Two words have been everywhere touted during this political season: ‘fairness’ and ‘equality’.

Two words have been everywhere touted during this political season: ‘fairness’ and ‘equality’. By the time you read this, after Wednesday’s comprehensive spending review, occurrences of the first will have reached epidemic proportions. Let us examine both.

Among Western nations an understanding has dawned that our long-established global economic preponderance is floundering; so we can afford less of the luxury of concern for the weakest in society, a drag on economic competitiveness. From the French revolution’s trio of goals, égalité is being quietly dropped. The left will not wholly forsake what has become for them an almost sacrosanct word, if not idea; so they are effecting a quiet shift from equality pure-and-simple, to ‘equality of opportunity’, which appears to mean that everyone should at least get an equal start.

As a useful guide to policy, ‘equal opportunity’ crumbles on inspection. At what stage in individuals’ lives should opportunity be equalised? At birth? Then how do we treat those who slip behind despite being helped to make a good start? How do you equalise a child’s opportunities without equalising its parents’ circumstances? How do you deal with unequal progress resulting from unequal talent? In the end, making ‘equality’ your goal can only mean levelling repeatedly, insistently, and throughout citizens’ lives. Unchecked, humans continuously get ahead or fall behind — then entrench advantages over others and try to transmit them to family and friends.

Liberals and the right have always understood this, and so are also wary not only of equality, but of untrammelled laissez-faire: because if society’s winners are given free rein to entrench their status they will try to stifle the very competition through which they achieved it; and liberals and the right see competition as a mainspring of progress.

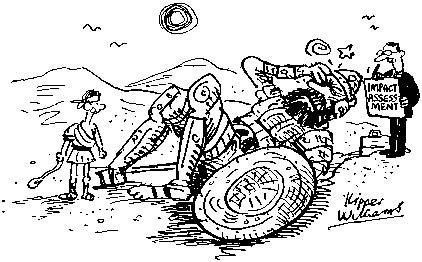

That is why ‘fairness’ is becoming so fashionable as a political ideal. It bespeaks a concern for the disadvantaged, but seems also to acknowledge the place of healthy competition in life: ‘fair’ competition, in which everyone is given a chance.

A chance. But how much of a chance? A bit of a chance? The same chance? And how do we treat those who fluff their chance? How do we help the children of those who fluff their chance? ‘Fairness’ does not answer the problems raised by ‘equality of opportunity’ as a policymaker’s goal: instead it sidesteps them through the use of a term that means, and has meant, sharply different things to different people down the ages. People all agree on the box labelled ‘fairness’ but may argue violently about its contents. This is both the strength and the weakness of the word: ‘fair’ is a hooray-word which leaves politicians a free hand in translating it into action.

Does the word ‘fair’, then, have any meaning at all? Does it offer any kind of encouragement or constraint? It does. ‘It isn’t fair!’ is almost the first complaint a toddler learns to make, and the infant plainly means something urgent and important by it.

What? Careful inspection of the wildly different contexts in which ‘fair’ and ‘unfair’ are used reveals that there are only two things people may reliably mean by calling an action ‘unfair’. First that it offends the rules; that it breaks an implicit or explicit agreement. Cheating at games is the quintessentially ‘unfair’ thing to do.

But can a rule itself be unfair? Yes, and this brings us to the second way the term may be used: all human beings have an idea of natural justice — against which justice in the legalistic sense may offend. On closer inspection, however, ‘natural justice’ really means little more than what we suppose to be our innate sense of right and wrong.

And it is into this thicket — what we suppose to be our instinctive moral code — that words like ‘fair,’ ‘just’ or ‘equitable’ must in the end be chased, and find refuge. So when a politician says ‘We should do this because it is the right thing to do’ or ‘We should make the cuts in this way because it’s the fair way’, he offers not an explanation but a tautology. The ‘should’ follows from ‘right’ or ‘fair’, as indeed the right or fair follow from the should. They are all saying the same thing.

Unfortunately, however, our supposedly innate sense of right and wrong varies sharply between epochs and cultures, and even between individuals in the same epoch or culture. Early slave-owners (and perhaps their slaves too) did not feel the arrangement was unfair. ‘Shall the law punish one man for making a fool of another?’ asked a 16th-century English judge in a fraud case, supposing the question to be rhetorical and the answer an obvious No. From that apparently platitudinous hymn, ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’, the Church of England has now removed the verse ‘The rich man in his castle, / The poor man at his gate, / God made them, high or lowly, / And ordered their estate.’

So the politician who appeals to ‘fairness’ as a justification for the way his spending cuts fall, can in the end be offering no reason for his policy beyond an appeal to what he hopes is a general sense of the morality of the age.

This shifts, and is shifting. Through our lifetimes it has been shifting, with fluctuations, towards a greater equalising of outcomes as well as opportunities. The signs now — not least in our turning away from the word ‘equal’ and toward the less constraining word ‘fair’ — are that it is shifting away from the morality of equal portions, and towards the morality of competition. I hope so.

Comments