I was disappointed to read an article in the Times about a new free school in Hammersmith being proposed by Ian Livingstone, one of the founders of the UK games industry. This isn’t because I’m worried about Livingstone’s school luring pupils away from the West London Free School, also in Hammersmith. I’m all in favour of competition. Rather, it’s because Livingstone’s ideas about education are so wrongheaded.

According to the Times, Livingstone believes children should learn through play rather than be subjected to ‘Victorian’ rote learning. In this way, they’ll discover how to ‘solve problems’ and be ‘creative’, instead of being forced to memorise ‘irrelevant’ facts that can be accessed ‘at the click of a mouse’. Exams are dismissed as ‘random memory tests’ and have ‘far more to do with league tables than learning’. On it goes, one cliché after another. Like most people who peddle this progressive snake oil, Livingstone labours under the impression that his ideas are bold and exciting, a radical departure from the status quo. Here he is describing what he thinks of as a typical English classroom: ‘You’re all required to sit still, working as individuals, no team work, no collaboration, no project that can be assessed as a group — all doing the same thing.’

Livingstone has four children, but I can only conclude he educated them all privately, because you’re unlikely to find a single comprehensive that subscribes to this chalk-and-talk model. The approach he promotes as revolutionary — child-centred, emphasis on collaboration rather than competition — has been the norm in our public education system since the 1960s. It’s signed up to by the vast majority of teachers, and until recently any school departing from this orthodoxy was likely to be punished by Ofsted.

Without knowing it, Livingstone is fighting a war that dates back to the 18th century and which his side has already won. His assertion that rote learning snuffs out children’s ‘creativity’ is a common trope of Romantic literature, from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile (1762) onwards. This point of view is neatly summed up in the following lines from ‘The Schoolboy’, one of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence: ‘How can the bird that is born for joy/ Sit in a cage and sing?’

These Romantic ideas about how to unleash children’s inner creative genius have never been subjected to any rigorous, evidence-based analysis, yet they’re now universally accepted by the educational establishment both here and in America. The effect on our public education systems has been disastrous. Many English schoolchildren acquire neither factual knowledge nor the higher-order thinking skills that Livingstone approves of, with roughly a fifth leaving school functionally illiterate and innumerate. As the progressive approach has become more and more ubiquitous, British and American schools have plummeted in the international league tables, eclipsed by countries like China, Singapore and South Korea which still favour traditional teaching methods.

Not only has the influence of progressive educationalists placed American and British schoolchildren at a competitive disadvantage on the world stage, it has also increased in-equality in both countries. One of the great ironies of this debate is that nearly all the advocates of progressive education are on the left, yet the approach they recommend as more ‘inclusive’ and ‘fair’ has ended up entrenching poverty and preserving privilege. The reason for this is obvious: if ordinary children are learning very little at school, they’re never going to be able to compete with those from more affluent backgrounds when it comes to securing places at good universities and footholds in lucrative careers. As the American educationalist E.D. Hirsch says, Romantic anti-intellectualism is a luxury of the merchant class that the poor cannot afford.

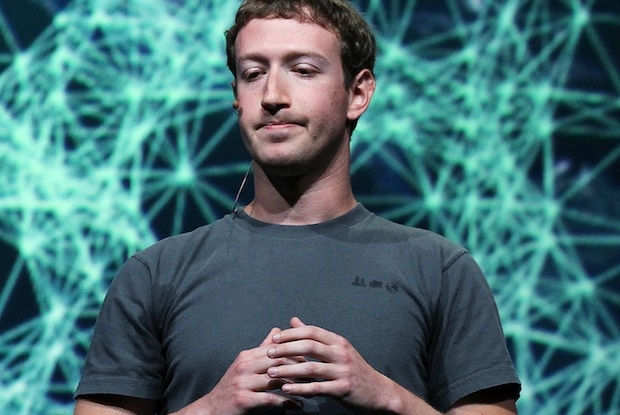

I’m sure Ian Livingstone means well. Wanting English schoolchildren to contribute more to the digital economy is a laudable aim. But all the evidence from cognitive science is that in order to think creatively, children first need to commit a vast array of facts to their long-term memories. Processes like reasoning and problem-solving are inextricably bound up with factual knowledge and cannot be taught separately, with the job of memory being outsourced to Google. In a separate interview in the Sunday Times, Livingstone says he wants children at his school to aspire to be Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook founder, overlooking the fact that Zuckerberg studied Latin until the age of 18. If Livingstone wants to spawn a generation of creative geniuses, he should forget about game-based learning and make Latin compulsory.

Comments