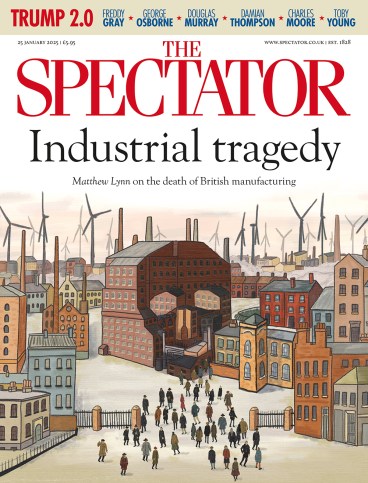

The French sociologist Alain Touraine coined the term ‘post-industrial society’ in 1969. By the 1980s it had become shorthand for the kind of services-based, individualistic economies most major developed nations had created. Today, the UK is moving its economy beyond that. We are creating what might be called a ‘zero-industrial society’. Climate change targets, soaring energy prices and rising taxes on employment are killing off Britain’s small and vibrant industrial base.

Last week, Ineos closed its ethanol plant in Grangemouth, Scotland, with its chairman Sir Jim Ratcliffe warning of ‘the extinction of our major industries’. The previous month, Airbus announced it was cutting 500 jobs. In October, JCB cut 230 jobs; in July Dyson said it was cutting a third of its British workforce. These companies are examples of brilliantly successful British manufacturers with a global presence. If they can’t make things here, what hope is there for less successful rivals? In recent months, Vauxhall has closed British plants and the steelworks at Port Talbot have been consigned to history, as has the appliance maker Hotpoint, which shut a factory in Bristol in October, leaving a century of history behind.

Do we want to embrace deindustrialisation as a consequence of net zero?

British manufacturing, which had been broadly stable at around 8 per cent of GDP, faces a full-scale collapse. Worse still, Keir Starmer’s government, for all its talk of an ‘industrial strategy’ and of creating the fastest-growing economy in the G7, appears to be doing everything it can to eliminate manufacturing as completely as possible.

The figures make for sobering reading. The output of the chemicals industry is down 38 per cent since 2021. Cement manufacturing is down 40 per cent over the same period, electrical equipment down 50 per cent. Overall industrial output is down by 10 per cent since the pandemic. Make UK, the trade body for the manufacturing industry, recently revealed that the UK has, for the first time, dropped out of the top ten countries for making stuff. We have fallen behind Mexico, which has been helped by a wave of Chinese investment looking for ways into the US market, and even by Russia, which moved up to eighth spot globally, helped by Vladimir Putin’s outlay on arms. With total manufacturing output worth $259 billion, we have also fallen behind Italy ($283 billion) and France ($265 billion). Of all the major countries, we are deindustrialising most rapidly.

This is part of a wider trend of the UK becoming a net debtor nation: we do not sell enough goods and services to the rest of the world to keep afloat. The result? We have to tolerate mass foreign ownership of British housing stock, bonds, equities and debt.

The determination of successive parties to be the global leader in hitting net zero has taken a huge toll on our industrial base. Even by 2021, industrial electricity prices were 38 per cent higher in Britain than in France and 159 per cent higher than in the US. The gap has since widened. Instead of fixing that, we are adding extra levies on top. Cornwall Insight reported last month that the standing charges for industrial electricity had risen sixfold since 2018. In some industries like cement, energy accounts for between 50 per cent and 60 per cent of the total production costs. These bills are crippling.

It is not just electricity prices. The determination to only manufacture ‘green steel’ has seen plants such as Port Talbot close. The quotas for electric vehicles, meanwhile, have forced car-makers to stop making petrol cars. At the same time, we have been refusing new licences to develop North Sea oil and gas, and loading extra charges on the few remaining fields. The irony is that we import energy-intensive and high-emission products and vast amounts of gas. The green commissars in charge of hitting our net-zero targets don’t care: all that matters is that our hands are unsullied by anything that contributes to climate change. There were meant to be lots of ‘well-paid green jobs’ to replace all the traditional industries that were closed down, but there’s very little evidence of them.

Do we want to embrace deindustrialisation as an implicit and necessary consequence of our environmental policy? If so, our politicians should come clean and say so. This week, France’s foreign minister was candid about the effect of green policies on France’s economic outlook. ‘The ecological transition is the main priority,’ Eric Lombard said. ‘We have to adapt and this requires a lot of investment, which is not always profitable, and this risks leading, and we have to accept it, to a drop in the profitability of companies in the medium term.’ No British politician has been this honest.

There are other factors behind Britain’s rapid deindustrialisation. Our creaking planning system means it’s virtually impossible to expand (or alter) a factory once it’s built. If you need a new one, which might be more efficient, you can forget about it. In November, Wakefield Council refused an application from The Sleep Factory to extend its plant making high-end mattresses after local residents objected to the extra lorries potentially clogging up the roads. Meanwhile, we have loaded more and more costs on to employment with the increase in national insurance charges that employers pay. We now have one of the highest minimum wages in the world as well. Britain has become an expensive place to employ people.

The decline of traditional heavy manufacturing in the 1980s may have convinced some policymakers that making stuff no longer mattered, and that the future lay in services and technology. But it’s not shipyards and car factories, which never had a hope of competing with the Koreans and the Chinese and were hooked on subsidies to keep them alive, that are closing down. It is those niche, sophisticated manufacturers serving global markets and generating much wealth.

Manufacturing contributes the most to growing productivity. It is a lot easier, after all, to use robots and AI to boost output at a pharmaceuticals plant than it is for a law firm or an advertising agency to increase output. Manufacturing takes tech innovations, applies capital to it and generates improved output per hour worked.

Manufacturing and tech go hand in hand. Trump understands this: as one of his first acts this week he announced a $500 billion investment in building AI data centres, which will create 100,000 jobs.

In 2005, Britain’s productivity growth started to fall off a cliff. It never recovered from the 2008 financial crash, which damaged overall economic activity, liquidity, risk-taking and investment. The country’s underlying deindustrialisation helped turbocharge this decline.

As we continue on the path of destroying our manufacturing industries, we will not only lose the 8 per cent of GDP that it contributes – although that will be catastrophic in itself. We will also lose the skills and technology that go with it. One consequence will be greater widening inequality: manufacturing industries are disproportionately concentrated outside the south-east. Losing more productive jobs from elsewhere in the country further widens the regional divide. Manufacturing jobs pay 12 per cent more than the UK average, controlling for qualifications, experience and seniority. They provide lots of well-paid employment, especially for the kind of blue-collar skilled manual (and often mostly male) workers who tend to struggle in a female-dominated services economy.

Manufacturing also powers exports, generating foreign currency and keeping the trade balance from sinking too deeply into the red. Brexit saw a small initial uptick in manufacturing as companies sought to reshore to avoid trade barriers with the EU’s single market, but this hasn’t lasted, due to energy cost-driven industrial collapse.

There is a risk, too, that our manufacturing decline could harm national security. Yes, efficient global supply chains may keep prices low for consumers and businesses. But there are wider policy objectives at stake, such as the UK not being too dependent on China in the event of a global conflict, should Xi Jinping decide to invade Taiwan.

The UK stopped being a mass manufacturing nation four decades ago, and rightly so. Many traditional industries were no longer competitive on global markets, and could not hope to be. Yet we maintained a niche in high-end production. Right now, we are wiping out the factories that remain. By the time this government has finished, they may well be completely destroyed. By then it will be far too late to do anything to save them.

Matthew discussed the decline of Britain's industry further alongside the trade unionist Paul Nowak, and The Spectator's Lara Prendergast and William Moore, on the latest Edition podcast:

Comments