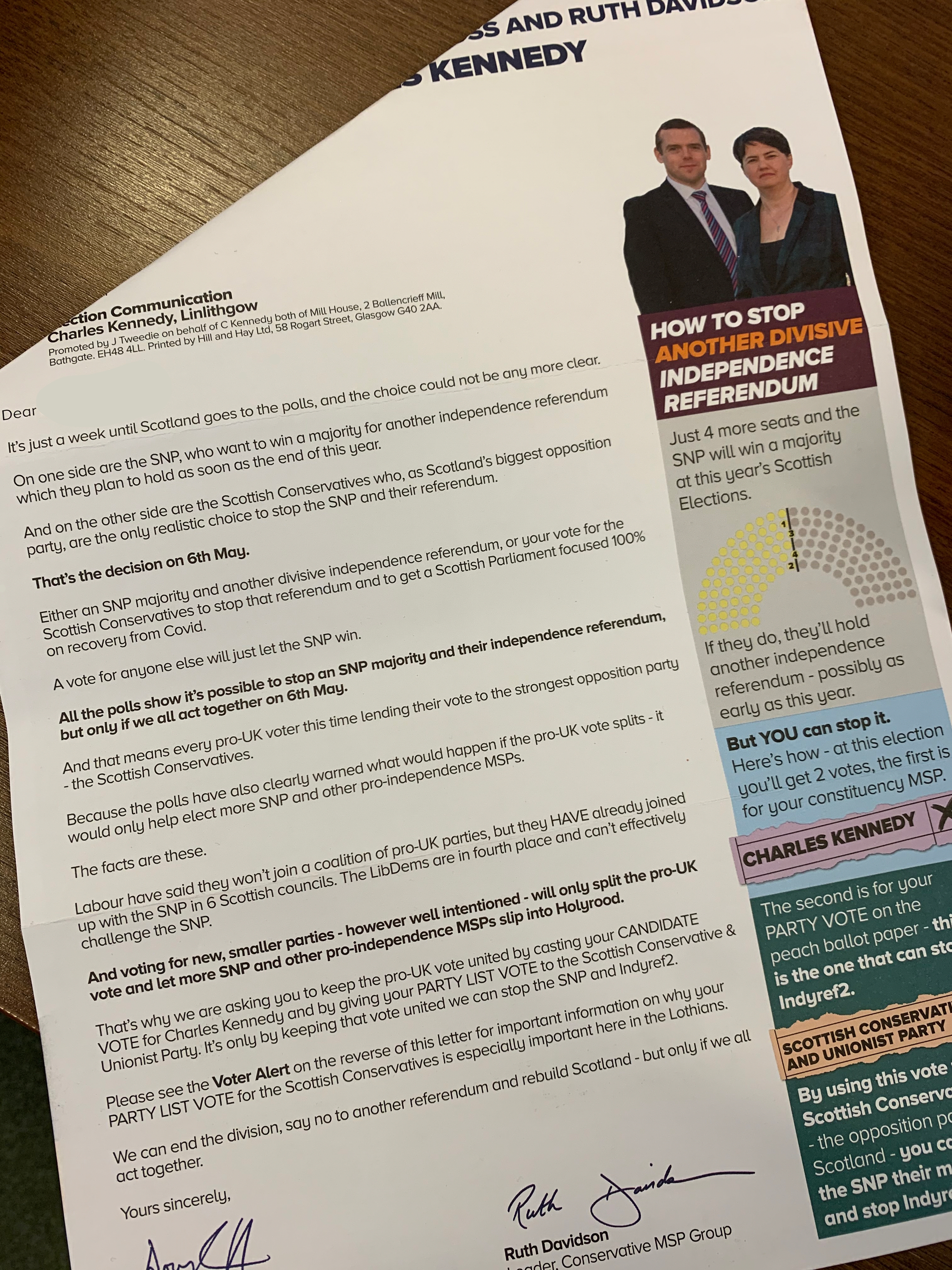

Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross has barely been seen in public without his chaperone, Ruth Davidson. She has accompanied him around the Holyrood elections campaign trail with such devotion that it’s unclear who is standing for election and who is the actual party leader.

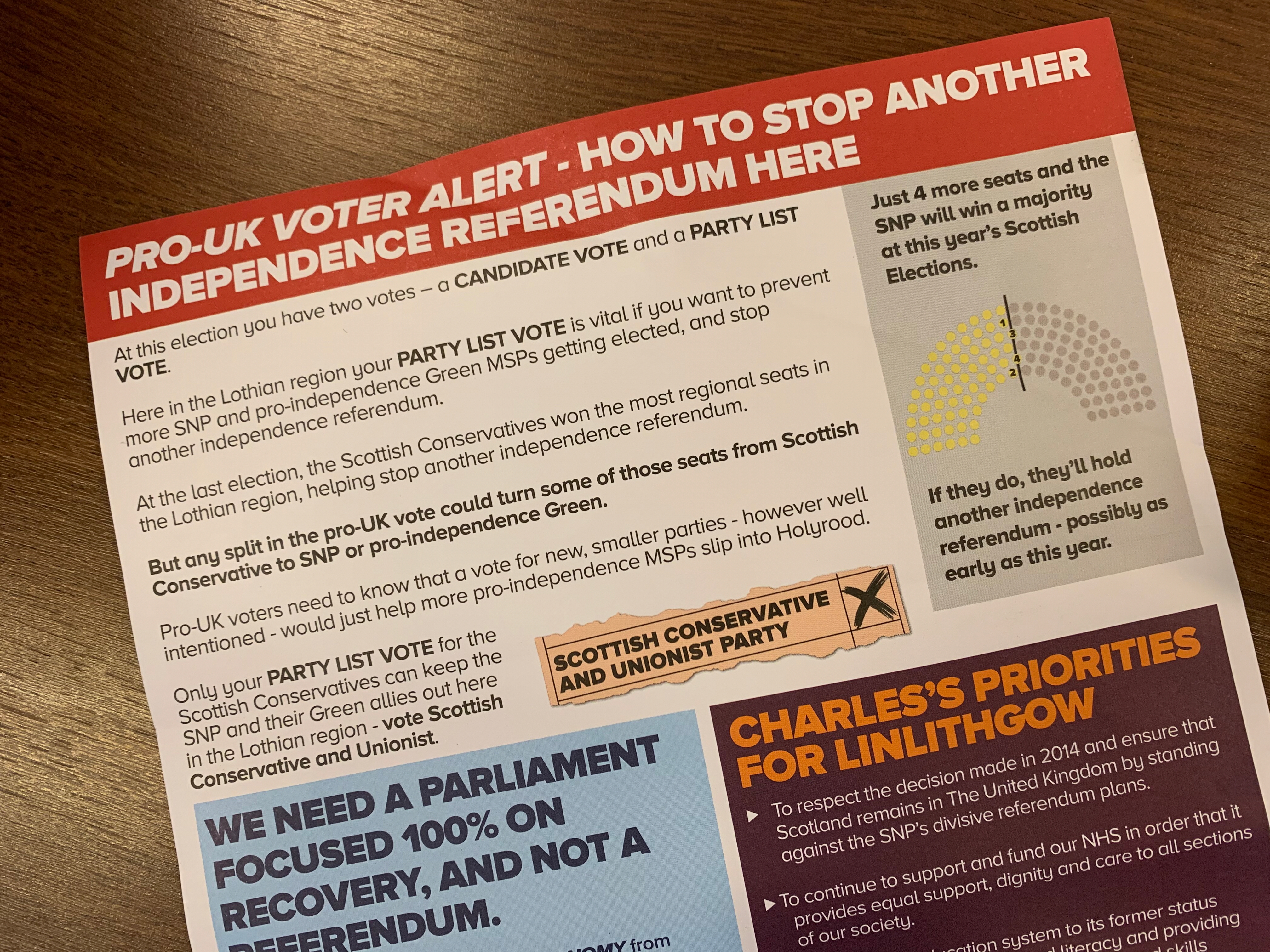

The pair are campaigning in Edinburgh today and have sent out these letters – pictured below – to pro-Union voters. They have also launched an ad van and starred in a party political broadcast together. Perhaps ‘starred’ is an exaggeration for Ross, who played more of a cameo role in the PPB last month, with Davidson taking the limelight.

Douglas Ross has struggled to have any kind of breakthrough moment in this campaign.

Davidson is, in case you are understandably confused, not standing for election and will shortly take up her seat in the House of Lords. Neither is she the leader of the Scottish Conservatives: she stood down in 2019 because she wanted to spend more time with her young son. There has even been a leader in between her and Ross: though, once again, you might be forgiven for having forgotten Jackson Carlaw, given one of the reasons he stood down was that his colleagues deemed him not very effective.

Now, the argument that the Scottish Conservatives make officially is that Davidson has been the leader of the MSP group up until these elections and she has taken First Minister’s Questions up to this point too, so she has still had a very important role in the party. But her omnipresence in this campaign does show what a loss to the party her resignation as leader was, and also how unprepared it was for having anyone else at the helm.

Davidson had built up such a strong brand as a fun, straight-talking politician who reintroduced Scottish voters to the Conservatives, but there seemed to be little thought given to whether anyone around her might be able to cultivate the same appeal. Ross has certainly struggled to have any kind of breakthrough moment in this campaign.

The focus of the Scottish Conservative messaging has largely been to warn the party’s already avidly pro-Union base about the dangers of another referendum. By contrast, Scottish Labour has been arguing for a recovery, not a referendum, in an attempt to reach out to those in the middle. The two parties are competing to take second place and be the official opposition, but they could also dovetail well in the coming years if they continue to take these different positions.

That’s perhaps why there is less anxiety among pro-UK thinkers about how Ross/Davidson’s party does this week than there is about the recovery of the Scottish Labour Party.

Comments