A Sunday morning in Bethnal Green and Adam, who has been leading Kray-themed walking tours of the neighbourhood for almost two decades, corrals a congregation of eight polite, reserved, attentive customers who, with sensible rucksacks, floor-length M&S skirts, reusable water bottles and neutral-coloured, thin-laced trainers, look as far removed from pool hall brawls and basement flat stabbings as it’s possible to get without joining the Church Army or taking up cribbage.

When he started giving tours of the Kray twins’ haunts, Adam tells us, it was impossible to go more than five minutes without some tipsy ageing derelict lurching out of the Blind Beggar pub to inform the group that he ‘knew the Krays personally’. That generation has now mostly been knocked out permanently by the knuckleduster of fatality. But the fascination with the Krays, and other elements of London’s violent past, continues to spread like a black eye after a rabbit punch.

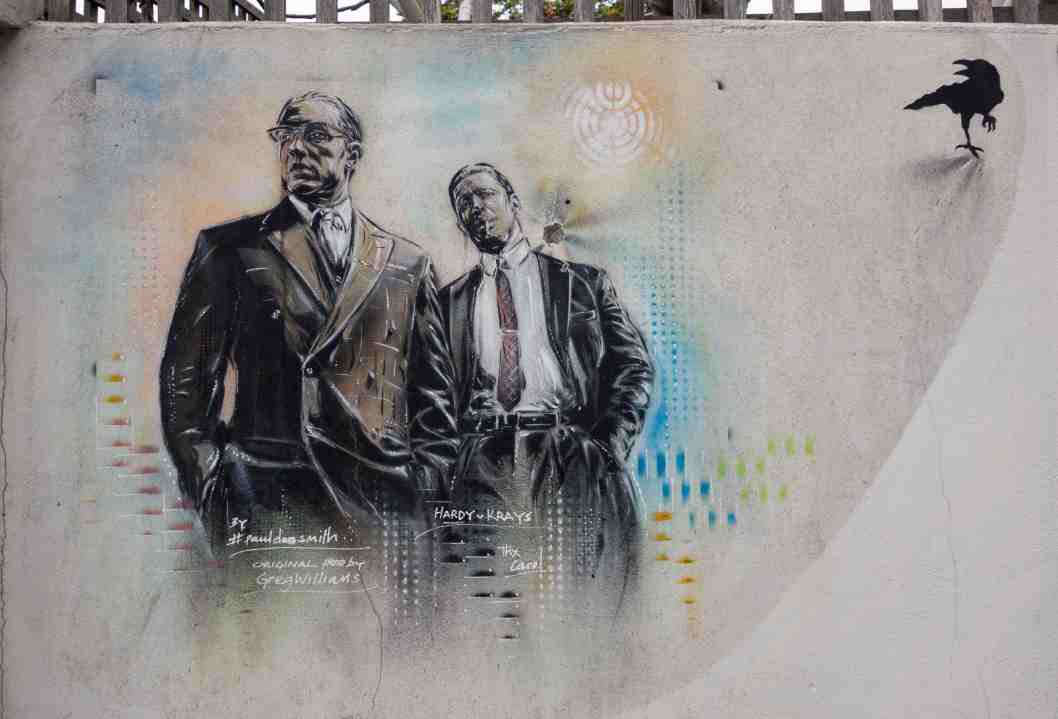

Walking tours are far from the only way to gain an insight into Ronnie and Reggie’s journey from Vallance Road, Bethnal Green in the 1930s Depression to the running of a criminal mob specialising in protection, racketeering and, eventually, murder. You can watch the Tom Hardy film Legend, read the definitive account of their lives in journalist John Pearson’s Profession of Violence or, if you like your brutality mixed with early 1980s synth-pop, watch the 1990 movie biography where Ron and Reg were played by the brothers from Spandau Ballet. Consume the lot and you’ll be further than ever from the truth – which is that the Krays were spectacularly useless gangsters.

But does it matter to my walking tour group that no gang could possibly function effectively when the co-leader was willing to carry out executions himself in front of more than a dozen witnesses? That’s exactly what Ronnie did when he walked into the Blind Beggar pub and shot fellow small-time villain George Cornell in the head. Could a mob really call themselves the ‘kings of London’ when their territory stretched no further than Bethnal Green and a few slot machines in the West End? Would true gangsters allow themselves to be merrily swindled during their prison years by members of the public who knew that one tear-stained epistle about their fictitious child needing surgery would be enough for the brothers to ensure that bundles of bank notes were swiftly dispatched to the purported ‘needy’?

None of this matters. Because nobody really wants it to matter. The two most popular walking tours in London are, and long have been, those dedicated to Jack the Ripper and the Kray brothers. So why are we so fascinated by retro-violence in this city?

Firstly, it could be simply because some of these tours are extremely good. As someone who’s been confused by and fascinated with the Kray twins ever since hearing stories about them in my school playground (located some 200 miles from Bethnal Green and some 20 years after their incarceration), even I discovered plenty from Adam – including that the Krays’ resident parish vicar refused to carry out the ceremonial duties at Reg and his girlfriend’s wedding, telling the gangster: ‘You’re not the marrying kind.’ Perhaps, Adam mused, this wasn’t just a reference to Reggie personality, but also testament to Canon Richard Hetherington’s awareness of Reggie’s sexuality, later confirmed when he came out as bisexual during his three-decade prison term.

These details are certainly of some fringe interest. But our desire to walk in the footsteps of the Krays and other purveyors of mostly seedy, banal violence carried out by seedy, banal men seems to stem from something deeper.

We generally think that we live in violent times and let violence into our own living rooms and laptops far too readily. But actually, there’s less violence on television now than there was in the 1970s, when the likes of The Sweeney showed primetime punching and gouging in a style and quantity that you would never see today before the watershed. So maybe the Krays, Jack the Ripper and all the other yellowing newsprint ne’er-do-wells of yesteryear serve useful purpose for us, whether we sit in their favoured caffs, listen to forensically curated character portraits on podcasts or simply have nicotine-smeared dreams about a vanished London.

The Blind Beggar was, until recently, doing a trade in Ronnie and Reggie-themed burgers and hot dogs (I can’t believe they don’t serve Krayfish)

Not for Brits the muscle-flecked, big business, jury-nobbling, election-swinging, machine-gun-crackling bone-head glamour of US gang violence. We prefer our retro-mobsters to be mates with Barbara Windsor, own snooker halls and eat at greasy spoons. This is the ‘cosy violence’ that so many of us secretly revere, despite knowing it to be as folkloric as Goldilocks or Willy Wonka.

‘Well,’ we reassure ourselves, ‘it all happened so long ago now – times have changed.’ Yes, the times have changed. But we haven’t. How can we if we still get nostalgic over failed gangsters in a tiny neighbourhood of East London six decades on from their brief and fragile reign? Maybe it’s time for us to just admit that we like having the opportunity to play with a two-headed Kray-shaped beast that can no longer bite us back.

The Blind Beggar was, until recently, doing a trade in Ronnie and Reggie-themed burgers and hot dogs (I can’t believe they don’t serve Krayfish) and there is something apt about munching on minced pork or beef in the same room where the murder of George Cornell took place. For what are the Krays if not the burgers of the criminal world? Instantly recognisable, sometimes hard to digest but yet enduringly popular to the middle classes, as long as it’s served in a blinged-up style that all but drowns its humble origins in a slathering of organic sauces and legislated sentimentality.

Of course violence is horrible, bloody, cruel and sociopathic. And organised crime is all of that with a layer of establishment complicity and connivance on top. But we can’t help but admire it. Mainly because the idea of getting everything you want without having to plead, beg, graft or slog for it is tempting. That’s what the Krays give us today. They’re the ultimate in the homegrown variant of vicarious, forbidden desire.

I hear the echo of old Canon Hetherington on my Krays tour: Reggie wasn’t the marrying type in the same way as we’re not the maiming and murdering types. But just as Reggie played at marital convention, we’re playing at being gangsters by wallowing in a bathtub of Kray. Perhaps we should just stop worrying and love the Krays and their myth; one that is by now so polished and worn, so sat on and grooved into a shape that fits our posteriors and our prejudices, that it can’t help but feel comforting.

Give a gangster walking tour of the East End 100 minutes of your life. And it will give you a taste for the kind of violence we find most palatable: a type that comes with a thin collar, a slim tie, a mug of Rosie Lee and an extinction notice around its neck. The Krays are dead. Long live the Reggie veggie burger.

Comments