We might be twins, Catherine Taylor and I. We were both girls growing up in Yorkshire in the same decades – I in the West Riding (where an alley is a ‘ginnel’), her in the south (where it’s a ‘gennel’). We are children of the Yorkshire Ripper years, conditioned to be constantly scared of the murderer, the dark, and our independence. We were both fatherless too young – mine dead, hers departed to another household; and we both had strong mothers keeping the remaining family afloat and forced to take in lodgers – in our case, Polish, German and French, in hers, Japanese and Senegalese. Much of this bookis familiar – but not all of it. There is still room for surprise and stirring.

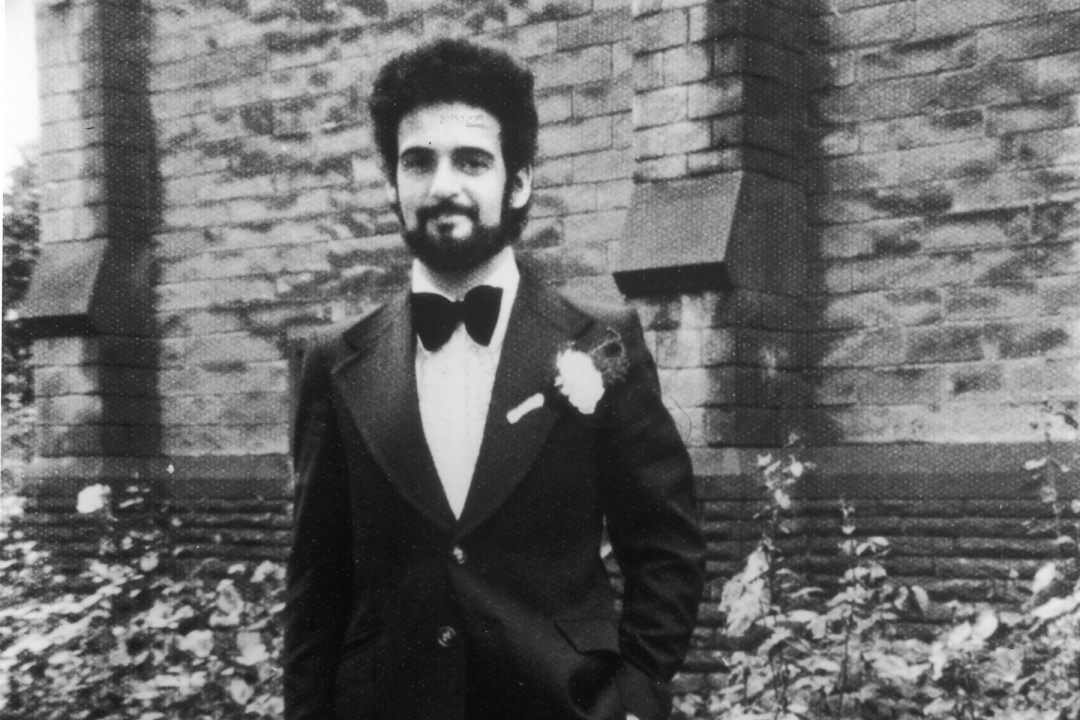

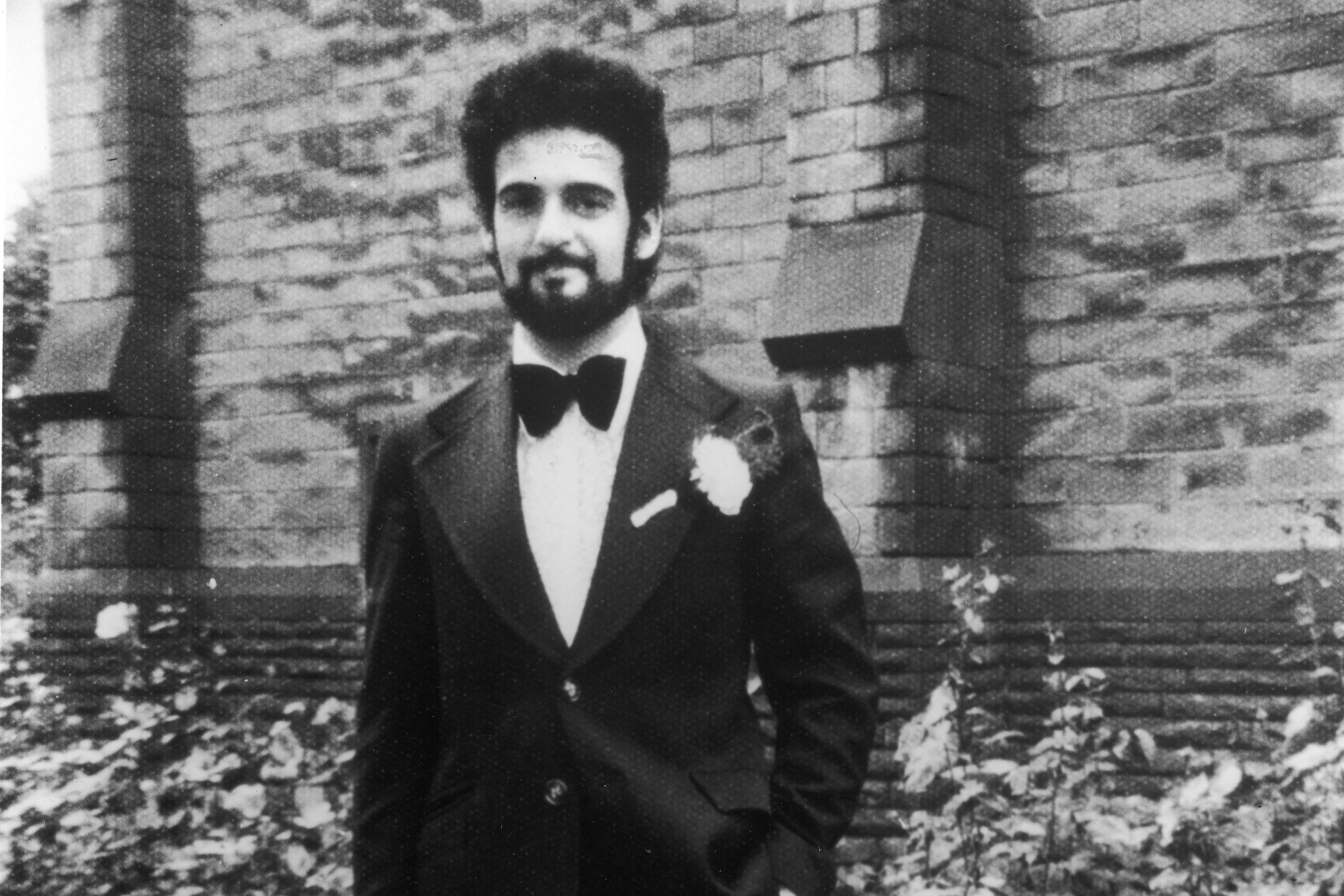

Its title derives from the Sheffield Outrages known locally as ‘The Stirrings’, a period in the mid-19th century when aggrieved trade unionsts murdered and bombed. Taylor duly writes of violence – of Peter Sutcliffe, the Battle of Orgreave, the Hillsborough disaster and the quiet Cold War terror of the Bomb, although this is usually at a remove and oddly passive. She sometimes calls events ‘an uneasy backdrop’ – and that is what they were, no matter that she was living through them. The NUM is based in Sheffield, where she grew up, but she watched the Battle of Orgreave and the tragedy at Hillsborough on the news like everyone else.

This muted tone can be powerful: the departure of Taylor’s father is vivid because dampened, the mutism conveying her childish inability to express her distress. She sees one lodger, Henriette, a Senegalese woman, extravagant in her outward grief at the death of her mother and marvels at it. To describe her own feelings she has to reach for a bird, remembering a starling trapped in a chimney which resisted help in its fright: ‘The moment the frantic flapping ceased was even worse than the pitiful sound of invisible agitated wings inside the chimney breast.’ When she discovers a letter her mother is writing and realises that her father was leaving them, ‘it felt as if that starling were trapped in my body’. Gradually her father recedes, until she finds herself getting into a stranger’s car every second Saturday, exactly what she’s not supposed to do, except the stranger is her father. ‘Schrödinger’s Dad, half dead, half alive.’

Her slow understanding of what it means to be a young woman, to be careful and ‘frit’ of men, is also well done. Every woman and girl will recognise this. On a train as a teen-ager, quietly reading her book, she is harassed by a passenger and the conductor, both male, and hides in the toilet. At a party she wears a pretty dress and feels beautiful, until an older man tells her: ‘‘‘Soon you’ll be able to have any man you want”… after admiring the dress and staring for too long at the neckline.’

Some of life’s landmarks – first bra, first period – are efficiently but not memorably conveyed. Others are startling, such as her account of the abortion she had in a women’s hospital in Cardiff – ‘a low-level building of red brick, with tall, stiff, angry lupins standing to attention in well-ordered flowerbeds. No question of anything out of control here.’ Relieved of the foetus, she goes for a shower: ‘I noticed a small pool of fresh blood on the floor as I entered the cubicle. I stepped over it. It wasn’t mine.’ She identifies with Europa of myth, ‘being herself, daydreaming, picking flowers’ when she is raped by Zeus; and with Cassandra, cursed with the gift of prophecy and murdered by Clytemnestra. ‘Cassandra foretold her fate, of course; she smelled blood.’

Taylor’s greatest stirring comes from inside her. Her ‘nice little goitre’, her butterfly-shaped thyroid gland, goes awry in her late teens, leaving her exhausted and ravenously hungry to the point of putting on five stone in a year, a trauma for anyone. But even after the shamefully late diagnosis of Grave’s disease, the drugs don’t work, so that in ‘early May… the garden wall was warm to the touch once more. I was in hospital. Tomorrow I would be having my throat cut.’ She nearly dies from an allergic reaction to the anaesthetic and her thyroid is mostly excised.

The Stirrings essentially halts after her university years in Cardiff with a tragedy in her shared house, which is when adulthood truly begins. We leave Taylor in London, in a relationship, with different stirrings – ones that all women perpetually navigate in a way that men never quite comprehend. She was only picking flowers.

Comments