The hacking of the Electoral Commission’s databases highlights the way that in the interconnected modern world, ‘warfare’ can be as much about undermining faith in a country’s institutions and disrupting its political processes as anything else.

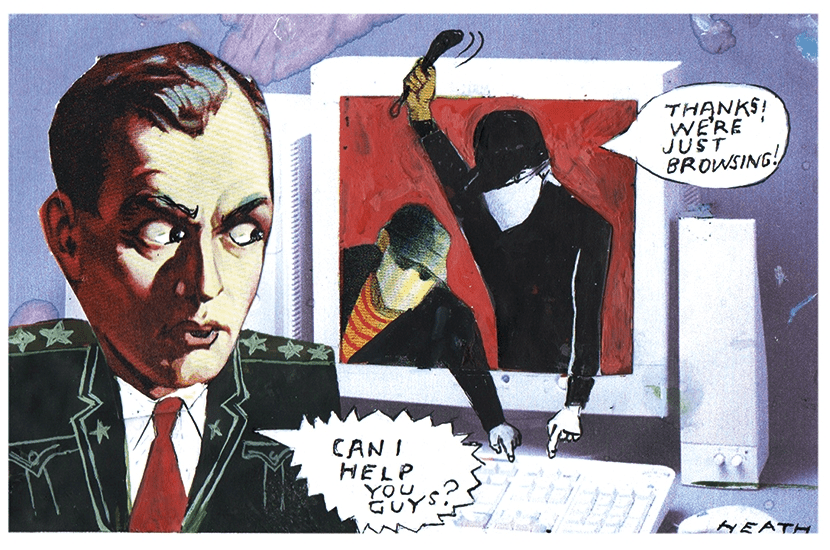

The Electoral Commission has admitted that ‘hostile actors’ penetrated their systems in August 2021, in a ‘complex cyberattack’ that was only detected in October 2022. In those 14 months, the hackers accessed the details (most, admittedly, openly available) of up to 40 million voters, as well as the commission’s email system.

One former Russian spook from the SVR once admitted to me that ‘MI6, CIA and the rest are the opposition: it’s the FSB who are the enemy’

Was it the Russians? Apparently, the security services have found evidence connecting this to Moscow, but in the absence of any more concrete information it is hard to know how to assess this. The trouble is that these days, the Russians are once again the all-purpose bugbear and we have already heard a queue of former spooks lining up to point the finger.

The sophistication of the attack and yet the lack of any evidence that the breach was monetised does suggest that these were not simply criminals looking for a score but state actors. That need not mean the Russians, and Sir Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6, said he ‘would put the Chinese second because of the value that they place on the long-term collection of data related to their strategic interests.’ (Iran also has targeted elections in the past.)

Nonetheless, there are good reasons to suspect that the Russians are indeed behind it. They have form in running sophisticated and long-term hacking operations against western administrative and political infrastructures, and also in trying to influence elections and undermine faith in democratic institutions. It is still open to question whether they were specifically trying to get Donald Trump elected in 2016 rather than undermine what they saw as an inevitable Hillary Clinton presidency, let alone how much effect they really had. However, it is incontrovertible that they did hack, leak and spread disinformation, doing their bit to help stir up the toxic partisan politics that still tears at the fabric of the US political system today.

Likewise, they stand accused of leaking documents on trade negotiations with the USA as part of a campaign to meddle in the 2019 general election, and both Paris and Berlin have accused Moscow of seeking to interfere in their respective elections in 2017. No wonder Sir David Omand, former head of GCHQ, told Radio 4 that they were ‘first on my list of suspects,’ while erstwhile head of MI6 Sir Richard Dearlove agreed that ‘Russia would be at the top of the suspects list by a mile.’

Why bother, though? In part it may simply be opportunism. The Russian intelligence community is as horizontally competitive as any other element of Putin’s state. The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), the Federal Security Service (FSB) and military intelligence (technically GU, although still widely known by its old acronym, the GRU) all have their own independent hacking teams. They operate in a cannibalistically competitive environment in which they are at least as concerned with one-upping their rivals in Putin’s eyes as advancing the cause of the Motherland.

One former Russian spook from the SVR once admitted to me that ‘MI6, CIA and the rest are the opposition: it’s the FSB who are the enemy. If I ever came up with anything that made them look bad, that was what would get me a medal.’ Thus, if one team happened upon a vulnerability in the Electoral Commission’s defences, it may have exploited it simply to meet its targets, and provide ammunition for its agency in its perpetual struggles with its rivals: see, we have penetrated the heart of the British political system (never mind if anything much could be done with that access).

More seriously, though, the aim could have been to undermine the credibility of the electoral process. There are suggestions that ransomware was inserted into the system. This is typically used to force companies or individuals to pay to regain access to their data, which could also have been used disruptively. Given Britain’s continued use of paper ballots, the scope for serious electoral fraud is limited. However, were the Electoral Commission to be locked out of its own voter lists before a ballot, this could cause uproar, recriminations and suspicion out of proportion with any real malpractice.

With modern western democracy in some kind of a crisis, the scope for hostile actors – whoever they may be – to disrupt and subvert free and fair elections are all the greater. The Electoral Commission has said that the ten-month delay in announcing the breach was to allow time security to be improved. Let’s hope so.

Comments