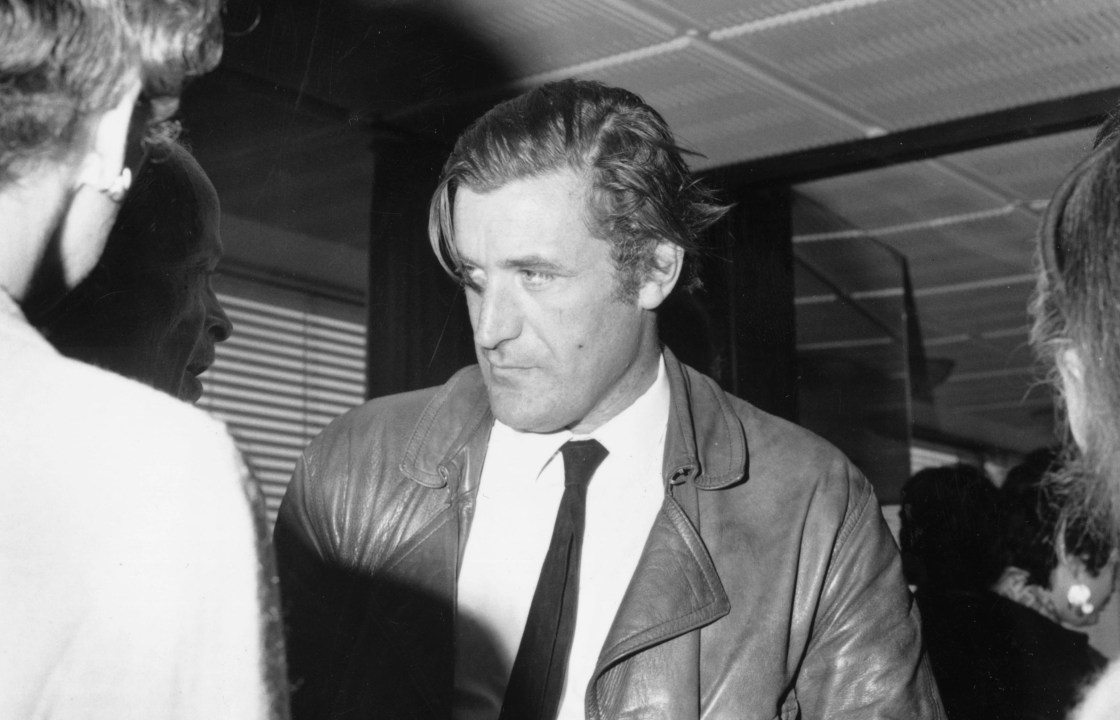

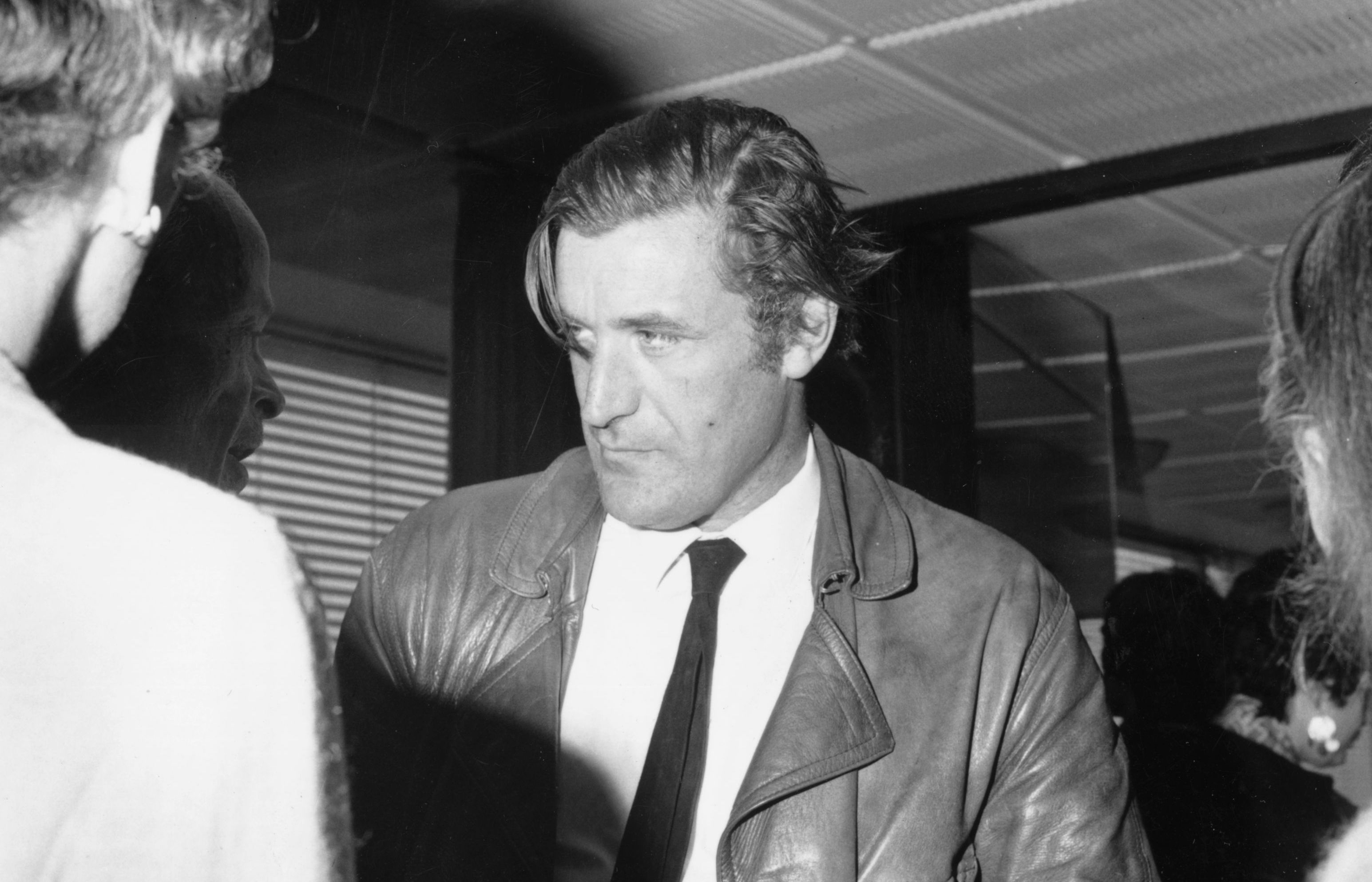

Scandalously, we never studied Ted Hughes at school. As the Poet Laureate is arguably the finest British poet of the 20th century this would be a scandal wherever I attended (‘studied’ would be pushing it) but I attended Calder High in Ted’s home town of Mytholmroyd. Though the grand total of my published poems stands at seven, we share connections, Ted and I. When my first novel was published — set in a fictionalised version of the Calder Valley — I was a guest of the Ted Hughes Festival. As a teenager in the 1980s, I tended Sylvia Plath’s grave. By then Ted was already a bogeyman for some of the area’s more dour feminists, blamed as he was for Plath’s suicide.

Now, thanks to the British Library, Ted’s name is also synonymous with slavery. Apparently a distant relative, Nicholas Ferrar, was deeply involved with the London Virginia Company and so I suppose it’s only a matter of time before Hughes’s books are burnt on the concourse at St Pancras, the blue plaque jemmied from the wall of his modest Mytholmroyd home and his ashes hunted down, hoovered up and jettisoned into space. The fact that Ferrar was born in 1592, fathered no children and almost certainly failed to make Hughes a beneficiary of his will — written in the blood of Africans — is beside the point. Hughes has failed to issue a statement from beyond the grave apologising for George Floyd, rewriting The Iron Man as an allegorical story about white imperialism and thinking up rhymes for Black Lives Matter.

The British Library seems less interested in spreading the love of literature these days than in virtue signalling

Commenting on the decision to besmirch the name of Ted Hughes, the British Library stressed that it had only intended to add the poet’s name to a ‘dossier’ to ensure users were armed with ‘an accurate understanding of those parts of the collections which have direct connections with slavery and other aspects of colonial history’. Slavery, BLM and cleansing the archives of dead white men is obviously more important to the library than, say, ensuring children can enjoy other libraries — including Hebden Bridge library, where I learnt to love books, now closed due to Covid-19 — are reopened.

But then, the British Library (of which I was once a member) seems less interested in spreading the love of literature these days than of virtue signalling. In June the library issued a self-flagellating statement that talked about:

The long-standing lack of BAME representation within the library’s executive management as well as senior curatorial staff, along with the urgent and overdue need to reckon fully and openly with the colonial origins and legacy of some of the Library’s historic collections and practices. The library also needs to ensure that its spaces, events, exhibitions and policies are genuinely inclusive and representative of and for black communities.

In other words, the library is too white — and needs to be more ‘accessible’ for others, who presumably find its modernist design too imposing to enter. How on earth can a library — even one that seems far more concerned with cafes, exhibitions and gift shops than actual books — become more representative of a particular community?

As someone who played an active part in the anti-racism movement in the 1980s, for years I have tended to dismiss such self-aggrandising statements, policies and gestures as well-meaning. But recently I have had a re-think. It’s not that the overwhelmingly white upper-class types who dominate the creative industries mean well: they don’t. They demand people are apologetic about events in which they had no part and received no benefit; view people from certain minorities as victims, urgently in need of a helping hand; and appear to loathe themselves for coming from a background of privilege.

Unlike many of those currently so overwrought about the past, Ted Hughes — who never overwrought anything — was neither a beneficiary nor an apologist. In fact, his dad, a joiner and tobacconist, was of Irish descent and was almost killed at Ypres. What does the British Library think about that?

Comments