Sam Leith has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Salman Rushdie has long hated and struggled against the idea that the 1989 fatwa pronounced on him after the publication of The Satanic Verses should define his career or his life. It was, as he frequently pointed out, a book he published only a quarter of the way through his career. He wanted the life of a writer, and for his books – even ‘that book’ – to be read as books rather than as footnotes to an episode in his biography or tokens in some pre-digital culture wars.

Two nights before the reading, Rushdie dreamt he was attacked by a man with a spear in a Roman amphitheatre

He thought he had managed that. The only people who ever asked him about the fatwa, he told me when we met in 2020, were journalists: ‘to be dragged back into the late 1980s is boring.’ At the beginning of 2022, he was living an ordinary and very happy life in New York with his fifth wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths. He had just finished a new novel, Victory. He was, as he now preferred to be, close to anonymous: the tabloids no longer pursued him, and this unexpected and fulfilling late-life romance and marriage (about which he writes movingly) had gone, by design, almost unnoticed by the public. Then he went to give a reading in Chautauqua, upstate New York, and a young man rushed out of the audience with a knife and tried to kill him.

Looking back on the night before, Rushdie describes himself, happy in bed: ‘The future rushes at him while he sleeps. Except strangely, it’s really the past returning, my own past rushing at me […] The revenant past, seeking to drag me back in time.’ This murderous nonentity failed, just by a hair, to kill Rushdie – but he did make him, once again, the fatwa guy, ‘the guy who got knifed’.

Knife is the book Rushdie has written to try to wrest the narrative back: to ‘answer violence with art’. When he wrote Joseph Anton – his long-delayed, or perhaps I should say long-considered, reckoning with The Satanic Verses affair – he cast it in the third person, halfway to fiction. There was no long gestation with Knife, though, and none of that metafictional tricksiness. This, as he told David Remnick in the first interview after he was released from hospital, would be in the first person. This is an ‘I-book’: ‘when somebody wounds you 15 times it definitely feels very first-person.’

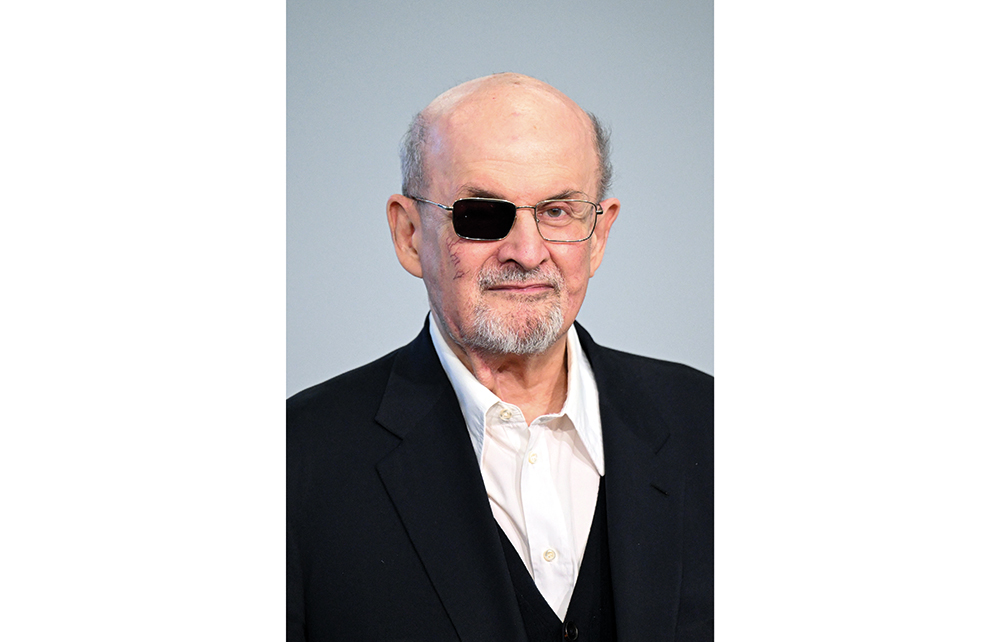

Knife describes Rushdie’s life before the attack, the attack itself (in gripping and terrifying detail), and the slow process of physical and mental recovery that followed. Rushdie lost an eye, almost lost the use of his left hand, had staples in his face and scars on his chest that, he boasted to his son, resembled the New York subway map. Pints of fluid were decanted from his abdomen. He offers wan words of advice: ‘If you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut… avoid it. It really, really hurts.’ ‘Dear reader, if you have never had a catheter inserted into your genital organ, do your very best to keep that record intact.’

The fact that he survived is routinely described as a miracle, and Rushdie sees it that way even as he disavows the notion. As he and Eliza (who is a film-maker and photographer as well as a poet) start to document his recovery for a yet-to-be-released film, he writes:

I […] wanted to think about miracles, and about the irruption of the miraculous into the life of someone who didn’t believe that the miraculous existed, but who nevertheless had spent a lifetime creating imaginary worlds in which it did.

Rushdie notes the spooky coincidences. He describes how two nights before the reading he had a nightmare in which he was being attacked by a man with a spear in a Roman amphitheatre – ‘It felt like a premonition (even though premonitions are things in which I don’t believe)’ – and had contemplated cancelling the event. He remembers looking at the moon in Chautauqua the evening before, and his mind roaming (in very Rushdiean fashion) between an Italo Calvino story, a Tex Avery cartoon and the 1902 short Le Voyage Dans la Lune, which includes an image of a rocket violently embedded in the moon’s right eye. He notices that Shalimar the Clown started with the image of a dead man and an assassin with a bloody knife; that there’s a scene of someone being blinded in Victory; that The Satanic Verses begins with the words ‘To be born again, first you have to die’.

So the narrative sections of Knife are told with reportorial directness; but the sensibility that animates them, and animates the essayistic reflections and digressions in the later part of the book, is that of Rushdie the novelist. Even as he hallucinated on morphine and fentanyl, his hallucinations were of fantastical architectures built of the letters of the alphabet. He’s a writer with a well-stocked mind who roams ad lib between high culture and pop culture, who likes jokes and ironies, who draws parallels, who is bold and direct in the defence of the value of art against ideology, and free speech against nobodies with knives.

Rushdie writes that he wanted to structure Knife around three figures: himself, Eliza, and the would-be killer, whom he denies his real name and prefers to call ‘The A’ (‘What I call him in the privacy of my home is my business’). Of A, who claimed to have read no more than a couple of pages of Rushdie’s work and decided to kill him after he thought he seemed ‘disingenuous’ in a YouTube video, he makes a novelist’s judgment: ‘My strongest feeling, after reading his remarks, was that his decision to kill me seemed undermotivated.’

The least effective part of this book, to my mind, is a longish section towards the end in which Rushdie confronts his would-be murderer in a series of imagined dialogues (he had blown hot and cold on whether he wanted to try to meet the real-life A in a courtroom). Rushdie imagines the arguments he’d mount and imagines, too, how little impact they would have on a mind so shallow and incurious. It has the slight feel of playing tennis without a net; or, perhaps, ping-pong with one half of the table tilted to the vertical. The banality of this particular evil is so obvious already, so manifest, there’s no getting a purchase on it with even a mind as spry and learned as Rushdie’s.

A is nothing, and what he stands for is nothing. The side Rushdie’s on, and which he writes about with real vigour and application, is the side of life, and of love: outstandingly the love he shares with Eliza, the second of the book’s miracles, but also with his grown-up sons and grandchildren and his many friends. The love he receives from the wider world, too, buoys him. He proudly reproduces the public tribute Joe Biden read at the White House, and it’s clear that the worldwide outpouring of affection for him after the stabbing has done something to alleviate his resentment of the distinctly patchy support he received when the 1989 fatwa turned his life upside down. If he’s now stereotyped as the ‘good Rushdie’ – ‘a sort of virtuous liberty-loving Barbie doll, Free-Expression Rushdie, then I will embrace that fate.’

There’s melancholy, though, even as he celebrates his return to health. In an especially piercing passage he describes his last meetings with the dying Martin Amis. He reflects on the friends and literary peers struck down at around the same time – Hanif Kureishi, scythed down in the same year by the damage from a fall in a hotel room; Paul Auster ill with cancer – and remembers Angela Carter, Naguib Mahfouz, Christopher Hitchens. Talking about Amis, it’s not literary glory he recalls with most longing but the poker games of 30 years before.

And as he told Eliza in the hospital: ‘No matter what I’ve already written or may now write, I’ll always be the guy who got knifed. The knife defines me. I’ll fight a battle against that, but I suspect I will lose.’ It cuts, you could say, both ways.

Comments