Any seasoned opera-goer is likely to have had the experience of attending a performance where most things are right, but the overall impression is dismal; and also where, even more puzzlingly, most things are wrong but somehow the total effect is good or even overwhelming. To some extent it is relative to the work being performed, but not entirely; and to a much greater extent it depends on what your expectations are — I always try to have low ones, but expectations aren’t voluntary, alas.

Last Sunday’s performance of Tristan und Isolde at the Royal Festival Hall was, emphatically, the second kind of occasion. It’s not hard to list what was wrong with it, and that will sound damning. But it was nonetheless a shattering experience for me and I think for many of the audience who found as much to be annoyed by as I did. Tristan is likely to be shattering, of course, the power of Wagner’s genius triumphing over the inadequacy or perversity of interpreters; yet the last two productions at the Royal Opera have shown how decisively it can be undermined by presumption from the director and inadequacies in casting and/or conducting.

This semi-staged affair at the Festival Hall has been doing the European rounds for the past five years, and concluded here. The main novelty was a continuous visual commentary, sometimes mobile, sometimes static, projected on a large screen behind the orchestra. The visual artist was Bill Viola, the ‘artistic collaborator’ Peter Sellars. That sounds like trouble, and it was. The images ranged from the fatuous to the gross. The first was of waves, obvious enough if hardly required: Wagner’s music is powerfully suggestive.

Then a male and female figure loomed, and we saw their inexpressive faces and then their bodies. The man started fiddling with his trousers and soon both were naked (hence this was a show for over-14s). They stood thus exposed and then buried their heads in bowls of water — a rite of purification. The snag is that this was happening while Isolde was railing at Tristan and everything else; irrelevance and banality made concentration on the electrifying drama of Act I quite difficult.

There was a fair amount of intelligently involving use of the whole auditorium: Tristan and Kurwenal were standing in the side upper stalls for the exchange with Brangäne; the sailors’ chorus and the trumpets at the end of Act I were somewhere behind me, and gave the conductor a chance for flamboyant mobility. Brangäne sang her watch song from the topmost box; and so on. The visuals for Act II began with torches searching for something in a dark forest, B-movie stuff. Later on, fire and water were the main ingredients, relatively harmless. At the end, the dead video-Tristan levitated, bubble-surrounded, through water and disappeared from sight.

Meanwhile, on stage we had the best all-round group of singers I have seen for a long time. Violeta Urmana, the ranking Isolde, improves all the time, and if she doesn’t have much variety of tone or manner, and is rather short-breathed, she is tireless and committed. The Tristan of Gary Lehman is a major discovery: he, too, lacks sensuous beauty of voice, but he has everything else, and didn’t spare himself in the least in the first two acts; while in Act III, on his bench, he lived his part to a degree that would have been almost intolerable if the orchestral accompaniment had been more searching.

Esa-Pekka Salonen strikes me as a cold and mannered conductor. The start of the prelude was so slow as to be inert, the close sank to an inordinately prolonged silence. In between, what should be music’s most prolonged climax was segmented into a series of mini-climaxes reminiscent of Solti; and the same was true of the whole work. The Philharmonia played wonderfully, but they weren’t often asked to do the right things; and never anything freshly revealing. The supporting singers were all adequate, and Matthew Best’s King Mark was great singing and great interpretation. So, despite all the irritations, the evening amounted mysteriously to an unforgettable event, one I shall reflect on for a long time

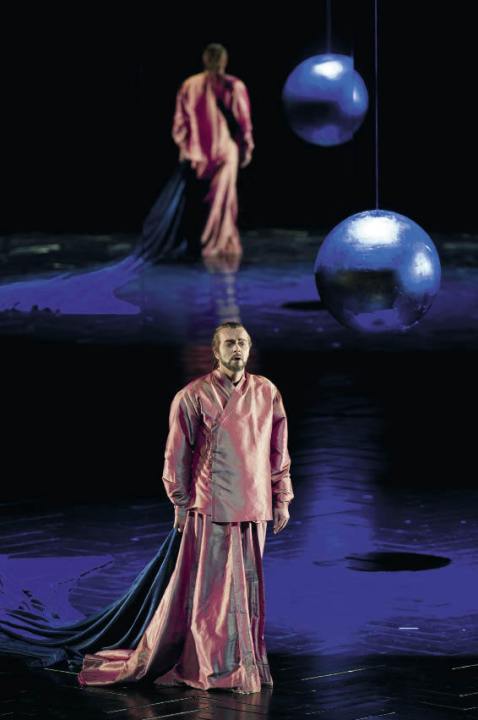

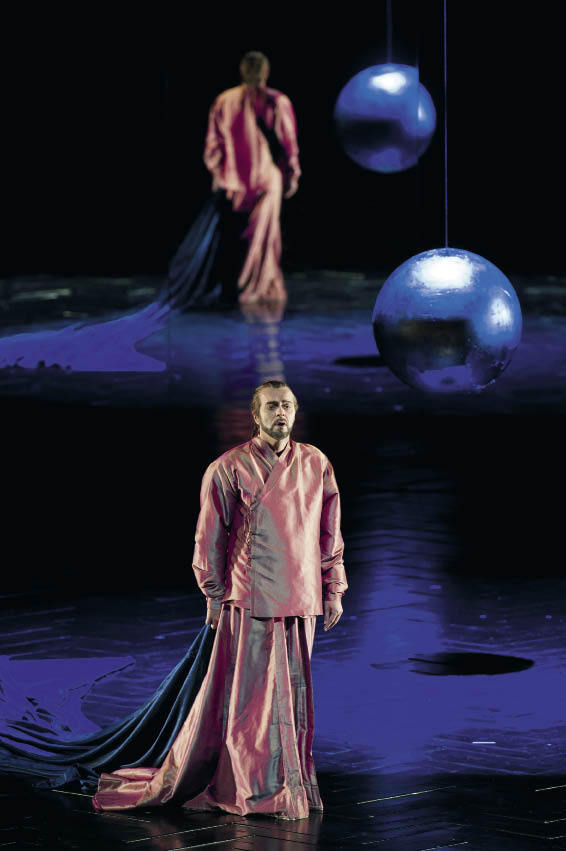

No mysteries surround the Royal Opera’s Niobe, Regina di Tebe by Agostino Steffani, except why on earth anyone thought it worth doing. Great composers such as Lully and Rameau remain mainly unperformed, certainly in London’s main houses, while this prolix baroque triviality gets a fairly lavish outing with some star singers. There are people, I realise, who revel in the sound of baroque, even when it consists of marathons of recitative and only brief arias, mainly sung by counter-tenors or male sopranos. The Polish Jacek Laszczkowski had the best music, and though I dislike his voice he sang imposingly. Véronique Gens, a marvellous artist, had less to do and made a muted effect. The plot is mindlessly, meaninglessly complicated, but there is so much of it that this piece has to last ages to get through it all. I don’t foresee a Steffani revival.

Comments