The holiday season is upon us, but it’s nothing to celebrate, says Lloyd Evans. Tourism is torture, no matter how you do it

Oh God. Here it comes again. The days lengthen, the temperature climbs, the pollen spreads and the mighty armies of foreign invaders prepare to make their move. It’s not illegal immigrants who cause my heart to sink at this time of year. Those brave defectors deserve our admiration for their persistence and ingenuity. They travel here in conditions no westerner would tolerate. They cling upside down to the exhaust pipes of juggernauts. They squeeze into the drums of imported washing machines. Unlike casual holiday-makers they’re serious about this country. They’re here to learn English, find a job, raise a family, get sick and die. Their long-term commitment is manifest and honourable. It’s the part-time nomads I take issue with, the away-day brigade of gawpers and voyeurs.

Those lucky enough to have studied Leisure Management at one of our top universities will know that holidays fall into three broad categories. First, the beach break or inactivity holiday. This is a dress rehearsal for retirement and involves many hours on the sun lounger reading Ian McEwan and getting zonked on cocktails while the solar furnace gently cooks one’s flesh to the orangey roughness of a Florentine roof-tile. If you want a beach holiday but don’t like beaches, you can book a berth on the new class of ‘super-cruiseliners’, or ‘care homes with lifeboats’ as their crews call them.

Second, there’s the hyperactivity holiday. This has numerous life-threatening varieties: paragliding, pearl-diving, Alp-scaling, cave-loitering, zebra-stalking, marlin-snagging, turtle-bothering, tsunami-surfing and so on. The object is to have a near-death experience and put the local emergency services through their paces.

Third, there’s the city break which, to a certain type of exuberant Englishman, involves going to a city and breaking it.

Readers of this magazine may feel these classifications don’t apply to them and that they journey abroad on a higher intellectual plateau than the crisp-gobblers at the back of the plane. This is an illusion. The public-school banker flip-flopping around Rome in his shorts and straw hat and glancing at his Architecture of the Italian Renaissance (Thames & Hudson, 1963) while struggling to pronounce Brunelleschi correctly is no different from the half-naked skinhead who visits Rome for a soccer final and lobs a bar-stool through a plate-glass window before being jumped on by the carabinieri and kicked senseless. The colorations may vary but the species are identical.

Both specimens have temporarily swapped their real self for an idealised persona based on some earlier version of the English character. The banker has become an 18th-century milord on the Grand Tour. The skinhead (who may be a banker too, incidentally) has become a marauding 7th-century Viking. Both have adopted habits of dress they would not follow at home. Both want to interact with an alien society and appropriate a part of its culture within the limited bounds of their physical or mental powers. Both will return from their escapade with trophies to display. The banker will have his photographs of the Palazzo Farnese and his newly acquired appreciation of the Square Mile’s neo-classical facades. The skinhead will have his battle-scars and his newly acquired membership of Interpol’s hooligan blacklist. Both are more or less indifferent to Italy and its culture and have chosen Rome quite arbitrarily as the backdrop for a ceremony of spiritual rebirth and self-realisation. The one glaring difference between them is that the skinhead knows how debased his motives are, while the banker, lacking the skinhead’s self-awareness, imagines himself a chap of infinite delicacy and refinement.

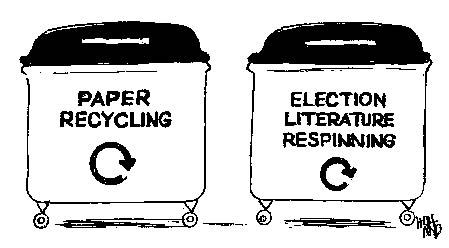

Tourism, like torture, brutalises both the perpetrator and the victim. Visit the Tower of London and you’ll find an amazing and eccentric medieval river-fort transformed into a stage-managed Disneyworld staffed by noddies in pantomime costumes spouting clap-trap about thumbscrews and beheadings. The corruption is symmetrical. Foreign visitors have reduced us to a handful of picture-book truisms and we’ve had the same diminishing effect on them. We think we’re learning about a country when all we can really see is how successfully the natives have altered the place to gratify our prejudices.

Mass tourism has turned the decent self-respecting Mediterraneans into folk-dancing, zither-smiting, smock-wearing parodies of their ancestors. Go to Turkey and some unemployed cornerboy claiming to be a whirling dervish will rotate on the spot for you for a few minutes before pocketing your gratuity and wobbling off to be sick in the bushes. If you visit Sudan, even in its lush and fertile hinterland, the locals will assume you’re looking for evidence of their best-known product — starvation. Some wasted old crone will be prodded awake and dragged from her hut by excited villagers piping, ‘fameen veecteem’, while holding their hands out.

One of the most depressing aspects of foreign travel is watching oneself attempt to communicate. Unless you’re a master linguist you’re likely to cause distress whenever you open your mouth. Even here in England my conversation is known to cause drowsiness. Abroad, when I break into a foreign tongue, I can endanger life. I’m all too familiar with that look of outraged Gallic pride that crosses a Frenchman’s brow when he sees a rosbif about to essay the language of Racine and Voltaire. It’s not an expression I take any pleasure in provoking so I prefer to advance my thoughts in a mutually intelligible pidgin. But this narrows my table-talk to the crudest phrase-book inanities. ‘Church nice. Sun hot. Tony Blair war criminal.’ And once the conversation has settled into English I find my hosts all too willing to unfurl a distorted version of our language and harry it to death before my eyes.

The inability to communicate renders travellers effectively deaf and dumb. This explains why they seek out the physical gratifications of food, scenery, watersports, binge-drinking and so on. With their powers of speech and comprehension eradicated, their other senses are automatically heightened. Some argue that this is the very essence of travel, the chance to relax in the comforting splendours of five-star luxury. And posh hotels certainly like to create the illusion of limitless choice with their ‘24-hour room service’, but the reality is that they give you only what they feel like giving you when they feel like giving it to you. The contract is based on mistrust rather than hospitality. Their motive is self-interest and the visitor’s only means of leverage is bribery so he never quite shakes off the feeling that he’s a hostage, albeit with a walk-in shower cubicle and some handy little bottles of triple moisturising body wash.

When Horace questioned the merits of tourism he came up with this soundbite: ‘They change the sky, not their soul, who run across the sea…’. I can see myself there pretty clearly. My soul is beyond salvage and the sky looks just fine from where I’m sitting. So while the rest of the world packs its travel bag with sunburn cream, mosquito spray, indigestion tablets and insurance documents guaranteeing five million pounds worth of emergency medical expenses, I’m staying right where I am with my bookcase, my music collection, my cheese board and my cellar of plonk. Send me a postcard.

Comments