If you think that a room full of solemn people in groups of four play- ing duplicate bridge is deeply depressing, then this young-adult novel is not for you. If, on the other hand, that array of concentrated brows fills you with an urge to compete, then you may derive some pleasure from it. And if you are a keen player unable to convince your teenage children of the merit of the game, then you might consider this a useful present.

Lester Trapp, a brilliant bridge-player, now blind, requires a cardturner to speak out the cards for him at his bridge club. He asks his nephew, Alton, a high-school boy looking for a summer job. This being America, the nephew has a licence and a car and, in a laid back way, is content to drive his elderly uncle to his club and help him out. Alton’s mother has long had her sights on Trapp’s considerable inheritance, and before this offer comes along would urge her son to ring the old man and say: ‘I love you, Uncle Lester. You are my favourite uncle.’

Alton’s introduction to the game of bridge serves as the same for the reader. Trumps are described early on, further rules in succeeding chapters, and more complicated conventions and methods of play as the story progresses. The instructive paragraphs (‘A finesse is a cool play’, followed by detailed examples) are prefaced by a small drawing of a whale; this is because Alton would skip the factual descriptions of whaling ships when studying Moby Dick. The knowledgeable player or uninterested reader can jump.

Attached to this unusual primer is a story about a corrupt and vengeful senator, his beautiful bridge-mad wife, Annabel, and a doomed love affair. Lester and his bridge partner and inamorata, Annabel, were all set to triumph at the national bridge championships when the senator intervenes, kidnaps his wife and has her put in an asylum, where a couple of years later she commits suicide.

The cardturner says nothing as he absorbs the game at his uncle’s elbow, but he starts playing with Annabel’s granddaughter, Toni, a strange schizophrenic girl and a former cardturner herself, and ends up partnering Toni in unusual circumstances at the national championships. Alton is an agreeable narrator, ‘with a philosophical bent’, who learns much about life as well as bridge during his eccentric summer job.

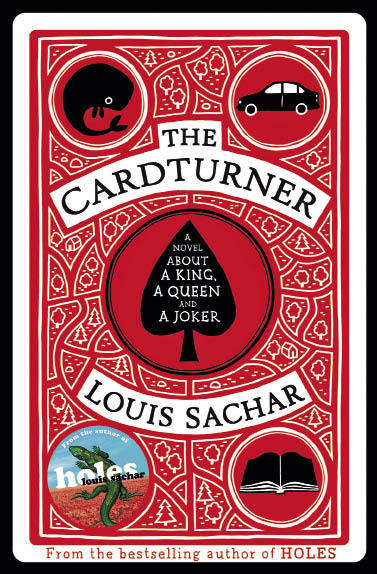

Louis Sachar, a successful children’s author with the prizewinning Holes to his name, as well as other titles such as Sideways Arithmetic from Wayside School and the more promising sounding Dogs Don’t Tell Jokes, is a dab hand at teaching by story. The book does not work as an adult novel — sketchy characters, all very predictable — and possibly not as a teen read — too technical — but is nevertheless light and fun, and must have been, for Sachar, a way of combining his passion for bridge, which he plays at tournament level, with his ability to write stories which educate as they go along. q

Comments