Political cultures differ. In Iran, for example, hyperbole is expected in all political conversations. So slogans always call for ‘Death to the US’, and nothing less. In Britain, of course, the use of language is more even-tempered, but other rules apply. Blaming the civil service for failure is considered OK, but charging an individual official, even a Permanent Secretary, for the same is considered off-limits. If a minister were to try it, then he’d be accused of trying to pass the buck on towards defenceless officials.

But, as Camilla Cavendish points out in today’s Times (£), failure is often also the fault

of senior officials who, despite problems in the past, move seamlessly from job to job and from Department to Department. Many hoped the coalition would find a way to deal with this. Remember the

talk about permanent secretaries bidding for jobs by showcasing their plans? Or the idea that MPs would be given very specific jobs, rather than organisational briefs? Or the talk of adopting a New

Zealand-style ‘beehive’ model with ministers located outside of their Departments and civil servants coming to them at a central location for meetings?

The government has not done anything like this sort of radical shakeup, nor looked for ways to ensure that officials, alongside ministers, take responsibility for delivery. There are four reasons,

I reckon, which are worth dwelling on:

1) The coalition’s reliance on officials. Coalition has meant greater reliance on officials, not less. Officials have often been the unofficial go-betweens; hammering out

agreements between the Tories and the Lib Dems. Sub-Cabinet committees that once lay dormant are now taken seriously, and have had to be staffed up.

2) The Werritty factor. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the Werritty case, officials — led by Sir Gus O’Donnell, the outgoing Cabinet Secretary — have used it

to re-assert their power over ministers and advisers, by tightening access and controlling what minsters can and can’t do to a greater degree than before. The post-Werrity style of government has

given more power to officials, not elected ministers.

3) A mistaken diagnosis of the problems of Tony Blair’s government. Labour did not fail because its leader sat with a few friends around the sofa in the No10 den. And,

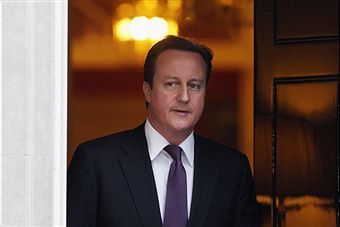

similarly, if David Cameron fails it also won’t be because he makes decisions with a tight, small group of friends and confidantes. That’s just the way government works. But by pretending

this was Labour‘s greatest failing, the Tories set themselves up for a cull of special advisers, which again gave officials more power. Though the number of SpAds seems to have grown since,

in part to make the Lib Dems happier, the damage was done.

4) Establishment thinking. The Prime Minster and his close advisers can be, well, quite Establishment in their thinking. In many cases they tend to share the views and instincts of

senior officials and, on a range of issues, they do not challenge them enough. Some ministers and advisers break this mould: Ian Duncan Smith, Michael Gove and Steve Hilton spring to mind. But they

are, sadly, the exceptions. So, once again, officials accrue more power.

As understandable as some of this may be, it’s still a problem. If the coalition does not push for a rebalancing of power between unelected officials, elected ministers and their mandated advisers, large-scale reform of the British machinery of government may never happen. And that means country-wide reforms may be stalled too.

Comments