Yet another sign that we are living in very strange times: a pair of celebrities, their names made by TV, have switched over to radio for their next project. Not starring in their own series on BBC2 or Channel 4, but on a medium that could have become redundant yet is refusing to give way (the latest Rajar figures indicated that listening is on the up across all networks). Plenty of stars made by radio have gone on to household-name status on TV (Steve Coogan, David Mitchell, Chris Morris). But Eric Monkman and Bobby Seagull, who began trending on Twitter because of their appearances on BBC2’s University Challenge — Monkman, the geek with his razor-sharp eagerness to get on the button; Seagull, the cool, smiley guy — are now starring on Radio 4 in their own show.

Monkman and Seagull’s Polymathic Adventures is not quite Little and Large but an astute commissioner recognised their double-act potential and that it depended not on their differing appearances and manner but their verbal dexterity and complementary voices. In this one-off (a series beckons) they set out to find out why it’s so unfashionable to know a lot about very different areas of knowledge, often obscure (like stained glass) and usually very precise (Davis Cup tennis). Why is there now such a gulf of incomprehension between literature and science? Why are we so suspicious of ‘experts’ when the most significant discoveries are only made when people do spend years and years of their lives focused on just one thing? What happened to the Renaissance man, or woman, as knowledgeable about what heaven means as about what you might find in the heavens?

Monkman and Seagull were in opposing teams on University Challenge but on air they worked together, both equally at ease meeting scientists, historians, Stephen Fry, each quite different in style of approach and tone yet on the same mission: to work out how know-alls can contribute to society, concerned that their obsession with finding out stuff might inhibit their usefulness. They reckoned that ‘the last man who knew everything’ was Thomas Young, who died in 1829. He taught himself 400 languages, began to crack the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone, trained in medicine but also understood physics. Even then he was criticised for ‘dabbling’ in too many discrete areas of knowledge.

This week, as if in response to their concern that we’re not curious enough, the World Service has given us three programmes about space, with a new series on Stargazing led by Dava Sobel (author of Longitude) and a couple about the Voyager missions and the Cassini-Huygens mission. Space 1977 took us to an unremarkable building on the outskirts of Pasadena in California, which each and every day witnesses something extraordinary — messages received from outer space. It’s the home of the Voyager space missions, which since they were launched in August and September 1977 to explore outer space have been travelling further and further beyond the limits of our imagination — tiny spacecraft travelling at 38,000 miles an hour powered by computers made 40 years ago. The smartphone in your pocket, we discovered, has 240,000 times more memory.

The computer on board Voyager 1 uses just 12 watts (or the same kind of power used by a light bulb in a fridge) to transmit its data back to base, taking 38 hours, from way beyond the reaches of Saturn, Uranus and even Neptune — and it’s been working continuously all those years. Why, then, do our own household computers have a shelf-life of only about five years?

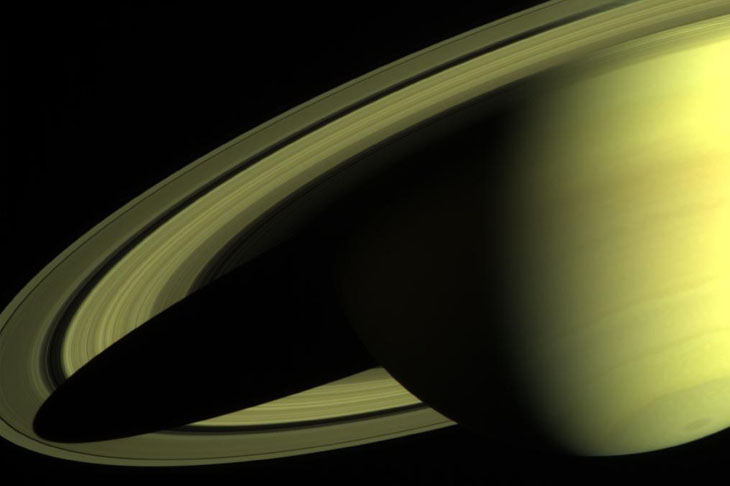

Perhaps a more extraordinary story was revealed in this week’s documentary, Cassini’s Last Adventure, about the space mission to Saturn. Cassini has been orbiting the planet since 2004, taking seven years to reach its destination. From it the Huygens probe was landed on one of the planet’s moons, Titan, sending back information to planet Earth about this far-distant sphere. What it’s given us is the realisation that other planets have similar geology to us, with riverbeds, rounded pebbles, sand dunes. We’re not unique. But on 15 September the mission will be brought to an end, Cassini programmed to enter Saturn’s atmosphere, where it will be consumed by the gaseous heat, to prevent it contaminating this virgin space with man-made materials.

Stargazing, meanwhile, told us about the Polish astronomer Copernicus, who without the benefit of telescopes and purely from hours of studying the night sky realised that the sun rather than Earth was at the hub of the universe and that the Earth moved. He understood the shape of our planet by seeing its shadow projected on to the moon during lunar eclipses, but didn’t dare to publish what he knew until just before his death in 1543, knowing that his assertions that we on Earth were no longer the centre of everything were too shocking to be accepted just then. Even now it’s a bit discomfiting to hear scientists talking about walking across the surface of Titan as if it were like being on the Côte d’Azur.

Comments