In a recent blogpost, an American economics professor called Robin Hanson asked why it is that income inequality is regarded as a terrible injustice by liberal progressives, but sex inequality — the fact that attractive people generally have more sex than unattractive people — is thought of by the same people as an unalterable fact of life that no one should complain about. ‘One might plausibly argue that those with much less access to sex suffer to a similar degree as those with low income, and might similarly hope to gain from organising around this identity,’ he wrote.

Hanson was prompted to ask this question by last week’s Toronto van attack in which Alek Minassian, a 25-year-old man who described himself as an ‘incel’ (involuntary celibate), killed ten people and injured 15, the worst mass killing in Canada since 1989. In a Facebook post that surfaced after his arrest, Minassian announced that the ‘incel rebellion has already begun’ and ‘all the Chads and Stacys’ (sexually attractive men and women) would be overthrown. In that post, Minassian praised Elliot Rodger, a 22-year-old American who killed six and injured a further 14 in 2014, before taking his own life. Rodger wrote an incel manifesto in which he raged about being sexually frustrated and vowed to take revenge on the women who wouldn’t sleep with him.

Hanson wasn’t defending these two mass murderers, but querying why incels had been dismissed in the media as ‘self-pitying’ and ‘lonely weirdos’ in the aftermath of the Toronto attack, often by the same journalists and commentators who decry other forms of inequality. Why are terrorists who murder people in the name of redistributing wealth, like Che Guevara, lionised by the left, whereas terrorists whose aim is to draw attention to sex inequality are detested? A columnist on the Scottish Daily Record said Minassian was a ‘pathetic little boy who can’t get a girlfriend’. I don’t suppose the same journalist would describe the late socialist hero Jimmy Reid as a ‘pathetic little man who couldn’t afford a nice car’.

One reason for this hostility is that many of those who identify as incels — and there are hundreds of thousands of them, mainly in America — advocate rape and sexual assault as a remedy for their misfortune. In online forums like 4Chan they describe the violence they’d like to inflict on attractive women, although they target ‘Chads’ as well as ‘Stacys’. There’s no attempt to appeal to people’s sense of justice and, as far as I’m aware, no incel has ever made an analogy between their predicament and victims of capitalist injustice. They set out to deliberately antagonise ‘normies’ — normal people with healthy sex lives — rather than elicit their compassion.

But even if there was a political wing of the incel movement, with an educated, well-mannered leader setting out their case logically and reasonably — a Michael Gove figure — you don’t get the impression it would attract much sympathy, and not just because of the excesses of its provisional wing. One explanation is that the solutions to sex inequality, such as legalising prostitution, would be politically unacceptable.

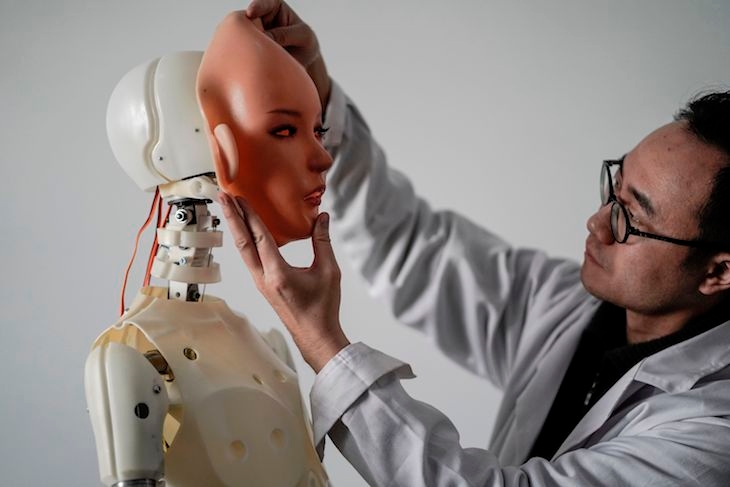

However, a more workable solution may shortly be at hand in the form of sexbots. Surely, robot girlfriends are to sex inequality what universal basic income is to income inequality? And yet, few liberal progressives are sympathetic to that idea, with plenty of ‘woke’ activists arguing that sex robots should be outlawed. ‘Sexbots reinforce an incredibly dangerous idea: that women’s bodies are only bodies, and exist only for men’s use,’ says Meghan Murphy, founder of Feminist Current.

Why is there so little compassion for the ‘have nots’ when it comes to the unequal distribution of sex? It must be because the ‘victims’ of this type of discrimination are nearly all male and, as such, classed as the oppressors not the oppressed. Indeed, several commentators on the incel movement have claimed its adherents are suffering from ‘toxic masculinity’, and suggested they attend re-education classes such as the ‘Rethink Masculinity’ course being offered by the Collective Action for Safe Spaces in Washington, DC.

As a classical liberal, I don’t have much time for incels. Their demand for sex equality is like a reductio ad absurdum of Marxist egalitarianism. But I doubt we’ve heard the last of them.

Comments