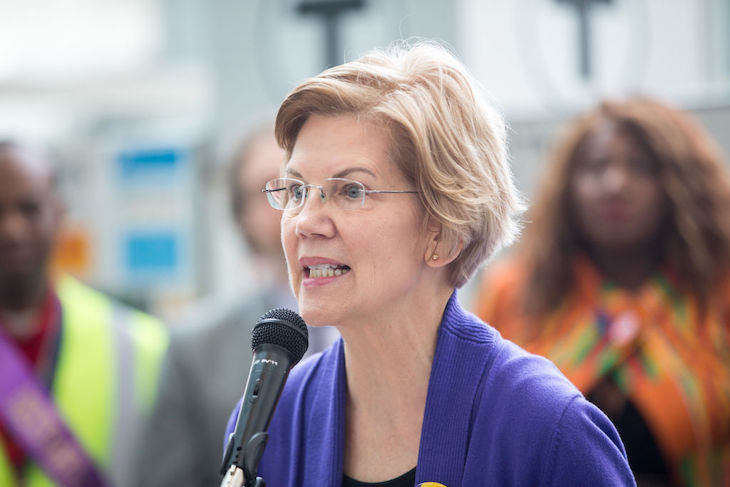

Wealth taxes are back in fashion. In the United States, Senator Elizabeth Warren is proposing an ‘ultra-millionaire tax’. In the UK, there are calls for greater taxation of property from a coalition stretching from Lord Willetts, a former Conservative minister, to Owen Jones and other Corbynista activists. I say ‘back’ in fashion, because these taxes appear to be subject to a cycle of sorts – endlessly proposed, debated, then… quietly set aside.

Most of the recent UK examples have focused on property. The Tories’ ‘dementia tax’ – a phrase coined by Policy Exchange’s Will Heaven in The Spectator – is remembered all too well from the ill-fated 2017 election. Before that there was Ed Miliband’s ‘mansion tax’, proposed in 2013, which was to be targeted at homes over £2m in value. There was Nick Clegg’s one-off ‘emergency’ wealth tax proposed in August 2012, and a ‘tycoon tax’ proposed in March earlier that year with little detail – other than that it would be aimed at millionaires. Those with longer memories will recall Denis Healey’s promise to ‘tax the rich until the pips squeak’. That resulted in a capital transfer tax but his proposed wealth tax never materialised.

All had one thing in common: they never got anywhere. But they reveal a couple of things. First, how wealth continues to be an attractive political target, because it is distributed much more unequally than income and is complimented by trends such as soaring CEO-to-worker wealth ratios. Second, when push comes to shove, most people just won’t put up with these taxes. They prefer the idea of passing the wealth they have to their children directly, instead of hoping that more government spending enabled by redistribution will have the same or similar effect. Polling shows that the inheritance tax remains Britain’s most unpopular tax, despite affecting just 29,000 estates in 2016-17. It is likely to stay that way as asset price inflation pushes more and more households into its grasp.

In policy terms, the conclusion reached by Sen Elizabeth Warren and others is to ensure new wealth taxes only hit the very richest. Warren has floated what she calls, on social media, the #UltraMillionaireTax – a 2 per cent levy on every dollar owned beyond the first $50 million in assets, rising to 3 per cent on every dollar above $1bn. It would affect the 75,000 richest households in the US. Her economic advisers are claiming, rather optimistically, that it will raise $2.75 trillion over 10 years – roughly the UK’s total GDP for 2017. Interestingly, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party currently has no such plans for a wealth tax aside from reforms to property taxation, but who knows what his conversation earlier this week with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the star of the new left, might lead to.

Do these taxes ever work? Let’s look at the evidence from around the world. In 1965, nine OECD countries, including Germany, Austria and the Netherlands collected what are called net wealth taxes on individuals, a specific form of wealth taxation where all of an individual’s wealth – property, shares, cash, valuables, everything – minus liabilities, is taxed. By 1996, that number had risen to 14, but it had dropped to just six by 2019 – Spain, Switzerland, Norway, Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands.

Why the sudden drop off? Simple enough: all the countries found that wealth taxes weren’t raising enough to justify the economic, administrative and political costs. According to a 2018 OECD study, net wealth tax revenue as a percentage of GDP in 2017 ranged from 0.2 per cent in Spain to just over 1 per cent in Switzerland. More interestingly, the amount brought in from these taxes remained flat or even decreased in the long run, despite significant increases in wealth accumulation, which undermines the idea that that they can be – in the long-run – an effective solution to excessive wealth. Looking again at Switzerland, according to a study by the economist Jonathan Gruber, for every 0.1 per cent tax on wealth, the number of people paying the wealth tax dropped by 3.5 per cent. ‘When you tax people’s wealth, they manage to somehow reduce their taxable wealth,’ says Gruber.

The truth is that wealth taxes exhibit an unavoidable and awkward feature: in order to raise significant amounts of revenue, they need to apply not just to the super-rich. And they need to have few exemptions, as this minimises the impact of individuals taking steps to avoid them and prevents distortions (towards any exempted categories). The Swiss tax generally meets these criteria and therefore raises the most in revenue, but the result is a tax that hits the middle class. On the other hand, a broad base imposes a burden on asset-rich but cash-poor individuals, which is a particular problem in countries where property prices rise rapidly relative to incomes, such as the UK. Few exemptions, meanwhile, could lead to wealth taxes on business assets, which could have a negative effect on business investment. The bottom line: is all of this worth it when the most successful international example raises just 1 per cent of GDP?

What about the UK? Since we have fewer billionaires, it’s the stock of residential property wealth which is being eyed up by the Left. Taxes on immovable property are more difficult to avoid than net wealth taxes. But they do suffer from many of the same problems, such as difficulties associated with valuation, the problems associated with asset-rich, cash-poor individuals, and the cultural factor associated with property in the UK. As Michael Gove once put it, ‘an Englishman’s word is his bond, his home is his castle and Jack’s as good as his master.’ Owning your own home is seen as a reward for years of graft, and one only has to look at the ‘dementia tax’ to judge the public’s readiness for sharing this asset with others, especially when – relative to other rich countries – we already share quite a lot via other property taxes.

Ultimately, there is simply no escaping the fact that wealth is far more difficult to tax than income. Neither the mountains of wealth held by the world’s richest billionaires, nor Britain’s store of pricey property, will ever be a surer way to prosperity than genuine wealth creation and economic growth. Those are the things policymakers should be looking for – not new ways of taxing us.

Jan Zeber is a Research Fellow at Policy Exchange

Comments