‘Tito’, described as having developed ‘really quite crazy persecution delusions’, my money was Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia until Bucknell got in with a Mexican actor called Tito Renaldo, ‘intermittently a monk at the Vedanta Society’.

The Animals, an invaluable pendant to Katherine Bucknell’s four-volume edition of Isherwood’s Diaries, comes to a close in April 1970 (‘Darling Flufftail … Beloved Pinkpaws …Worshipped Plumed Steed’) with the stage version of Cabaret improving the finances and the film treatment in prospect. It is a fascinating sociological document while, like most exchanges between two people wrapped up in the tantalising subject of themselves and each other, lacking very much real interest in the wider world. To give one small but salient example of this tendency to self-absorption, I never did find out whether poor Mr Lamkin lived or died.

Comments