At 7.53 a.m. on Tuesday 30 April 1975, 50 years ago today, Sergeant Juan Valdez boarded a Sea Knight helicopter sent from aircraft carrier USS Midway that had landed a few minutes earlier on the roof of the US embassy in Saigon. He was the last US soldier to be evacuated from Vietnam. As he scurried to the rooftop, he was aware that some 420 Vietnamese, who had been promised evacuation, were left in the courtyard below. They faced an uncertain fate.

The day before it had been reported to Washington that Saigon Airport was under persistent rocket attack. Escape by airplane became impossible. President Gerald Ford explained: ‘The military situation deteriorated rapidly. I therefore ordered the evacuation of all American personnel remaining in Vietnam’.

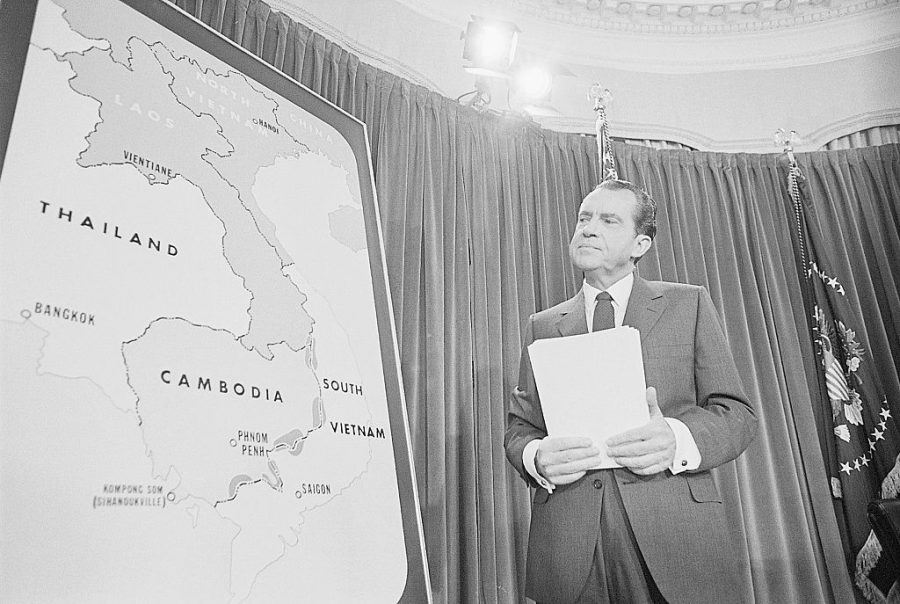

Eventually Nixon bombed the north to the peace table

Back in New York, President Nixon’s Secretary of State was not a happy man. A crestfallen Henry Kissinger cancelled his tickets to see Noel Coward’s play, Present Laughter. Kissinger would note:

For the first time in the post-war period America abandoned to eventual Communist rule friendly people who had relied on us…[it] ushered in a period of American humiliation.

How had it come to this? Just six years earlier the US Army had imposed a crushing military defeat on North Vietnam.

Following the rise to power of the Soviet faction in the North Vietnamese politburo led by Le Duan, General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist party, it acceded to the Kremlin’s demand for a rapid military victory. The resulting Tet Offensive started on New Year’s Eve 1968. In South Vietnam, the Viet Cong’s guerilla fighters attacked 38 cities including the capital, Saigon; it was believed that this would provoke a general uprising. As usual the left overestimated the appeal of totalitarian socialism.

As the former schoolteacher turned military genius General Giap had warned his political superiors in North Vietnam, the result of the Tet Offensive was a decisive victory for the US. The infrastructure of the Viet Cong in the South, which had previously been built up over decades was smashed. ‘First of all, casualties everywhere were very high, very high,’ complained a senior Viet Cong officer, ‘and the spirt of the soldiers dropped to a low point.’

Defeat of the Viet Cong was compounded by the crushing defeat of the regular People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) at Khe Sanh, the main US military compound near the borders of Laos and North Vietnam.

But Khe Sanh was the secondary target. The historic coast of city of Hue was simultaneously assaulted by ten PAVN divisions. In the suburbs civilians were massacred. A French priest, Father Urbain, was buried alive – a typical North Vietnamese punishment. In another shallow grave, the authorities later found Father Buu Dang and 300 of his parishioners. After a close-run battle, followed in excruciating day by day detail by US television, the Marines managed to bring reinforcements by helicopter to a soccer pitch to relieve the city.

One would have thought that starting his presidency with a war-defining victory would have helped Nixon’s promise of ‘peace with honor’. It didn’t. To the amazement of the North Vietnamese, liberal media in the US managed to spin the Tet Offensive as an American defeat not an American victory. The North Vietnamese were thus encouraged to regroup. It took another three years and another significant US victory in their defeat of the North’s Easter Offensive in the spring of 1972 before America was able to bring about peace.

Eventually Nixon bombed the north to the peace table. Under former presidents J.F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, the US had refrained from bombing Hanoi and the port of Haiphong. By contrast, Nixon’s bombing operations, Linebacker I and II, set out to destroy the North’s infrastructure and succeeded.

At the same time, the US Airforce conducted intensive bombing of the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and Cambodia. By this time, the trail had become a highway flanking South Vietnam’s 1170-mile border. One of the great myths of the Vietnamese War was that the US was fighting a poorly equipped guerilla army. The reality was that the north was supplied with the most advanced Russian equipment brought into Haiphong in the North and Sihanoukville in Cambodia in the South.

By the end of 1972, America had dropped 5 million tons of bombs on North Vietnam and its proxy operations in Laos and Cambodia. This was more than double the tonnage used by the US Airforce in the entirety of the second world war in the European and Pacific theatres.

The bombing worked. So did pressure from the Soviets whose economy was beginning to strain under the demands of defense spending that took up to 40 per cent of its GDP. The Paris Peace Accords were signed on 27 January 1973. I was living in Paris at the time and remembered thinking that the Vietnam War which had dominated the media for all of my teenage years had finally come to an end. How wrong I was. Within two and a half years, American military victory and the Paris Peace Accords turned into humiliating defeat.

The Treaty of Paris was regarded not as a legally binding accord by the North Vietnamese, as was the case in America. For the North it was merely breathing space for them to regroup. Within months, the southern hardliners in North Vietnam’s politburo were calling for another ‘final’ offensive.

North Vietnam began the construction of Corridor 613, a re-worked route for the Ho Chi Minh trail. Unlike the original footpath, the new highway was a robust enough to accommodate 10,000 trucks (including the huge Russian Zils with their six-ton capacity and six-wheel drive) hundreds of tanks and a 3,106 mile fuel line. By the end of the war, the trail through Laos and Cambodia would resemble an elongated colony consisting of repair workshops, factories, hospitals, staging posts and rest camp; with its many offshoots the trail would stretch over 12,500 miles.

Thus provisioned, on 26 December 1974, General Van Tien Dung was able to begin the artillery bombardment of Vietnam’s Phuoc Long Province situated 50 miles from Saigon, from within ‘neutral’ Cambodia. Unsupported by American bombing, funding for which was withdrawn by a Democrat-controlled US Congress, there was a collapse in Vietnamese army (ARVN) morale. As Le Duan, pointed out, ‘never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage so great as we have now.’

The attack on Phuoc Long Province was followed by an advance across the central highlands to cut off the ARVN forces defending the 60-mile border with North Vietnam along the 17th Parallel. With Saigon pressed from the West, and South Vietnam cut in half, defeat was now inevitable; on 30 April 1975, North Vietnamese tanks entered Hanoi and ‘liberated’ Saigon.

Subsequently it became a frequent charge that Nixon and Kissinger had orchestrated a US withdrawal to allow a decent interval before South Vietnam’s inevitable collapse. Not true. From mid-1973, Nixon and his secretary of state Kissinger were denuded of the executive power to conduct a defence of South Vietnam. Congress blocked the bombing of the Ho Chi Minh trail. Without access to American Air Force support, South Vietnam was laid bare to Giap’s flanking operations along its extensive Laotian and Cambodian borders.

In addition, the Democrat-controlled congress also chose in successive years to cut military aid to their South Vietnamese allies; it was another shattering blow to their morale. Nixon’s policy of ‘Vietnamisation’ of South Vietnam’s defence and post-Paris Accord survival was predicated upon the continued provision of air support and military aid; without it the South Vietnamese government could only wait for the north to gather its forces. Compounding the sequestration of American aerial and financial support was South Vietnam’s economic collapse after the withdrawal of America’s 250,000 troops and support staff.

By 1968, normal economic activity in Vietnam had all but ceased. The economy had become reliant on providing support services to the fantastically well-provisioned American army. US soldiers could be lifted out of a firefight with the Viet Cong and minutes later be eating steak and fries with ice-cold beer and ice-cream in air-conditioned bases. The infrastructure to support the US army was immense; the Vietnamese economy had in effect become a slavish support structure for the American military.

It did not help that America became distracted by Watergate and Nixon’s impeachment

In recent years, the left-dominated narrative in American universities has focussed blame on Nixon and Kissinger for the Vietnam war in its entirety and the fall of Saigon. Hence Stephen Young’s 1923 book Kissinger’s Betrayal: How America lost the Vietnam War. However, in apportioning blame for the fall of Saigon, the larger part must fall on a US political system that effectively washed its hands of support for an independent South Vietnam after the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. It did not help that America became distracted by Watergate and the impeachment of President Nixon.

However, historians should look much further back than this. From the beginning, America never fought to defeat North Vietnam or fight for the defence of all of Indochina. President Dwight Eisenhower, the former Supreme Commander in Europe in the second world war, in handing over to President Kennedy, had warned that losing Laos would lose all of Indochina, South Vietnam included.

Defending South Vietnam’s 60-mile border with the North would have been relatively easy. But defending a 1170-mile border with Laos and Cambodia was a near impossible task. Here, the fact that President Kennedy was suckered into an agreement on Laotian neutrality with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev at the Vienna Summit in June 1961 proved fatal for the future conduct of the war in Vietnam.

Then, after Kennedy’s assassination, his successor Lyndon Johnson focussed his political energy on his ‘Great Society’ welfare reforms rather than on attempting to defeat North Vietnam. Johnson fought the war as no more than a holding operation.

By the time Nixon came to power in 1969, after seven years of war, America had lost the will to fight. Ultimately the elegant solution devised by Nixon and Kissinger to force a peace treaty with North Vietnam and then ‘Vietnamize’ the defence of South Vietnam was scuppered by a Democrat Congress’s unwillingness to pay for it. It was a failure that has subsequently been repeated by the United States in other theatres. Indeed, learning from history has not been a characteristic of post-war American foreign policy.

As a last word, it should be noted that the Vietnam War was not completely without value to the West. Lee Kuan Yew, the founding prime minister of Singapore, and one of the great statesmen of the 20th century, observed that the war, badly fought as it was, played a critical role in providing Southeast Asia with time to strengthen itself against the threat of communism.

Comments