While the government’s policy on Omicron is being driven by modelling suggesting the possibility of a huge wave of hospitalisations in January, some more real-world data has come in from South Africa.

A presentation by the South African Medical Research Council this morning has offered evidence that while Omicron does indeed appear to be more transmissible than the Delta variant, the trajectory of hospitalisations is flatter.

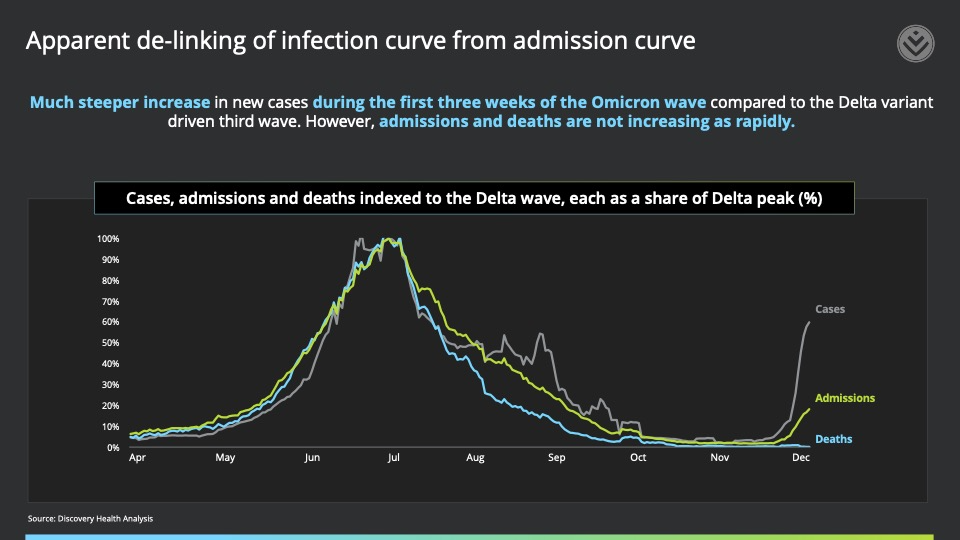

This would appear to confirm earlier data from hospitals in Gauteng province that Omicron is causing a milder disease than previous variants. Indeed, the graph of the latest outbreak shows a marked decoupling on infection figures for hospitalisation and death figures, compared with earlier waves:

The data indicates that Omicron is 29 per cent less severe than the original Wuhan strain of Covid. However, it also seems to confirm that Omicron is better able to escape the Pfizer vaccine compared with the Delta variant. Efficacy against infection fell from 80 per cent to 33 per cent, while efficacy against severe disease fell from 93 per cent to 70 per cent. That is data for vaccine efficacy – it has to be weighed against evidence that Omicron is less likely to cause severe disease.

What effect will the new South African data have on UK policy? For now, the current approach appears to have been driven by modelling from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) paper of 11 December on the Omicron variant. But this document is fast achieving the notoriety of Imperial College’s paper of 16 March 2020: the one which persuaded the government to change course from a herd immunity strategy to one of suppression, and which led to the first lockdown.

The LSHTM paper, published on Saturday, set up four scenarios regarding the spread of Omicron, the most pessimistic of which sees hospitalisations for Covid rise to a peak of 7190 a day in January – 60 per cent higher than the peak of January 2021. Within 24 hours of publication a panicked Prime Minister had announced a speeding-up of the booster programme so that every adult should have been offered a booster by the end of December, as opposed to the end of January as previously planned.

But a piece of modelling is only as good as the assumptions behind it. And as with last year’s Imperial paper, some of those assumptions are questionable.

The LSHTM paper assumes under one of its scenarios that Omicron is more transmissible and that it has the power to escape vaccines – two qualities which last Friday’s paper by the UK Health Security Agency attempted to quantify, albeit on a paucity of data.

Yet at the same time the paper ignores the possibility that omicron might be less virulent than the Delta variant. This is in spite of data from South African Medical Research Council which indicates that patients in hospital with Omicron are far less likely to require oxygen, and are likely to be able to leave hospital quicker.

Instead, the LSHTM assumes that Omicron will cause just as many hospitalisations as the Delta variant and that these will last just as long.

An analyst from JP Morgan has picked up on the LSHTM modelling and added in two assumptions of his own: firstly that the hospitalisation rate with Omicron turns out to be only 50 per cent of that of Delta and secondly that the average hospital stay falls from eight days to three days. The data from South Africa suggests that these are not unreasonable assumptions. The result? The number of people in hospital at the end of January under the LSHTM’s most pessimistic scenario falls from 106 per cent to just 33 per cent of the peak level of January 2021.

Obviously, this is all just modelling. The LSHTM paper is a preprint which has yet to be peer-reviewed. The JP Morgan assumptions might turn out to be way off beam – as indeed might those of the LSHTM. But it seems remarkable that the government has, yet again, changed course after hoovering up the worst-case scenarios presented to it by its scientific advisers.

All data on Omicron at the moment is weak and provisional, but it seems odd to accept at face value evidence that it appears to have greater transmissibility – while dismissing evidence that it seems to cause less severe illness. There seems to be a determination among government advisers in Britain – which in turn has been passed down to ministers – to accept the bad news on Omicron but to ignore the good news.

Comments