Venice and Alexandria were, as far as the Venetians were concerned, twin cities. According to legend, St Mark had visited Venice before going to Alexandria, where he preached, performed miracles and was martyred. When two Venetian merchants stole the saint’s remains from Alexandria in 828, they were merely fulfilling the prophecy of the Angel that had appeared to Mark in the lagoon and, addressing him with the ringing words ‘Pax tibi Marce, Evangelista meus’, had predicted that a great city would arise upon these waters, which was to be his last resting place.

The origins of the mythical links between Venice and Alexandria were as much mercantile as mystical. For hundreds of years the spice trade with Alexandria yielded the immense profits with which the Venetians built that great city on the waters.

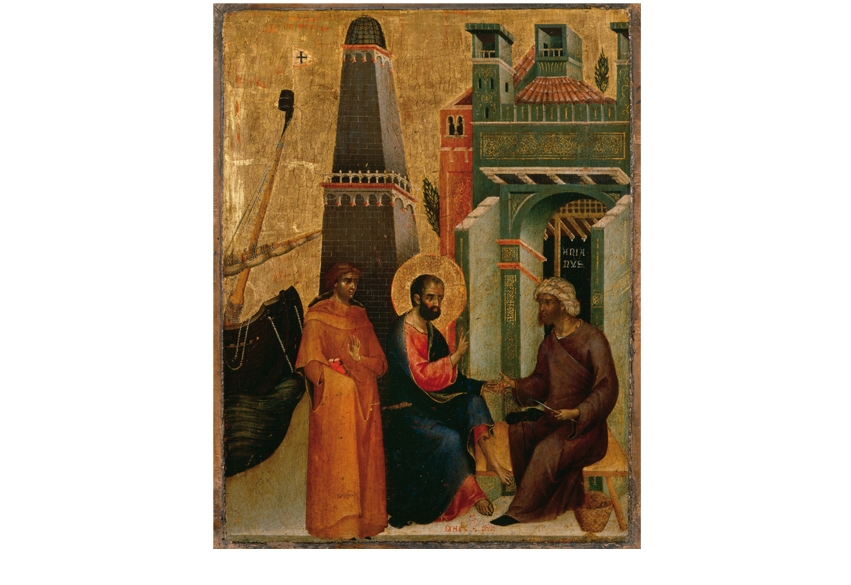

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, became a shorthand emblem for the Egyptian port. It appears prominently in a miracle scene in a 14-part panel depicting the life of the Evangelist, and the translation of his relics to Venice, that greets visitors at the beginning of this engaging exhibition.

The panel was executed by Paolo Veneziano and his sons Luca and Giovanni for St Mark’s Basilica in the mid-1340s, commissioned by Doge Andrea Dandolo, the last of the doges to be buried in the Basilica in 1354.

The lighthouse figures in five mosaics in St Mark’s and, when the campanile of the Cathedral church of San Pietro di Castello was redesigned and faced with brilliant white Istrian marble in the 1480s by Mauro Codussi, it was in imitation of the famous Alexandrian lighthouse. Ironically, by this time no trace of the Egyptian original remained, having been replaced by a Mamluk fortress.

The first Venetian diplomatic agreements were made with Egypt’s Islamic rulers in the early 13th century. The papacy deplored this trade with the infidel and the interdicts of John XXII led to its suspension from 1320 for 23 years. But for most of the time it was business as usual, the Serenissima’s galleys carrying merchants, pilgrims and adventurers to the East and returning laden with spices, textiles, carpets, metalwork, glass, rare pigments and other Oriental luxuries. Venetian package tours to the Holy Land included meals, the services of experienced guides and travel insurance.

This heyday of Venice’s maritime empire is vividly evoked in a section of the show entitled ‘The Journey’, through contemporary paintings, antique prints, maps and a superb 12-and-a-half-foot-long model of a light galley with 156 miniature rowers.

Diplomatic exchanges brought to the Treasury of San Marco prized pieces, such as the two 10th-century Fatimid rock-crystal vessels, as well as refined Islamic metalwork and ancient Egyptian pieces, among the first to reach Adriatic shores since Roman times. Examples of these are displayed in a ‘Treasures, Commerce and Politics’ section, together with Arabic and Ottoman documents from the Venetian State Archive, reflecting the continual traffic of communications on commercial and political matters.

The discovery by the Portuguese in 1497 of the route to the Indies via the Cape of Good Hope was as great a challenge to the Mamluks as to their Venetian trading partners. They even discussed a joint venture to revive the old Egyptian and Roman dream of digging a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.

But, as the second half of the exhibition demonstrates, even as the lagoon Republic’s virtual monopoly on the spice trade came to an end, Venice continued to serve as a bridge between Europe and Egypt.

In 1505 the Aldine Press published the original Greek text of Hieroglyphica, an ancient treatise on their decipherment, one of a series of books on aspects of Egypt printed in Venice. A number of these key works are displayed with the first ever printed Arabic copy of the Koran, typeset in Venice 1537–38.

The antiquarian aristocrat Marco Grimani, who was in Egypt in 1535–36, described and measured the Pyramid of Cheops. And in 1584 the Venetian Consul Giovanni Emo dissuaded the Ottoman governor from blasting a hole in it in search of treasure.

In the 17th and 18th centuries some major private collections of Egyptian antiquities were amassed in the city, only to be dispersed after the fall of the Republic in 1797. They are represented by some notable items now brought together from various institutions, along with prints of interior designs and archeological views by the Venetian artist Giambattista Piranesi, an early connoisseur of Egyptian art.

The 19th century saw a new generation of Venetian adventurers in Egypt, whose travels are the subject of the last sections of the exhibition: the archeologists and explorers Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Giovanni Miani, and the artist Ippolito Caffì. Belzoni is responsible for the presence in the British Museum of the colossal bust of Rameses II, weighing over 7 tons. Still one of the Museum’s most impressive exhibits, it is also supposed to have been the inspiration for Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’.

Comments