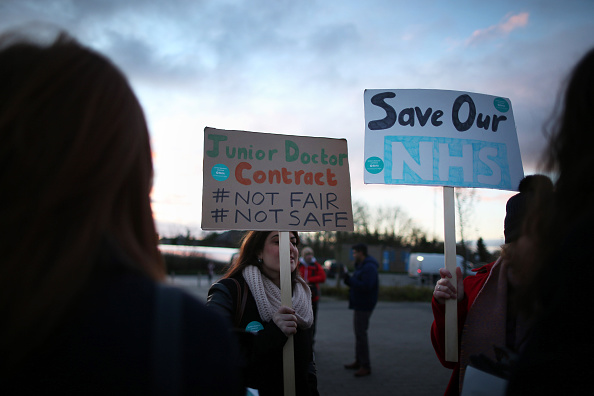

This is a bleak day for the NHS. The doctors strike has gone ahead and some 3,000 operations have been cancelled. Talks broke down last night, and the British Medical Association has shown it is quite prepared to put patients in the firing line in its dispute over a deal that would mean a pay rise, not a pay cut, for 99 per cent of doctors. From 8am this morning, only emergency care will be provided.

Treatment for that once-virulent condition, the British disease of strikes, has largely been successful. The number of working days lost to industrial action in the first ten months of last year was the second-lowest since records began. Pay and conditions have been relentlessly improving. Since the Winter of Discontent in 1979, the average worker’s disposable income has almost doubled. And no thanks to pressure from trade unions: the steady progress comes from the transformative effects of an open economy and a free market.

In the 1970s and early 1980, it was miners, steel workers, railwaymen, bin men, and British Leyland car workers who earned the worst reputations for trade union militancy. Striking was almost entirely associated with blue-collar workers standing around braziers in their donkey jackets.

Now things couldn’t be more different. Of the above groups, only railway workers retain a reputation for industrial action, and almost all strikes are carried out by privileged white-collar public sector staff. Almost half of the days lost to strikes in 2014 were in public-sector administration, with most of the others in education and in health and social care. With the junior doctors’ strike and a walkout by teachers in West Dumbartonshire, it is a trend which is sure to continue.

Professionals have grown more militant, but unions have not grown more professional. As with the union barons of yore, the British Medical Association first sought to spread misinformation. First, by publishing a fake ‘pay calculator’ which wrongly suggested that doctors’ pay would be cut by almost a third. Then the BMA put junior doctors in front of cameras to claim that they are going to suffer ‘longer hours and pay cuts’. It just isn’t true.

The new arrangements were always going to balance cuts to overtime pay with a healthy 11 per cent uplift in basic pay (now averaging £53,000 for all those not in the first two years of training). Three quarters of doctors were always going to be better off. Last November, however, the health secretary Jeremy Hunt made an improved offer, which guarantees no cuts to almost every doctor’s pay for three years. Only 1 per cent of doctors will lose out — the ones who work unhealthily long hours.

When the BMA sensed that public support for a strike was wearing thin, it did what the railway unions always do: pretended the dispute was about public safety. Yet the new deal improves safety; the maximum hours a week that any doctor will be allowed to work under the new system will fall from 91 to 72. The maximum number of consecutive night shifts which any doctor can work will fall from seven to four. Were the government proposing a longer working week, there might be a legitimate point about safety. As things stand, it’s a nonsense.

The old industries have shrunk, of course: miners and steelworkers no longer exist in large numbers. But that is far from the whole story. Some formerly militant unions have been forced into a new sense of realism because they are no longer feather-bedded in nationalised industries and can see what damage they would wreak by striking. Workers at the Grangemouth refinery pulled back from a strike in 2013 because they could see that the owner of the plant, Ineos, was serious about closing it down. After the crash, the industrial trades unions behaved sensibly and constructively — accepting pay restraint in return for fewer redundancies.

Car production in Britain is roaring: Nissan’s Sunderland factory alone makes more cars than the whole of Italy. Toyota has said it is so pleased with its plant in Derbyshire that it will stay regardless of whether or not Britain leaves the European Union. Indeed, you never hear now of car workers going on strike, because they are all employed by private companies with more professional relations between staff at all levels.

Most bin men, too, are now employed by outside contractors with whom they seem able to negotiate pay without constantly threatening to walk off the job. There aren’t many organisations that can still hold the public to ransom: the London Underground is one and the NHS is, alas, another.

But if doctors were employed by independent companies, each with its own contract with the NHS, they would have a huge disincentive to strike because they would know they were putting their firm’s contract — and their own employment — at risk.

Mr Hunt has made mistakes along the way: he placed too much weight on the idea that a seven-day NHS is needed to improve patient safety. But the biggest mistake is one made by David Cameron: to think he had kept the NHS safe by ringfencing its enormous budget and not attempting radical reform of the whole system. As the doctors strike clearly demonstrates, an unreformed NHS will always represent a risk to the government and patients alike.

Comments