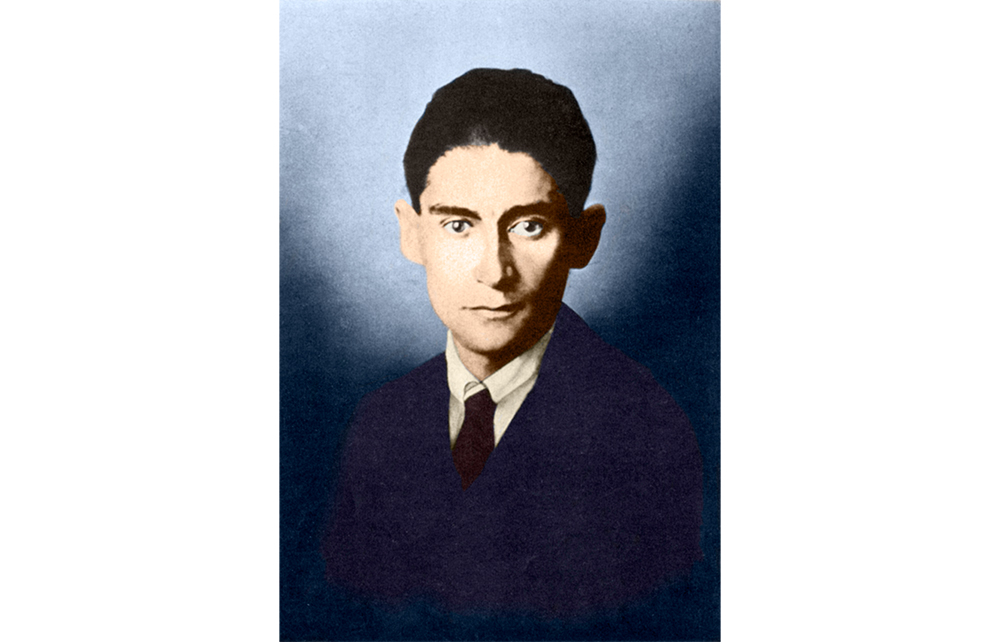

Two books in one: you flip it over, and it becomes the other. A Winter in Zürau is about Franz Kafka’s stay in a small Bohemian village with his sister Ottla after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. Or, as Gabriel Josipovici arrestingly puts it in the preface: ‘One day in the summer of 1917 the writer Franz Kafka woke up to find his mouth full of blood.’ (The echo of the opening line of Metamorphosis is surely deliberate.) Here, in isolation, he recuperated, or tried to. He wrote to Max Brod: ‘I’m not writing. What’s more, my will is not directed towards writing. If I could save myself… by digging holes, I would dig holes.’

Josipovici quotes this, and adds that there is a photograph of Samuel Beckett ‘doing just that’ in the second volume of his Collected Letters. Josipovici likes mentioning Beckett from time to time, which pleases me. But Kafka, as so often in his letters, wasn’t telling us the whole story. Of course he wrote in Zürau – he was Kafka, for goodness’ sake – and he produced what Brod eventually collected under the title of The Zürau Aphorisms, or, less snappily, Reflections on Sin, Hope, Suffering, and the True Way.

The 181 pages of Josipovici’s monograph, if that is the word, are difficult to summarise, but they are a mixture of biography, literary criticism and psychological insight, and make up one of the best things on Kafka I have read. As his previous volumes of literary criticism and essays attest, Josipovici is astonishingly readable; his prose simply takes you by the hand. At one point he quotes Kafka complaining about mice, but also about the cat that was meant to deal with them, which keeps soiling his room. (‘How hard it is to arrive at an understanding with an animal on this question.’) As Josipovici says: ‘This is going from paranoia to P.G. Wodehouse to paranoia and back to Wodehouse in a few sentences and with remarkable ease.’ Josipovici likes mentioning Wodehouse from time to time, and this also pleases me.

Now turn the book over, like an LP. (Josipovici used a similar two-in-one trick with Mobius the Stripper in 1972). A Winter in Zürau’s inside-page blurb begins: ‘Fiction and non-fiction are two sides of the same coin. Or are they? Kafka is in flight.’ Partita’s blurb begins with the same two sentences and then continues: ‘Michael Penderecki is in flight.’ Apart from that there is little to connect the two books and I have already spent too much time trying to force a connection. No matter: this is fiction, and Josipovici has his own way of doing it, and it is, like his non-fiction, astonishingly readable, considering that he regards himself as a modernist in the grand tradition. He once said of his fiction: ‘Suddenly it came to me. It was not that I didn’t like the forms of description I was using; I didn’t like any form of description. What’s more, I suddenly realised I didn’t need it.’

So we have novella told mostly in dialogue, but so deftly that you never struggle with trying to work out who is talking. It begins with a man called Karim paying a visit to Penderecki, who has been sleeping with his wife. He shows him a flick knife and tells Penderecki that if he’s is still there the next day he will kill him. Penderecki gets the hint and goes on a journey, which takes him from London to Paris to Nice to Domaso to Sils Maria to Zurich and back to London. (I might have missed a location or two, it zips along.)

At the beginning, he’s just fleeing for his life with a suitcase; but in Nice he meets Charlie, a nightclub singer, with whom he has a heartbreaking affair. She’s reminiscent of the kind of heroine you get in nouvelle vague films – flighty, enigmatic, hugely desirable and annoying as hell. (She makes him cycle from Nice to Monaco, for crying out loud.) In fact, the whole novella may as well be the script for a nouvelle vague film, and I say that in an entirely complimentary way. Reviewing Josipovici’s 2010 novel, Only Joking, I wrote: ‘Whether this is a serious work of art or simply a jeu d’esprit is something that, after a week, I have yet to make my mind up about.’ I could say the same here. But who cares in the end? It’s a romp, and highly enjoyable.

Comments