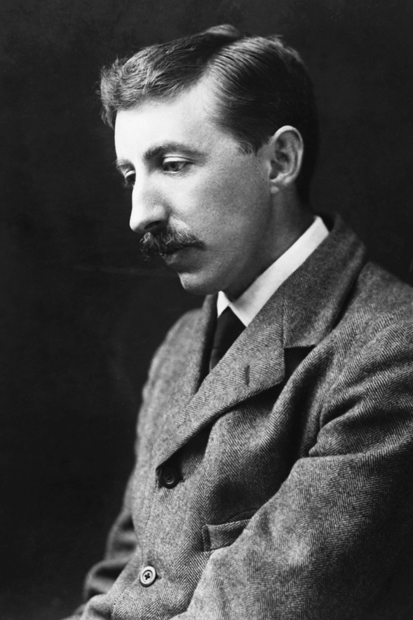

‘On the whole I think you should write biographies of those you admire and respect, and novels about human beings whom you think are sadly mistaken,’ said Penelope Fitzgerald in 1987. The South African novelist Damon Galgut has reversed this formula — with mixed results. He has written a novel about a fellow novelist, E.M. Forster, using episodes and quotations taken from a conscientious reading of biographies, diaries and letters. He salutes Forster as a writer and commends his humanity; but it is not clear whether he thinks Forster was sadly mistaken in his sexual bearings or lame in his choices.

Arctic Summer opens with Forster travelling with his fellow members of the Cambridge Apostles, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Bob Trevelyan and Gordon Luce, aboard the steamship Birmingham heading for India in 1912. They are known as the ‘salon’ by hostile passengers — officers, civil servants and merchants of the Raj, who sense their estrangement from British imperialism. One night, on deck, Forster meets an army officer called Kenneth Searight, who shows him exuberantly homoerotic poetry and tries to loosen the prim repressions of this fussy, anxious, bleating young man.

Before meeting Searight, Forster had published several successful novels with love themes — without himself having any full sexual experiences involving anyone else. True, he had shared chaste, fully-clothed embraces with another Apostle, Hugh Meredith; had been infatuated with Syed Ross Masood, scion of an Indian legal family, who reciprocated his affection but not his lust; had even been harassed by a blackmailer who overheard his unguarded talk in the Savile Club. All these people and incidents are given a thin varnish of fiction by Galgut.

So, too, are Forster’s meetings with other real-life characters. He travels to Yorkshire to meet the campaigner for sexual liberation Edward Carpenter. He goes to stay with D.H. Lawrence, who decries him as ‘cloistered, limp, ineffectual’. Sir Courtauld Thomson, the mannered bachelor who is Red Cross commissioner in the Near East, treats him sniffily. In Alexandria he shares confidences with the poet Cavafy.

Forster’s life and to some extent his novels rejected tyrannical egotism and uncurbed passions in favour of an almost masochistic docility. ‘All human interaction was power,’ he reflects in Galgut’s fiction. ‘People circled each other with poisonous intent. Every conversation jumped continually between subservience and rudeness, with no possible middle ground of genuine emotion.’

Finally, Forster begins to have furtive, hasty jiggles with other men — schoolboyish acts, which don’t satisfy Bill Clinton’s definition of sex — and notably with Mohammed, an amenable young tram driver whom he meets in Alexandria in 1917. Galgut’s account of this romance, ended by Mohammed’s early death from tuberculosis, is the most effective section in the book. Forster’s belated sexual activity enriches and frees him, Galgut implies, to accomplish the masterpiece of his career, the final novel that he wrote, A Passage to India.

Sexual discretion, divided loyalties, camouflaged affinities, cryptic meanings, suppressed identities — both sexual and inter-racial — comprise the themes of Arctic Summer. It is a decorous, ambling, old-fashioned novel, but not a surpassing success. The timidity of a man who remains a virgin until the age of 37 makes for flat reading. Even after his virginity has been shed, Forster is never adamant in Galgut’s creation, but remains a musty defeatist. One can respect the intentions of Arctic Summer; yet with its celebration of negative virtues, it is an unfulfilling book, and its final effect is inconclusive.

Galgut’s previous work has twice been shortlisted for the Man Booker prize, and his name touted as a successor to J.M. Coetzee and André Brink in South Africa’s literary pantheon. But in Arctic Summer, at least, he has rejected the luxuriance of his compatriots. Although there are scenes in the Barabar hills and the Khyber Pass, and others with maharajahs in princely enclaves, there is little sense of heat, of picturesque landscape, of exotic wildlife to quicken the imagination. This is a novel about interior states and inward cravings, not the great outdoors.

In one scene Forster hears a military band playing ‘The Roast Beef of Old England’. Galgut does not quote that patriotic ballad, but its lines condemning the emasculating effects of Englishmen eating French ragout spring to mind:

But now we are dwindled to, what shall I

name?

A sneaking poor race, half-begotten and

tame,

Who sully the honours that once shone in

fame.

For all the honour that Galgut pays him, Forster appears in this novel as sneaking and tame.

Comments