If no-one was very excited about the launch of the Lib Dem’s election poster this morning, it wasn’t just because of the rain.

According to The Times, political posters are on their way out. Political parties are spending 50 per cent less on outdoor posters this year than they did in 2010, and unofficial reports have suggested that the Conservatives’ spending on outdoor ads is yet to hit seven figures. By the end of March 2010, the Tories had already splashed out over £3 million.

No doubt the barrenness of Britain’s billboards is partly the result of a lack of funds, but it’s also a conscious choice based on the belief that social media will win the election by reaching my undecided generation.

It’s true that the internet is changing politics. President Obama’s 2012 Twitter Q&A on the fiscal cliff crisis was a social media masterclass. From the ‘hey guys – this is Barack’ to the serious answers to voters’ concerns, Obama showed what Twitter can do for democracy: it makes our representatives less remote and more accountable.

But in their obsession with appearing in-touch, politicians have forgotten that there are some things a billboard can say that a tweet just can’t. Social media is great for democracy, but does nothing for leadership: it allows voters to get quick responses to specific concerns, but in the process makes it harder for prime-ministerial candidates to present a clear vision for Britain.

My generation might not like politics, but we do like political posters – there’s no teenage room decoration more clichéd than a print of Che Guevara. Soviet propaganda posters are similarly popular, and the appeal of works like the iconic ‘Motherland calls!’ is clear: as a peasant woman draped in red beckons you to fight in the Second World War, it’s not hard to see what the Soviet dream was all about and why it was supposed to be worth fighting for.

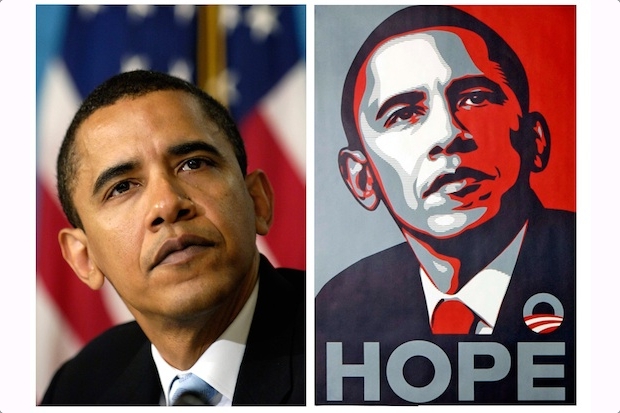

Powerful posters needn’t be the monopoly of extremists: what drew 2008’s young swing voters to Obama was not the tweets, but the Hope poster. Social media campaigns might motivate the keen youngsters who already follow politicians to hit the streets, but an outdoor ad is democratic in a different way: it’s seen by everyone, whether they’re looking for it or not.

Of course, political posters only work if they’re done right: no-one is going to be inspired to cast a ballot by a vast portrait of David Cameron alongside some platitudes about protecting the NHS. Indeed, such ads don’t work because they represent the Twitterification of our billboards: a personal photo, alongside a very specific promise designed to chime with voters’ self-interest.

David Cameron and Ed Miliband are wrong to consider outdoor ads relics of the pre-internet age. Voters want a vision, and there are few more powerful or accessible ways to show what you stand for than on a poster.

Comments