Cairo

Cairo

The Facebook and Twitter revolutionaries are taking a beating at the hands of the Brothers. The results of Saturday’s referendum are now out and they point to a simple truth: the internet was fine as a tool for gathering a few hundred thousand youths in Tahrir Square; but it is largely irrelevant as a means of winning elections across large swathes of Egypt, where three-quarters of the 83 million population have no internet connection at all.

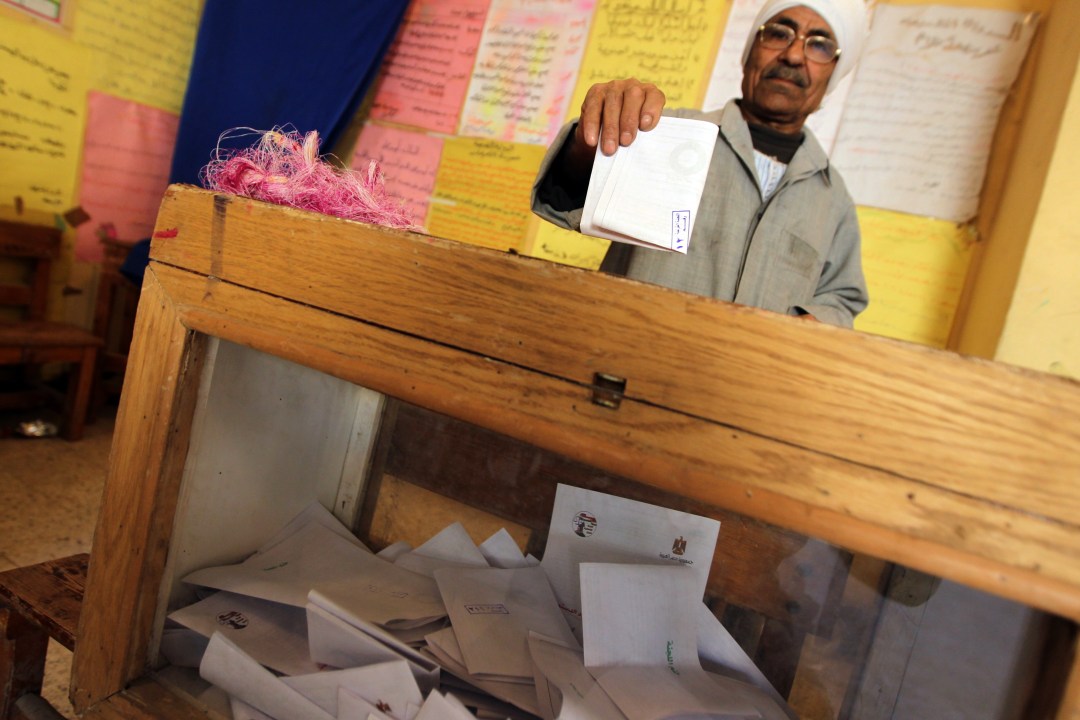

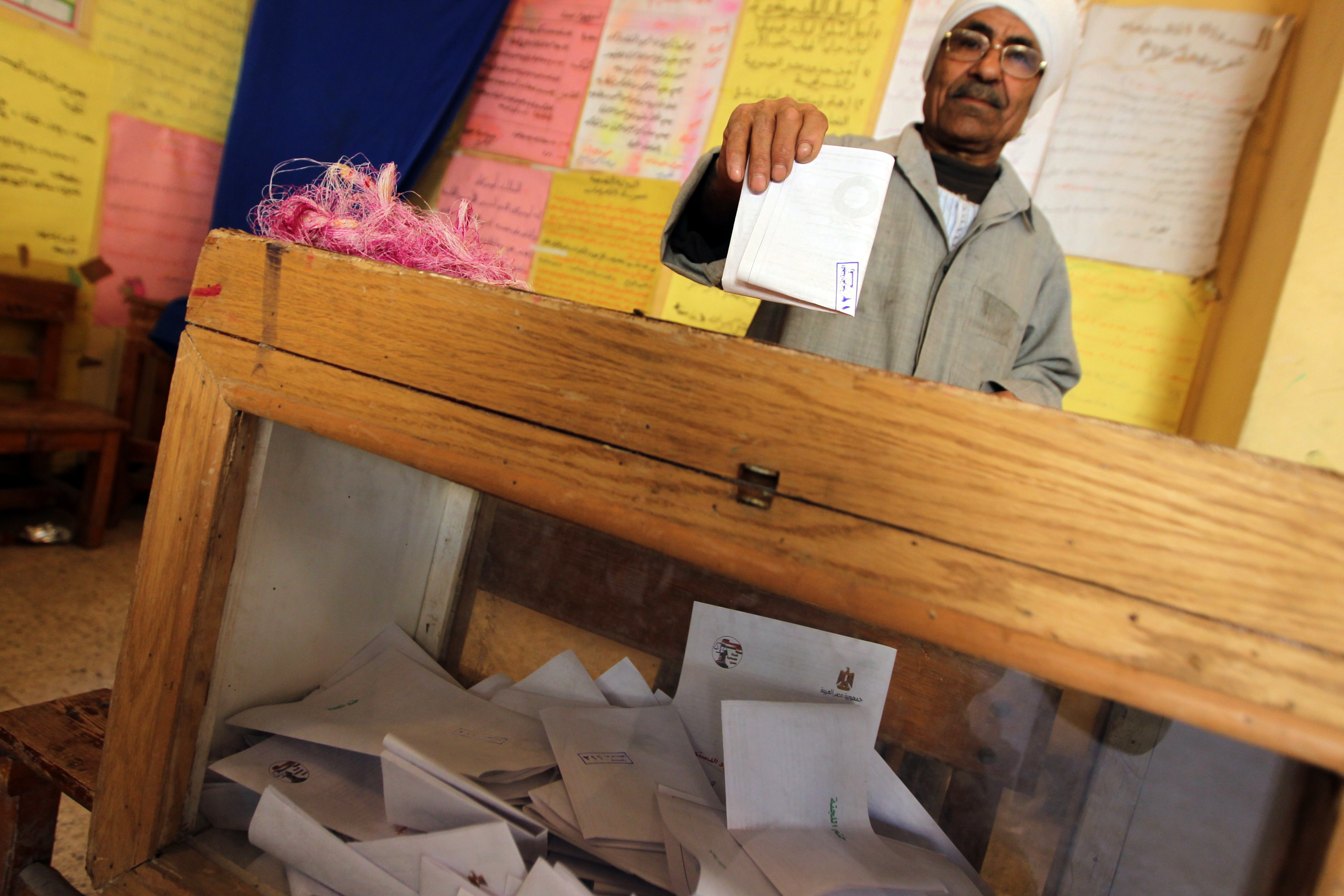

On a massive turnout, and in the fairest vote in the country’s modern history, 77 per cent of Egyptians sided with the Muslim Brotherhood in saying “Yes” to a quick and dirty patch-up of the existing Constitution. This means early elections and a likely clean sweep for established political groups, namely the Brothers and the remnants of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party (NDP), at a time when the twitterati have yet to organise themselves into coherent political parties.

A vote that the Facebookers ill-advisedly decided to transform into a referendum on the Muslim Brotherhood has given the once banned movement a popular legitimacy that is now hard to deny. The Brothers are not just reaping the rewards of their years as the only visible opposition to the Mubarak regime. They also ran an aggressive and disciplined campaign, declaring that it was a religious duty for all Muslims to “Vote Yes” to the proposed constitutional amendments.

In poverty-stricken and rural areas, where the Brothers have for decades provided religious education and undertaken charitable activities, the message found a particularly receptive audience. Ranged against the Muslim Brotherhood in calling on the public to reject the changes were the new secular liberal parties now springing up in Cairo backed by the Tahrir Square revolutionaries. Their call for a “No” fell on deaf ears.

Wracked by soaring unemployment and food prices, the average Egyptian wants stability, not endless protracted constitutional wrangling designed to buy time for emerging new political parties to organise themselves sufficiently to take on the Brothers and the NDP. Unlike former Tunisian President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali’s political machine, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), Mubarak’s NDP has yet to be dissolved and remains a force in semi-feudal rural areas.

Egypt is now hurtling towards parliamentary elections, to be held possibly as soon as June, and then presidential elections, due by the end of September. These will see the Muslim Brothers, until recently a banned organisation, almost certain to emerge as the single largest party in the next parliament and the most powerful political bloc in the country. The liberal parties now taking shape are chronically fragmented, badly organised, overwhelmingly urban and lacking in leadership.

The result is that liberal democracy will not replace despotism as easily as Washington and London might hope. Analysts expect the Brotherhood, whose slogan is “Islam is the solution” and whose goal is to make the Koran the organising principle for the life of the Muslim family, individual, community and state, to pick up 40 per cent of seats. Such a share would force British ministers to reflect hard on whether they can continue to refuse to engage with the Brotherhood’s leadership.

At various times in its history, the group has used violence and, under Mubarak, was outlawed for trying to overthrow his relatively secular government. But since the 1970s, it has abandoned violence and sought to participate in politics. International perceptions of the movement will hinge on evaluations of the extent to which it attempts to use its likely parliamentary strength to force the introduction of sharia law and fundamental changes to the treaty based on the 1978 Camp David accords with Israel.

At the headquarters of the Muslim Brotherhood, a dusty building in the centre of Cairo, Essam El Erian, a senior spokesman, unsuccessfully attempts to be reassuring. “Egypt will only introduce sharia law if it is the will of the people in parliament,” he says. “Egypt is a civil state in which people are the source of authority and they will only want sharia law in accordance with democratic means. Let’s leave further questions on this for later.”

He is equally evasive on the Brothers’ likely stance vis-a-vis Camp David. “Our position has not changed, but it is for the new parliament to decide. We are in a new period and everything must be reviewed. Who created Israel and supported dictatorships to look after Israel? The west. Now the dictatorships are gone, it is the moment of truth. What are you going to do with Israel? How can Israel live in a democratic region, that is the question?”

Yet such rhetoric disguises growing divisions within the Muslim Brotherhood and the emergence of moderate Islamist centres such as the new Al-Wassat (Centre) Party. These reformist and pragmatic groups are challenging the hegemony of the conservative old guard. Sondos Asem, 24, a young headscarf-clad woman, is typical of the reformers seeking to hold internal elections that will bring more women and young people into the membership and governing structures of the Brotherhood.

“People need to understand that we’re not the extremists Mubarak painted us as,” she says, noting that the movement is not fielding a candidate for the presidential elections. “The Muslim Brotherhood knows that people need time to be exposed to us as a political group. Even now, many intellectuals are scared of us, see us as an extremist group that just wants to seize power and turn us into a theocracy. That might be true of the Salafist movements, but not the Muslim Brotherhood. Mubarak really used us as a bogeyman.”

Yet the idea that the Muslim Brotherhood might transform itself into a more open, democratic and tolerant organisation does not persuade Ahmed Maher, an internet activist wearing the hoodie, jeans and trainers uniform of the Tahrir Square heroes. “I’m really anxious genuine democracy will be de-railed,” he says. “The forces that want to de-rail it – the Muslim Brotherhood and the hangovers from the old regime in the NDP – are more organized than those promoting it.”

Wael Ghonim, Google’s head of marketing and an emblematic figure for the Facebookers, also looks deflated on the day of the referendum, after riffing to a half-empty auditorium in the trendy Zamelek quarter of Cairo about the need to get more people onto the internet. But he also says it is time to stop isolating the Brothers. “They are not terrorists. They are part of us. We must give them a chance. They’ve promised not to go for a majority and I believe they’ll show restraint.”

The Brothers know any new government will rapidly become unpopular. Tourism chiefs have written off the season. Business investment has dried up, amid a purge of Gamal Mubarak’s cronies that has left scores under investigation and the likelihood of populist economic policies in the months ahead. The stock exchange has been closed for weeks. A million Egyptians have flooded back across the porous Libyan border, pushing up unemployment and depriving the economy of remittances.

The result is that growth is slowing to a halt. The budget is in a mess. Capital is fleeing the region. Unsurprisingly, a sovereign financial crisis looms. Nearly half of Egypt’s reserves have left the country in the last two months. The IMF arrives this week and will have to look hard at ways Egypt can put its public finances back on a sustainable path without imposing hair-shirt measures that could trigger a popular backlash and derail the political transition to democracy.

The west will have its part to play in ensuring that does not happen, and not just in fast-tracking the return of frozen regime assets. If it is serious about assisting the political transition, and about putting some substance into the ‘progressive narrative’ we seek for ourselves in this new era in the region’s history, it will need to help Egypt economically. This means taking a hard look at the debt that Egypt is lumbered with thanks to the former dictatorship – if not in terms of forgiveness, then perhaps in the form of sovereign guarantees of Egyptian borrowings to lower Cairo’s financing costs.

It also means helping Egypt to find a more sustainable pricing mechanism for its industrial exports, 30 per cent of which go to the EU’s 27 states. Re-writing many of the contracts the Mubarak regime signed with the Club Med countries closest to the former president would be a start. Gas supply deals with Italian, Spanish and French companies may be losing Egypt $7bn a year alone, but they are not the only ones ripe for renegotiation.

The big unknown facing Egypt now is what type of democracy the army will tolerate. The military has thus far played a positive role in the political transition, in that it has not actively opposed change, but its instincts are hardly revolutionary. Stability, rather, seems to be its overriding objective. A system dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood and the discredited crony capitalist remnants of the NDP may provide a form of democracy-lite that the generals can command and control.

By pushing for quick elections, in a manner that will undoubtedly favour the most reactionary forces in Egyptian society, the Muslim Brotherhood and the NDP, it is feeding conspiracy theories across Cairo. The military was always an unlikely bedfellow with the twitterati and the activists organising flashmob demonstrations over Facebook. A more circumscribed form of democracy may suit it by limiting scrutiny of the army’s budget and of its role as an important player in the Egyptian economy – the much-mooted Turkish model.

One thing is clear, however: the transition from despotism to liberal democracy in Egypt is as fraught with risk as anywhere in the region. The west must resist the temptation to try to pick winners among the various political actors, but it can play a valuable role in alleviating some of the mounting economic pressures that could de-rail the emergence of a more democratic system of government. If it is serious about creating a progressive narrative for its policies in the Middle East, work must start now on the Egyptian economy, before it is too late.

Jo Johnson MP is the Conservative MP for Orpington

A (very) condensed version of this post is the second leading article in the current issue of the magazine.

Comments