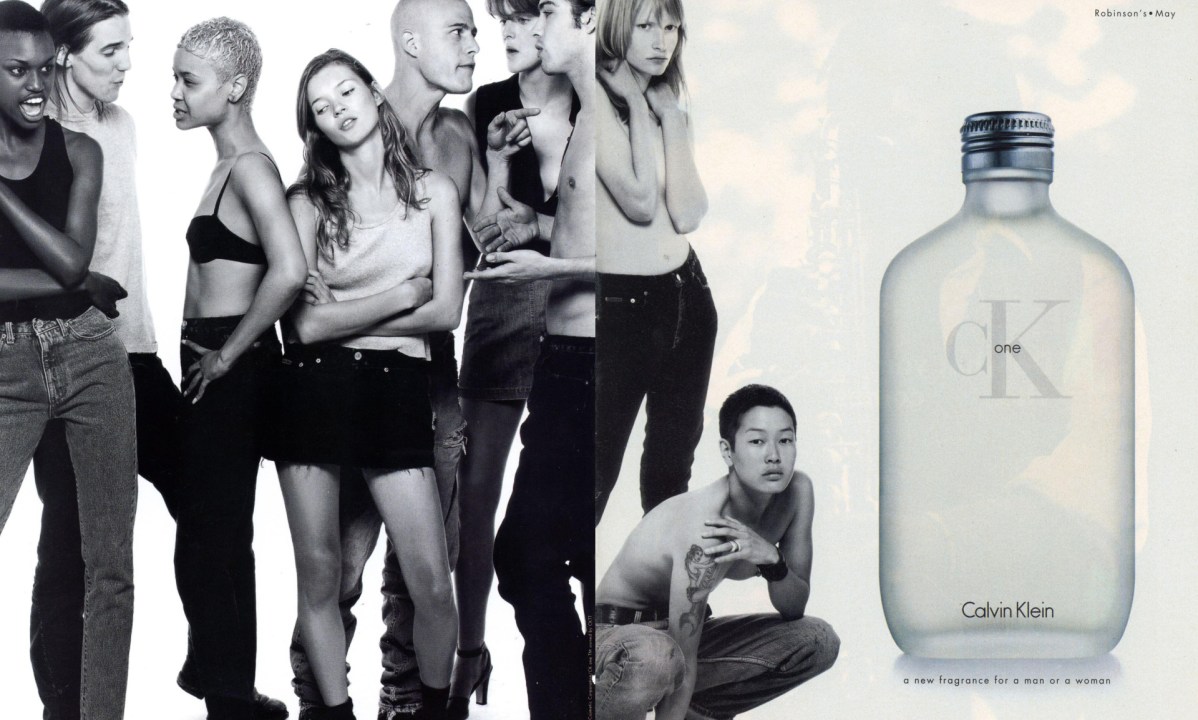

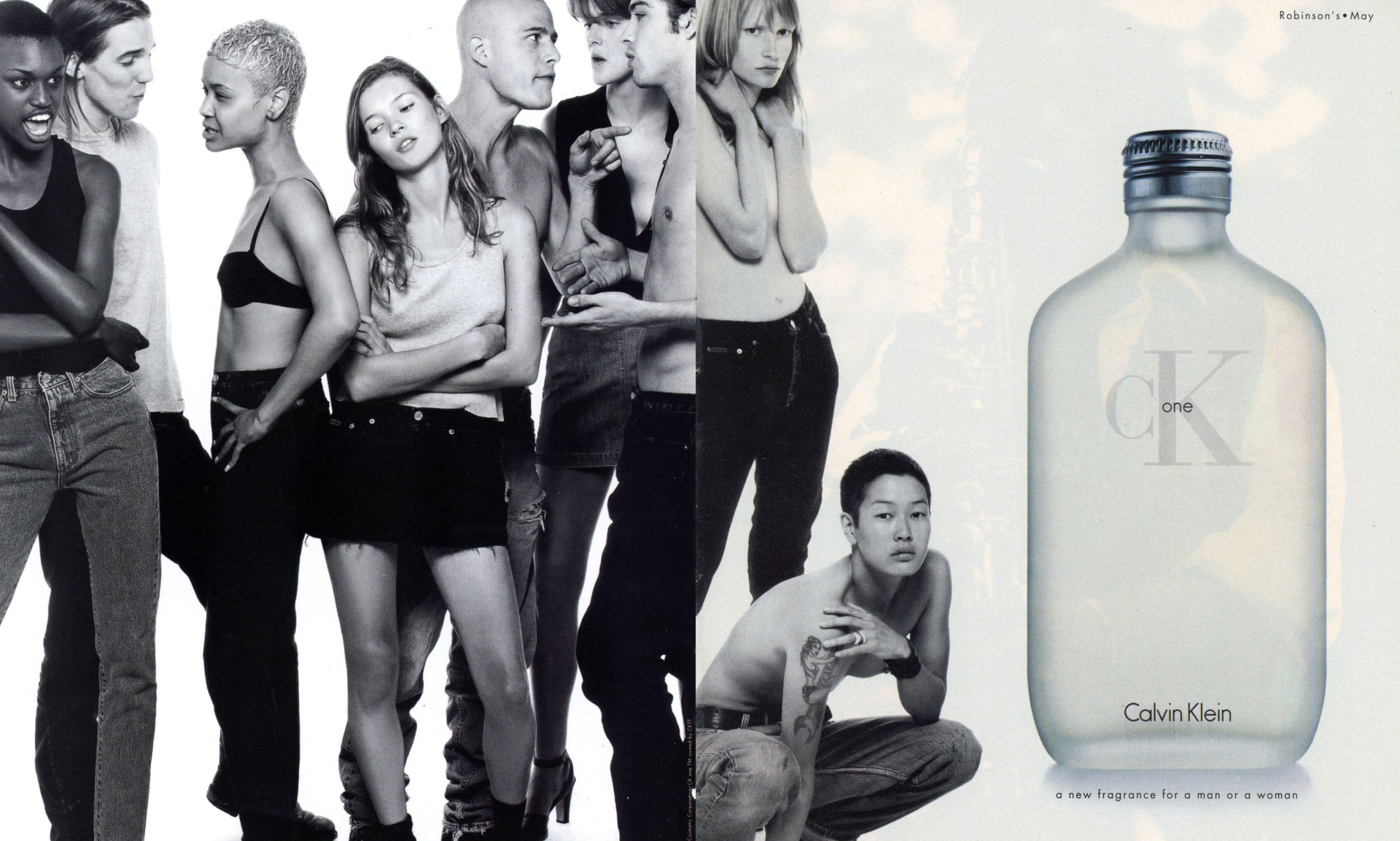

‘Nothing,’ said Vladimir Nabokov, ‘revives the past so completely as a smell that was once associated with it’. If smell is the most evocative of all the senses, it seems that Gen Z’s fabled nostalgia for the 1990s has reached new heights. It isn’t just the fashions and music they’re now spending their money on but also the decade’s fragrances.

Sales of 90s classics like ‘Joop! Homme’ and ‘CK One’ have rocketed and there has, over the last month, been a 228 per cent increase in sales of Calvin Klein’s ‘Eternity for Men’. But what if Generation Z were able simply to follow their noses and return to the 1990s themselves? Would the era smell of sandalwood and bergamot or something a great deal less beguiling?

Making a call outside your house means using a phone box that stinks of old cigarettes and last week’s urine

There’s much they’ll find a trial, not least communications. Just picture it: until the mid-1990s, anyone with a mobile phone is a yuppie or a freak. Most of us have landlines, pay vast quarterly bills, and spend our lives leaving or taking messages for others. If you have friends abroad, you can forget speaking to them: the most faltering three-minute call (complete with snap, crackle and intermittent white noise) can set you back several pounds. To ring people up, we must either memorise their numbers (a skill now lost) or carry around a small address book (the losing of which is a social catastrophe).

Making a call outside your house or workplace means using a phone box that stinks of old cigarettes and last week’s urine, with a payphone which often simply swallows your money and smartly cuts you off. Queueing for one of these cubicles in the rain while the person inside rabbits on at length is something you accept as part of modern life.

So is the awkward incoming call at home from someone you’re avoiding – only the snazziest phones show who’s contacting you, and you must simply pick up to find out. The words ‘wrong number’ in a foreign accent usually get rid of someone and are easier and less awkward than an offhand tone of voice.

But how will Gen Z entertain themselves when they land in their longed-for decade? There’s no streamable music, albums are expensive, and they’ll spend their lives making hissing home recordings on blank tapes. If they want to listen on the move, they’ll have to carry around vast piles of cassettes and back-up batteries for their Sony Walkmans. As for television, there are just four channels, with no access to their huge vaults of past programmes unless they wish to screen them. In the high street, the video rental store is king – even if the shop never, ever has the film you want. You spend a lot of time dreaming of things you’d like to see.

Then there are holidays. Gen Z will find they have to go to a travel agents in the high street to book a trip and there are few budget tickets (my first return flight to Spain, in the late nineties, cost £300, and that felt a fair price). If you want to read while you’re away, you have to take a stack of novels with you, and a heavy guidebook too for the cities you’re planning to visit (oh, and be warned, many suitcases still don’t have wheels on them).

Finding a hotel room, unless you’ve fixed it from your home country, involves making call after call to different places and, in high season, getting turned down by all of them. On the plus side, travelling will feel freer – no one can contact you on the road and if, in remoter countries, you want updates from home, you can probably read a week-old newspaper at the British Council.

There’s no such thing as ‘online information’. Facts you can access with a single click these days might, in the 1990s, take a whole afternoon in a library. Your home will be stuffed with reference books – encyclopedias, OEDs, dictionaries of biography – which along with your collection of paperbacks, VHS cassettes, LPs etc. will take up far more space.

It’s with morality that Gen Z will find themselves on another planet

Then there are those coffee table books you’ll have to own if you ever want to look at things like art without going to a gallery. Which of course, will require a coffee table too. And you must have a desk – there are no laptop computers, typewriters are too heavy to hold on your knees, and for handwriting (you’ll do a lot of it, and know all your friends’ styles by heart) you’ll need a surface to lean on. Everything takes longer, everything is lingered over a little bit more. We’re able to vanish into the books we’re reading and the films we watch.

But it’s with morality that Gen Z will find themselves on another planet. In workplaces thick with cigarette smoke and noisy with the sounds of clacking typewriters, people tease and flirt with each other (‘banter’ is about the only thing that makes life bearable) and sometimes come back drunk after lunchtime. To complain about such things will mark you out as a ninny or a prig and you’ll have no friends at all.

There’s an entirely different attitude to sex in the 1990s too. Some people are having a lot of it, others are trying to, and for a while we can talk or think of little else. At my university, a visiting elderly novelist confesses, in a Q&A session with students, that he has to masturbate before each writing session or he can’t focus on his work. The undergrads merely giggle as though they’re hearing something daring. At the same time, though, future services like Porn Hub, OnlyFans, or the very idea students will one day fund themselves through uni by selling their bodies to strangers, are an inferno our minds can’t conceive.

In general, we’re a generation who’d rather laugh than moralise – to be ‘judgmental’ is out in the 90s. This is the time (or just after it) when Oliver Reed can turn up blind drunk to a TV discussion programme, aggressively fondle a feminist’s breasts and emerge with his reputation oddly enhanced. Hellraisers like Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris or Keith Allen are celebrated, even if nearly all the world’s bad behaviour goes unwitnessed except by immediate bystanders. There’s no CCTV, no X to tweet their misdemeanours, no phone camera to record it.

And that’s another thing, Generation Z: photography. If you want photos, you’ll have to carry a camera, put film in it and be very sparing with its use. Having your photos printed – expensive – will mean going to Boots or SnappySnaps and then waiting, sometimes for days. ‘If only I’d had a camera on me,’ is something you’ll say in life, again and again.

In comedy, or just around a dinner table, jokes tend to be wilder, and you’d better buckle in. The culture is lighter, less keen to trace the moral and human consequence of every act. At times this is a straight denial of pain; at others it makes that pain easier to shrug off and turn into a funny story. We have different ways of coping, different ethics. We forgive much and don’t blame others so readily for our unhappiness, which we’re pretty sure is just a part of life. Loyalty to friends is more important than loyalty to ideology, and the rules of discretion are still a sort of ideal. Private letters, generally, are not shown to others. Some people can keep secrets; they may not always tell. Should you enter the 1990s with a moral code shaped in 2024, you’ll seem very odd indeed.

The past is a foreign country, L.P. Hartley said, though most foreign countries these days are a lot less different than this. Even those of us who reached adulthood in that time would find, returning to it, a baffling, sometimes jaw-dropping culture to find our way around. As for Gen Z-ers, they’d surely take one look and scurry back mortified to the present day. Maybe it feels that with their retro Calvin Klein perfumes they’re buying a kind of bottled freedom, the scent of an easier age. But those with a real time-machine might find that earlier decades, to paraphrase author Mary Wesley, are a bit like coffee – the smell is nearly always better than the taste.

Comments