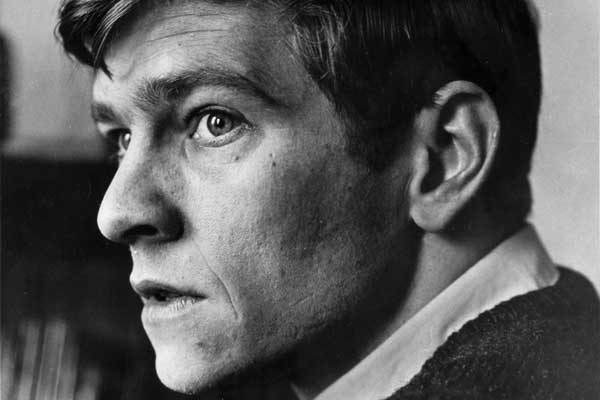

‘You can’t talk about what might have been,’ says Tom Courtenay, reflecting on an acting career that blazed like a meteor the moment he left drama school and is now in its sixth decade. ‘The things you might have done, the films you might have made. I just didn’t feel comfortable with the world of international cinema. I saw a bit of it, the so-called hellraising and what have you, and realised it wasn’t for me’.

Not talking about the things he chose not to do doesn’t mean there is nothing to talk about. A trim 75, Courtenay has enjoyed a life blessed with good things, from the day he passed his 11-plus (one of only two boys in his class who did) to win a place at Kingston High School in Hull, where Alan Plater, the writer, was two years his senior. The working-class lad from the fish docks became head boy, before he went from the Humber to University College London, where his acting affected his English studies, and then Rada, where he found his true voice.

Upon graduation in 1960 it was straight into the Old Vic production of The Seagull, as the disaffected student Konstantin. Then came an extraordinary run of film roles: Billy Liar (which he also played on stage), Colin Smith in The Loneliness of the Long -Distance Runner, and Pasha Antipov in David Lean’s adaptation of Dr Zhivago, a worldwide smash. Here were three more disaffected young men, in Yorkshire and Russia, a world away in time and mood from Quartet, Courtenay’s latest film, which was released this month.

Directed by Dustin Hoffman (making his debut behind the camera at 75) from a screenplay by Ronald Harwood, 78, with Courtenay, Maggie Smith, Pauline Collins and Billy Connolly playing opera singers in a retirement home, Quartet is a divertissement about mortality that takes its cue from the closing line of Larkin’s ‘The Old Fools’: ‘Well, we shall find out.’ Audiences are enjoying it, and clearly the company enjoyed making it.

‘Dustin is so quick, so funny,’ says Courtenay. ‘Before a take he would say, “All right, everybody, it’s time to feel self-conscious and nervous.” He’s a natural storyteller, and knows the business inside out. His father was a prop man and one of the prop men on the set said, “We’re getting the benefit of his expertise.” ’ Hoffman paid for the time they went over, too, three weeks’ shooting from his own pocket. A large cigar for that man.

Should Courtenay have made more films? Zhivago raised him to the nursery slopes of stardom, and The Dresser two decades later brought a second nomination for best supporting actor at the Oscars. ‘I should have done, I suppose, but the kind of films I wanted to make were not being made, and I kept getting offered things that I didn’t particularly like. I probably turned my back more than I intended.

‘I remember, after Zhivago, that many of my friends in the business were quite disdainful about the success of that film, and it really was a huge success. Billy Liar and Runner were big films here, and found an audience in Europe, but they made little impression in America. Zhivago did. Years later, I was talking to [the lyricist] Herbert Kretzmer’s wife, who told me that all the girls at her high school in the States were in love with Pasha, and I was thinking “Who the bloody hell is Pasha?” It had slipped my mind.

‘I felt at the time that if I spent more time on stage I would learn to act better. To have a long career I needed to work on stage. An American actor said back then that I had not paid my dues, or words to that effect, and he was right. On the set of Zhivago there was a shot showing a group of us in our chairs, with our names on the back of the chairs, and our faces turned round to face the camera. The names were Guinness, Richardson and Courtenay. I was sitting between Alec and Ralph, and I didn’t feel I deserved to be there. Rod Steiger was in that film, too!

‘I was quite shy, and my fame was so sudden. I was discovered, if you like, in my penultimate term at Rada, in a show called Shut Up and Sing. From college it was straight to the Edinburgh Festival, with the Old Vic, and then I was replacing Albert [Finney] in Billy Liar in the West End. I was running before I could walk, and what I really wanted to be was an actor.’

As he said some years ago, when pressed about his apparent lack of a public profile, ‘When you see who is in fashion, it’s not such a bad thing to be out of it.’ Like Finney, his great friend, and co-star in The Dresser and (on stage) Art, he has done only what he wanted to. It is a far cry from today’s instant stardom, as often as not bestowed upon actors who have no intention of paying their dues.

If he harbours a regret, it may be that A Day In The Life of Ivan Denisovich, directed by Caspar Wrede in 1970, has never been acclaimed as widely as he would like. ‘I thought that was a very beautiful film. Solzhenitsyn thought I was too young for the part, and he was right. But it was a lovely piece of work.’

He keeps his hand in. There was Little Dorrit for the BBC, and an appearance on the Christmas edition of The Royle Family, set in Manchester, where he has done much of his best work on stage, at the Royal Exchange Theatre. The Dresser began life there, and he has filled the roles of King Lear and Uncle Vanya in the city’s remarkable in-the-round ‘space module’. His last appearance on the London stage, nine years ago, was Pretending To Be Me, the one-man tribute to Larkin, who, of course, lived in Hull. ‘I might bring back the Larkin,’ he says, thinking as he speaks.

Unlike Finney, he accepted his knighthood. ‘I thought of my father, who had a disability pension, and my mother. They’d have said, “Oo, Tom has got a knighthood,” like they used to say “Tom is head boy.” ’ If you have not read Dear Tom, Courtenay’s tribute to the mother who died in 1962, just as his career was taking off, do not deny yourself the pleasure. Weaving Annie Courtenay’s letters with her son’s commentary on his early years, it is a glowing tribute to a working-class life that no longer exists.

‘I loved writing the book. Not once did I look at the clock, and wonder whether it was time for the first drink of the day’. When that drink is poured, and Schubert is on the turntable, and talk turns to Hull City, and the great Yorkshire cricketers he grew up with, and the headmaster, Dr Cameron Walker, who once gave him a ten-bob note to see him right on that first visit to London, he looks happy with his lot. As he might be. It has been quite a life.

Comments