Last week, when Ed Vaizey declared that 6 Music should be exempt from these pending BBC cuts you’ll have heard about, he should not have sounded so odd.

Last week, when Ed Vaizey declared that 6 Music should be exempt from these pending BBC cuts you’ll have heard about, he should not have sounded so odd. Insincere, maybe. Opportunistic, certainly. But not odd.

I’ve only met the man once, true, and then for about nine seconds. Still, from the times I’ve seen him on TV, and from the amusingly rude emails he sent me once after I misspelled his name, I’ve always thought him the living disproof of the old myth that anybody youngish and Tory must have been strident, friendless and bald since the age of about 11. When he became a cheerleader for a trendy, off-beat music station, it should have sounded like the most natural thing in world. It should not have sounded how it did, which was like the Duke of Edinburgh asking to borrow your crack-pipe.

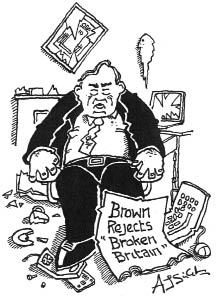

Eight weeks before an election, the battle of 6 Music ought to be where it all comes together for the Conservatives. Forget reforming the BBC for a moment. Forget the ideological debates about the reach of the state, and the limits of the private sector. Think demographics. When the polls see the Tories slip by eight points, who do you reckon those eight points are? They’re not suddenly Ukip voters, are they? They haven’t gone to the BNP. They’re not Eurosceptic climate-sceptics, yearning for a repeal of the fox-hunting ban and a bold and forthright position on flat taxes. Honestly, what madness is this? No, that eight points is the floaters. The ones in the middle. They don’t all listen to 6 Music, sure, but the ones who do are fairly emblematic of the whole.

The average 6 Music listener is 36. The average. This isn’t yoof. It isn’t hoodies and thugettes with sideways ponytails knifing each other on buses and saying ‘innit’. This is young, professional, aspirational Britain, heading towards middle age, but with all the cultural anchors of teenagers. A couple of kids of their own, a decent job, but they never quite grew out of the Stone Roses. This is middle-class Britain. Their equivalents went nuts for Blair in the 1990s, but this lot aren’t going nuts for Cameron. Not even nearly. And that’s where it’s all going wrong.

And Cameron, after all, is one of them. At Eton, he loved the Jam. At Oxford, the Smiths. These days, the Killers. He’s even sampled the latter in the music he plays when he comes on stage at conference. As surely as the sky is blue, there must be a highly enviable Bose digital radio sitting in the Cameron’s highly enviable kitchen, and that radio, well, it won’t be tuned to TalkSport, will it? This is an aspect of Cameron’s personality that has always sat uncomfortably with all else that he projects — what is it like to listen to ‘The Eton Rifles’ when you are an Eton Rifle? How can you be in the Bullingdon Club and also bop along to ‘The Queen Is Dead’? — and he continues to miss a trick in failing to explain how it connects.

Maybe it doesn’t. But hell, he could at least pretend. This stuff is easy. Years ago, when Paul Weller sneered at the whole Eton Rifle thing, Cameron was vague and defensive. No, Dave! Wrong! You loved it because simply being on the right side of inequality doesn’t blind you to it, right? And it made you determined to raise the lot of the beleaguered poor, right? So that everybody could enjoy ‘The Eton Rifles’ like an Eton Rifle can. Right? I mean, Christ, man, pull your thumb out. Anybody can do this. It’s only pop. But it is also the narrative by which vast numbers of people live their lives. There’s simply no excuse for weakly surrendering every aspect of it to the other side.

Show me a pop star, after all, and I’ll show you a Tory. Yes, all of them. They may not talk the talk, but they surely walk the walk. Even Billy Bragg, pop’s greatest socialist, has a vision of England that he shares with John Major, and which would bring Ed Balls out in hives. The socialism of pop has always been a front. Punk was nothing but a symptom of man’s eternal yearning for smaller government. New Romantics were basically Margaret Thatcher; monetarists with backcombing. Britpop was adopted by Blair, but it was a product of Major. Long before Cameron and Zac Goldsmith were wafting around being wealthy environmentalists with a teenager’s social conscience, Bob Geldof and Bono were doing the same.

Pop is about freedom and about individualism. Like football, it is all about the humble man’s dream to make a shedload of cash and not have to work down a mine. This, Dave, is your stuff. These are your people. They want to be free to do what they want to do, without getting hassled by the man. And they wanna have a party, even if they do have to be home at 11 to pay the babysitter. And you don’t speak to them at all. It’s a problem.

I’m not sure I want President Obama to stop smoking. Smokers are scary when they stop smoking. I’m a freak. And Obama is 48. If he’s likely to die of lung cancer in the next four years, stopping now isn’t likely to make a whole lot of difference. Rather, it would be an investment in his likelihood of living beyond 60, and frankly that’s not really anybody’s problem but his own. Stopping smoking now would be a selfish thing to do, and dangerously irresponsible to boot. America needs a leader who is calm and rational, and not liable to suddenly shout at people for no reason at all. Actually, maybe we could make Gordon Brown start smoking. There’s an idea.

At least when he doesn’t smoke he’s on the gum, not the patches. I couldn’t stomach the gum, but the patches made me twitchy. The lowest dose I could find was ten a day, but at the time, I was only smoking six a day. This meant that, in order to stop relying on nicotine, I was supposed to have more nicotine. It didn’t make any sense at all.

At night, I’d fall into bed, peel the patch from my arm, and dump it on the bedside table. Not infrequently, in the morning, after a night of hectic, lunatic dreams, I’d find that I had flailed somehow in my sleep, and ended up with the thing stuck to my cheek or wrist or forehead. Often it would be my wife who spotted this, not me. Imagine Obama doing the same. Imagine it happened the night before an important meeting. With, say, the Chinese. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

Hugo Rifkind is a writer for the Times.

Comments