Lolita, the Lady Chatterley trial, the pill, Christine Keeler, ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’, love-ins, Oh! Calcutta!, the Oz trial — sex, even more than usual, was on people’s minds in the 1960s, that semi-mythical decade which, to stretch a point, lasted from the late 1950s to the early 1970s.

That, anyway, is the plausible contention of Peter Doggett, whose Growing Up is a refreshingly undogmatic, well-researched and highly readable survey of some of the emblematic episodes and controversies surrounding the subject during these years. More detailed sociology would have been helpful — how, if at all, did everyday/everynight sexual practices and attitudes change in Barnsley, in Dunfermline, in Ashby-de-la-Zouch? — but the considerable compensation is Doggett’s ability to stand back and enable the potentially overheated reader to see a bigger picture. Specifically, he argues that the era’s famed sexual revolution (largely in the UK, though he also deals with the US) comprised three main aspects: the counter-culture; liberalisation; and commercial exploitation.

‘We tried to show we were very beautiful, but people said we were very ugly. We were very surprised’

How long ago that counter-culture now feels: the Festival of Underground Movies in autumn 1966; Jim Dine’s candid depictions of sexual organs provoking a raid by the Met on Robert (‘Groovy Bob’) Fraser’s gallery; the underground mags International Times (IT) and Oz (an abundance of gratuitous female nudes); above all, John and Yoko, those two virgins looking naked and unflinching at the camera. ‘We tried to show we were very beautiful,’ said Yoko five years later. ‘But the people said we were very ugly. We were very surprised.’

The cardinal non-meeting of minds was between Mary Whitehouse, untiring advocate of Christian teaching on pre-marital sex, and Oz magazine’s Richard Neville, celebrant in his Playpower manifesto of meeting a ‘moderately attractive, intelligent, cherubic 14-year-old girl’ on her way from school, sharing a couple of joints, molesting her and leaving her to head home and finish her homework. Doggett reflects:

Even though the hedonistic impulses of one’s imagination might prefer Neville’s Edenic playground to the staid, censorious landscape of Whitehouse, one can’t help wondering whether the veteran schoolteacher, who never forgot her anxious sex-ed pupils, might have been a more reliable moral guide for this particular teenager than the prophet of sexual freedom.

I agree, though have often wished that in her self-appointed mission to ‘clean up’ television and much else, Whitehouse had concentrated less on the sex, more on the violence.

The campaign to legalise homosexual relations between consenting adults, and the immediate limits of what it finally achieved in 1967 (in terms, for example, of police attitudes), is well-worn territory, fairly enough summarised by Doggett. Instead, he directs his fire largely elsewhere: on the media for their overwhelmingly negative image of lesbians (‘I, like most other heterosexual women, prefer not to think about lesbianism,’ Marjorie Proops told her Daily Mirror readers in 1969, as she warned against it becoming ‘a vicious cult’); on doctors, therapists and psychologists for continuing to search for an elusive magic cure for homosexuality, including through electro-shock and aversion therapy; and on society generally for its unwillingness to treat transgender issues either seriously or sympathetically (though not mentioning the subject of Zoë Playdon’s poignant new book, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes, about someone who, many years after transitioning, was compelledin court in 1967 to defend his gender).

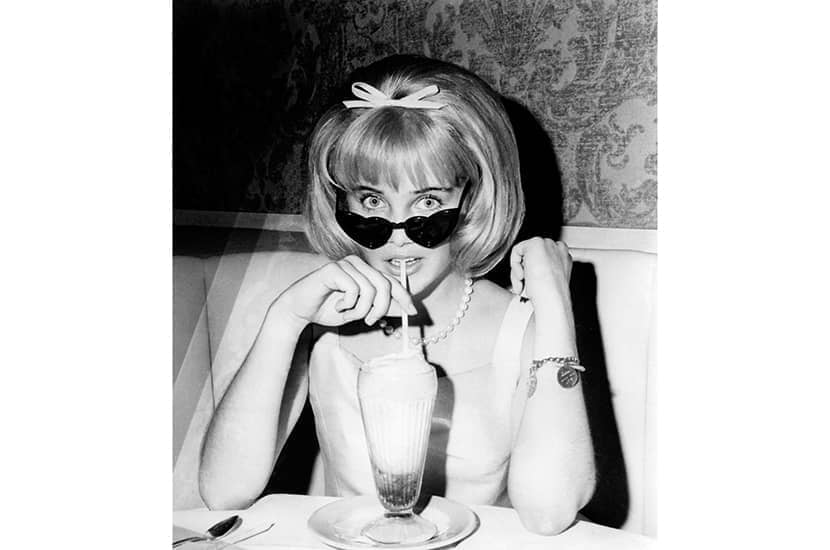

Doggett is also rightly critical — though often in a more ironic, even humorous vein — of the relentless commercialisation of sex, involving as it did an almost systemic objectification of women in general and young girls in particular. Soft-porn men’s magazines (including Penthouse, with its penchant for extolling the pleasures of caning teenage girls), misogynist mainstream films, such as the rampantly male Alfie, and a dark strain of pop-cum-rock music (culminating in the topless 11-year-old girl clutching a phallic spaceship on the cover of Blind Faith’s 1969 album) were all increasingly just part of the daily furniture. So, too, fashion photography. ‘There they stand, legs apart, mons veneri thrust forward, their mouths open,’ noted one observer in 1967 after a day spent inspecting posters on the London Underground of swimsuited girls simulating for the male gaze ‘the last stage of orgasm’.

Growing Up is Doggett’s deliberately loaded title. The same title as the explicit and instantly notorious 1971 sex-education film (‘This is quite simply public sex,’ declared Whitehouse), it also implicitly poses the question of whether the British in the course of the 1960s really did acquire a new maturity — more tolerance, more emotional intelligence, less infinite repression of desire — in matters of sex. Given we still awaited Confessions of a Window Cleaner let alone No Sex Please, We’re British; given the heyday of Page Three was yet to come; given it would be another quarter of a century before we began to have public acceptance of openly gay MPs, the answer can at best be only a heavily qualified yes.

Comments