As a young music critic, Bernard Shaw poked fun at anyone who thought Mendelssohn was a genius. Shaw conceded that Mendelssohn was capable of touching tenderness and refinement and sometimes ‘nobility and pure fire’, but his music was marred by kid-glove gentility, conventional sentimentality and – worst of all – ‘despicable oratorio-mongering’. Shaw’s pet hate was St Paul, with its ‘Sunday-school sentimentalities and its music-school ornamentalities’. He was only slightly less catty about Mendelssohn’s other oratorio, Elijah. Although he acknowledged its ‘exquisite prettiness’, he concluded that its composer was ‘a wonder whilst he is flying; but when his wings fail him, he walks like a parrot’.

Nobody needed reminding that Pappano is one of the greatest opera conductors of our age

Now the pendulum has swung, but not all the way. Elijah is acclaimed for the monumental sweep of the choruses, the exquisite woodwind sonorities – it was written soon after the incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream – and some sweet melodies. But it lasts nearly two-and-a-half hours, for God’s sake, and it’s hard to forget Shaw’s jibe about music schools: the modulations have a seamless textbook quality, without a whisper of dissonance.

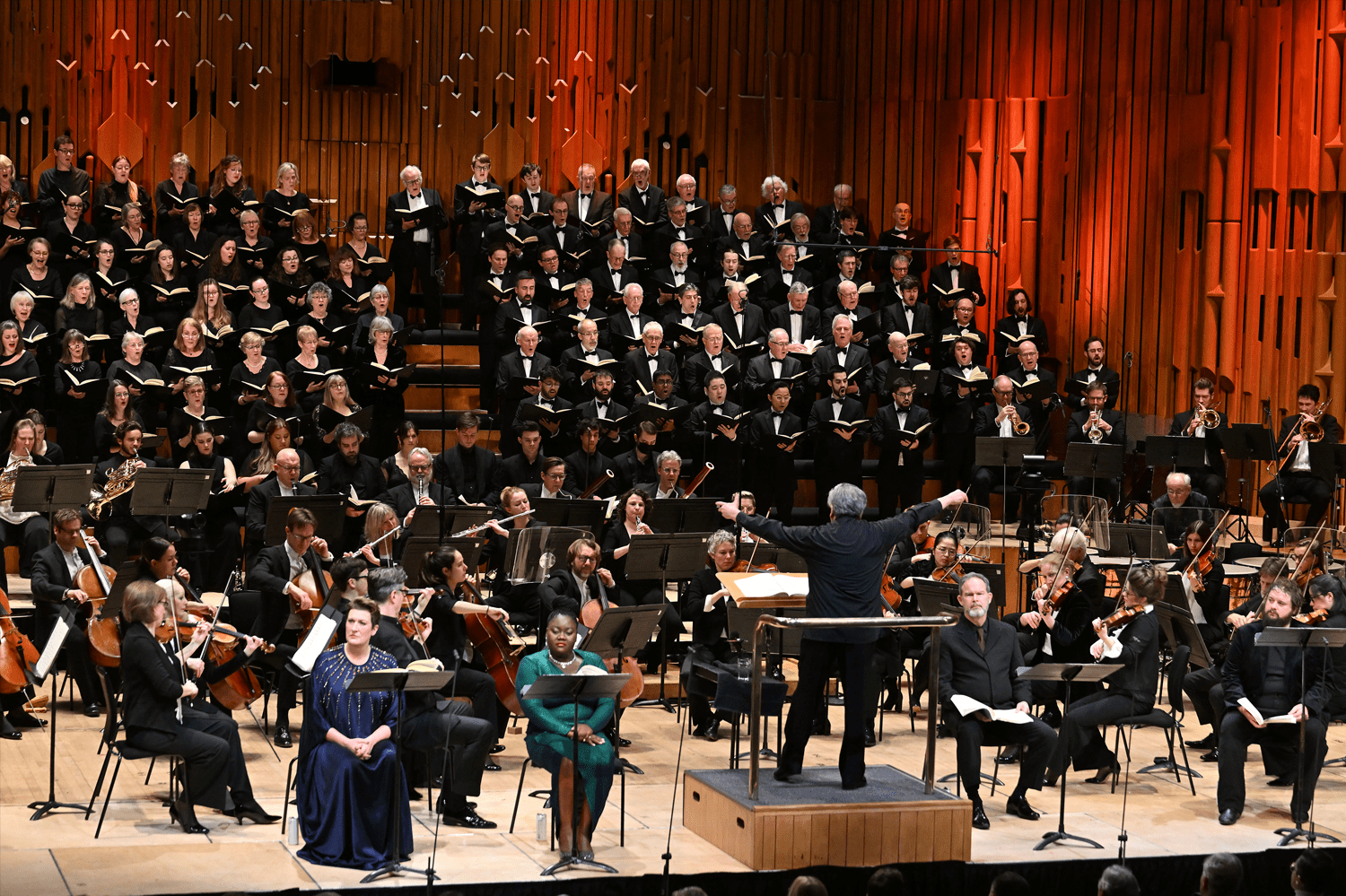

But I did forget it at the Barbican on Sunday night, thanks to an electrifying performance by the London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra under Sir Antonio Pappano. Nobody needed reminding that he’s one of the greatest opera conductors of our age. In the overture, his thrusting tempo made Mendelssohn sound like Verdi. During the recitatives, the intervening chords hit like thunderbolts; surely a fatal stabbing was in the offing.

Elsewhere, he applied surges of rubato to repeated chords that reminded me of Berlioz. But what he really showed us was that, despite the tidy harmonies and dusting of caster sugar, Mendelssohn hadn’t entirely lost the charisma that produced the teenage miracle of his Octet.

The chorus was on fire, at full size but ferociously agile, more than a match for the snarling brass (Mendelssohn’s expert orchestration again). A chamber choir from the Guildhall lightened the textures; the soloists were all in good shape, though Gerald Finley’s Elijah lacked the prophetic rage of, say, the young Bryn Terfel and was sometimes overpowered by Pappano’s slashing accompaniment.

I’m afraid my heart sank when I saw that Dame Sarah Connolly was the mezzo, since I’m allergic to her voice – when she’s speaking, that is: she’s bitter about Brexit and won’t shut up about it. But the flash of steel when she sings is perfect for oratorios – which may sound like a back-handed compliment, but that’s what Elijah is, after all. She’s been at the top of her game for more than 30 years. Incredible.

And so an evening of despicable oratorio-mongering passed thrillingly. To say that this bodes well for Pappano’s tenure at the LSO is putting it mildly. And it was some consolation for what happened on Friday night at Milton Court, where the Academy of Ancient Music gave a period performance of all the Brandenburg Concertos. Unfortunately the period they recreated wasn’t 1721, when Bach presented his ‘Six Concerts Avec plusieurs instruments’ to the Margrave of Brandenburg. It was the 1960s, before musicians had learned how to play ‘authentic’ instruments, as they were called at the time.

I wonder if the root of the problem is that Cummings is just too nice

In the First Concerto, Bach has two horns playing across the rhythms of the orchestra, triplets against semiquavers, and generally leaping about virtuosically. That’s a risk if you use valveless hunting horns, as period groups do, since they weren’t designed to play lots of notes and nearly always sound laboured. It’s even more risky if, like AAM director Laurence Cummings, you reduce the other parts to an anorexic minimum. As it was, the horns’ noisy distress spread around the group, with ear-splitting wobbles from the oboes, dodgy intonation from the strings and a general whiff of vinegar.

The valveless solo trumpet in the Second Concerto – another insanely difficult part – didn’t fare much better. Cummings scampered happily through the harpsichord cadenza in the Fifth, but by then it was too late – and in any case, issues with tuning resurfaced in the Sixth.

I wonder if the root of the problem is that Cummings is just too nice. At the end of that carriage-wreck of a First Concerto he wandered around congratulating each and every musician. Imagine if they’d been playing for Sir John Eliot Gardiner. They’d need police protection.

Comments