Inspired by Darwin’s bicentenary, Scott Payton explores the collectors’ market for historic scientific instruments

As the world celebrates the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth, and as awareness of climate change continues to rise, interest in the natural sciences is soaring. This is rubbing off on the collectors’ market in scientific instruments, with globes, sundials and microscopes proving particularly popular.

The appeal of globes is especially broad — because they are scientific instruments, decorative objects and comprehensive cartographical histories wrapped into a single package, says George Glazer, a former attorney who now runs a globe dealership on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (www.georgeglazer.com). ‘You could argue that a globe is the ultimate item to own, because it is so many things in one,’ he says.

Prices for antique globes range from less than $500 for smaller 1930s models to as much as $2 million for rare 16th-century specimens. ‘For a pair of high-quality early 19th-century English floor globes in very good condition, you’re looking at $200,000 to $250,000,’ says Glazer. Floor globes, rather than those designed to sit on a table, generate the most interest. ‘They tend to sell the best because they fit the concept of a globe that people have in their mind, which they might have picked up from a movie or a visit to a library.’

Globes are also sound investments. Prices for floor globes doubled between 2000 and 2008 — with the value of some 1940s and 1950s ‘black ocean’ globes tripling over this period. This is a reflection of a recent rise in interest in modernism and 20th-century decorative arts in general, Glazer says. ‘Twenty or 30 years ago, this kind of thing was considered junk. I’d certainly rather have my money invested in my inventory of globes than in company stock at the moment.’

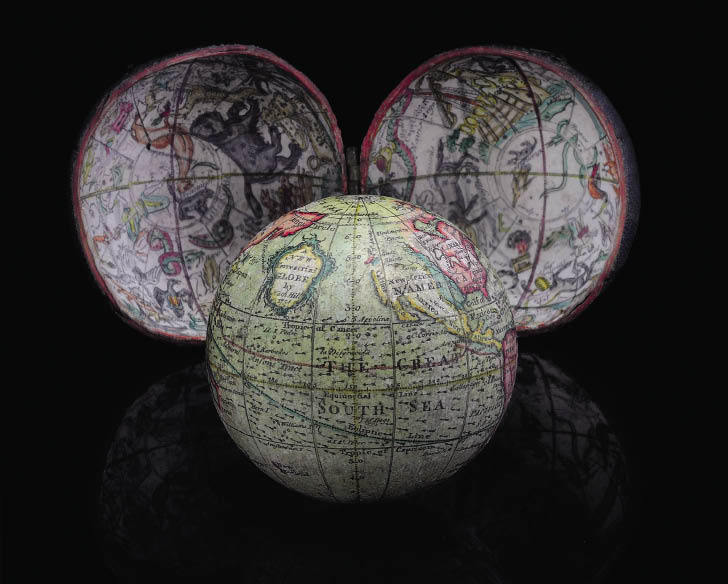

Christie’s South Kensington sells globes at its biannual travel, science and natural history auctions. James Hyslop, the auction house’s scientific instruments and globes specialist, says that tiny pocket globes (see picture) are proving even more popular than many larger models. ‘They were created in the 18th and 19th centuries, predominantly by English makers. Prices for these have shot up — especially for 18th-century models, which have fetched up to £11,000 at auction.’

Pocket globes tend to be around three inches in diameter, and often come in spherical fish-skin cases decorated with maps and charts on the inside. They are more practical for those interested in building a large collection, simply because they don’t take up as much space as desk or floor globes. As George Glazer says, ‘I don’t know anybody who has a room containing 20 or 40 floor globes — other than me.’

Elsewhere in the scientific instruments market, Islamic items are also ‘shooting up in popularity and value’, thanks to a surge in interest among wealthy buyers in the Middle East, according to Hyslop. ‘The sheer amount of money in the Gulf has really driven up prices. Some Islamic sundials which might have sold for £100 ten years ago are now making up to £4,000.’ Prices for Islamic astrolabes — instruments designed to measure the positions of heavenly bodies — are also rising sharply. ‘The last astrolabic quadrant [a sophisticated type of astrolabe] we sold, which dated from 1876, made £5,500. Ten years ago you could pick that up for £100 quite easily,’ Hyslop says.

Sundials of all vintages, from all over the world, are perennially popular, he adds. ‘You can pick up a good 19th-century sundial for £50, or pay £100,000 for a beautiful Renaissance masterpiece. Prices for sundials from the best 16th- and early 17th-century manufacturers have steadily been increasing, and are starting to look quite strong now.’

Scientific instrument collectors are a patriotic crowd who often pay a premium for items from their own country, Hyslop explains. ‘For example, French private collectors will pay a bit more for a French 17th-century sundial than for an English sundial of equal quality from the same period. And English collectors will pay much more for an English Victorian microscope than for a similar item from the Continent.’

The star lot in Christie’s South Kensington’s next travel, science and natural history sale (which takes place on 8 April) is a silver microscope created by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, the 17th-century ‘father of microbiology’ who was the first scientist to observe muscle fibres, bacteria and sperm-atozoa, thanks to his breakthrough invention. The microscope in the Christie’s sale is one of only nine of its kind known to exist. Christie’s estimates its value at £70,000 to £100,000. ‘It really is a Holy Grail of instrument collecting,’ Hyslop says.

Microscopes sit alongside globes and sundials as the most popular antique scientific instruments, says Rick Blankenhorn, who was a scientist for an aerospace firm before founding Gemmary Antique Scientific Instruments (www.gemmary.com), a dealership in southern California. ‘Microscopes from the early 18th century to around 1880 are always highly desirable — particularly English specimens from the best makers.’

Why are microscopes more popular than other instruments? Blankenhorn explains: ‘They’re beautiful, and everybody understands what they’re for. Surveying instruments attract surveyors. Surgical instruments attract surgeons. But microscopes are collected by a lot of different people.’

What factors determine the value of a microscope? ‘Condition, condition, condition,’ he says. ‘The “Lamborghini” of late Victorian English microscopes is the Powell and Lealand No. 1, created in 1875. A top-quality specimen, with its original case and accessories, will sell for $20,000 or more.’

While the value of antique microscopes remains strong, telescopes have ‘really fallen off during the last ten years,’ says Hyslop — but this means that there are bargains to be found for those still keen to collect. Graham Marsh, owner of the Lancashire-based dealer Antique & Scientific Instruments UK (www.asiuk.net), says that Old Telescopes by Reginald Cheetham is an invaluable research work for those new to the area — though finding a copy might require quite a bit of hunting.

Scientific instruments in general are attracting an increasingly varied breed of buyer, Hyslop says. ‘Traditionally, collectors tended to be retired doctors and engineers — mostly men. But the majority of instrument curators in the UK and the US are now women, and we’re seeing the number of female collectors increase.’

He has the following advice for those thinking about starting their own collection: ‘It’s really worth coming along to auction views and using the instruments yourself. Find out what you can see through a 19th-century microscope. Then you’ll be able to appreciate it as a practical object as well as a beautiful work of art.’

Comments