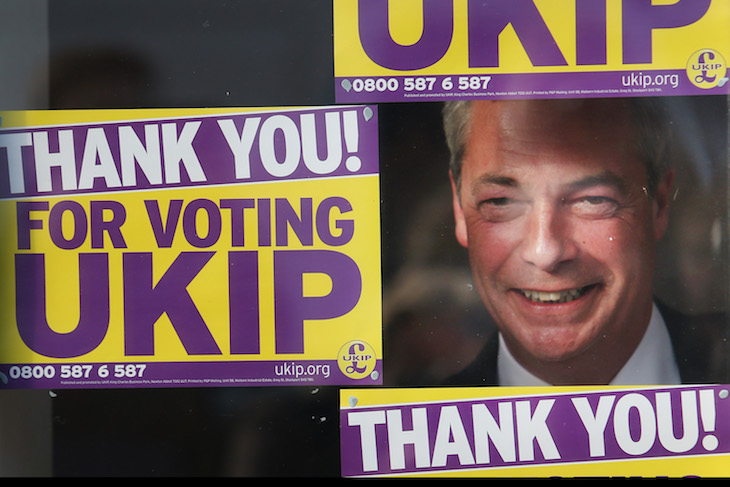

‘The return of Ukip’ declared the headline on our cover story last week. The polling boffin Matthew Goodwin to whose analysis this referred was in fact more careful. Professor Goodwin did argue, however, that the potential may be there for a Ukip revival.

So it may. But the figures for new recruits that he cites are modest. The doubt he describes as surrounding Nigel Farage’s chances of a comeback is real. Ukip’s present stance under its latest leader Gerard Batten (who has developed links with the campaign for the disgraced and imprisoned former leader of the English Defence League, Tommy Robinson) looks crazier by the week. And there’s a world of difference between disappointed Brexiteer respondents telling pollsters they’d support Ukip, and the solid organisational revival that would be required of that carcass of a party if it is to present the Conservatives and Labour with a real threat in a real general election.

Goodwin is, rightly, gingerly with his claims. After reading these with care my estimation of Ukip’s chances diminished rather than grew. I had forgotten the nasty and sinister Tommy Robinson story. I’d overlooked the alt-right connections, the racist obscenities of social media campaigners, and all that Breitbart business. Our country is not redneck America. It seemed to me that Ukippery was going niche just when there might be a market for it to go mainstream. To my eyes, the picture Goodwin painted was of a movement lurching off into the sort of company that will attract fierce enthusiasm among the spittle-flecked brigade, but which respectable voters will shy away from.

Instead, therefore, of Ukip’s impending return, I sensed (I don’t accuse Goodwin of this) an appetite among some of the bolder Tory Brexiteers to put the wind up Remainer Conservatives (and there are millions of us) using the spectre of a revival of the hard right: the implicit message being that Tories must harden up their Brexit offer lest a competitor enter the market. But Ukip isn’t back, and isn’t likely to be.

And that’s a pity. I’m missing the UK Independence Party. I miss it for its useful capacity to act as a poultice for the mainstream Conservative party, drawing off the poison. Now Ukip has all but closed for business, its former clientele among the electorate have had nowhere to go to but the Tories, and appear to have come swarming back to puff the pretensions of absurd figures such as Jacob Rees-Mogg and his friends. It was better when many of these voters took their snarls and fumes about the ‘liberal establishment elite’ off to a different party, more hospitable to their paranoid politics. Now they’re back among us, wearing the livery of Tory Brexiteers, conservatism is the worse for it.

Besides thumbing my nose at the zealots among Brexiteers (always a pleasure), I have a serious argument to make about the geography of modern party boundaries — and, ironically, it is my old friend Tim Montgomerie who wrote first and best about it in the Times some years ago.

A substantial minority of British voters, to both the right and the left of what we may call the centre, are frankly nuts. They need and deserve nutty parties to vote for. Take the left. It’s a tragedy of our era that voters, activists and a few politicians too who are rank Marxists, not democratic socialists, should have lodged themselves within the Labour party so securely that they now control its leadership. Momentum has nothing to do with the tradition of post-war Labour in government. Can you doubt that British politics would be both cleansed and clarified if these people were to set up their own party and put it before the voters, rather than hijack the mainstream Labour party as they so successfully have?

It is of course possible that if we had both a centrist Labour party and a far-left break-away, the former might to do deals (even form coalitions) with the latter when Labour fell short of an absolute majority. So be it. I would far rather see John McDonnell and Jeremy Corbyn negotiating with (say) an Yvette-Cooper-led Labour government than see these two, as they now are, in the driving seat, and Cooper bound and gagged in the boot.

But if you follow that logic you should examine too its applicability on the other side of the political divide. It’s possible to imagine a sane (if to me disagreeable) version of the sort of Ukip that people like Douglas Carswell, Stuart Wheeler, Suzanne Evans and Nigel Farage (when they all were talking to each other) aspired to create. Now suppose that, despite first-past-the-post, this movement succeeded in capturing enough seats (as Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats did) to hold the balance in a hung Parliament. It could happen: at least a tenth of British voters are really very right-wing, and they cluster in some constituencies.

A more centrist Conservative party might have to do deals with that kind of Ukip in order to form a government. Moderate Tories like me would have to live with it; Remainers would have to, too. Such a government might (for instance) have been forced to hold the European referendum that David Cameron was anyway pushed into calling. But this would have been transactional, and openly so; and such transactional politics would probably now be producing a second referendum, just as the Ukip threat produced the first.

Instead, and as we do our politics today, a huge issue is forced beneath the surface like an abscess. Our Conservative party has been poisoned by minority internal Brexiteer agitation into fouling its own electoral nest. We have ended up with an embattled Prime Minister whose heart may never have been in the Brexit stuff, while a gang of zealots threaten to bring the pillars down within the Tory temple, all the while mouthing loyalty to the Conservative party. ‘Why don’t you join Ukip?’ If only that could become, again, a sensible question.

Comments