In 1984 I was 27. Since leaving school I had done unskilled manual labour, when I could get any. Then l worked as a nursing assistant and then a trainee nurse in an 840-bed psychiatric hospital at Goodmayes in Essex, formerly the West Ham Lunatic Asylum. It was like a walled town. I ate, slept and socialised in there and became institutionalised and a bit mad, I believe.

In ordinary life, among relatively sane people, one becomes fairly confident about the parameters of so-called normal human behaviour. They are narrow parameters, and all the time getting narrower, I think. But if you live in a large mental hospital, these parameters widen drastically, or even disappear altogether. And after a time one comes to relish and prefer the greater variety of human behaviour, and the daily surprises occurring within the crenelated walls, and life outside becomes insipid. I was sacked finally, for, among other things, ‘throwing human excrement at members of the public’.

After that I led an itinerant existence performing more unskilled labour. I mucked out pigs. I cleared builders’ rubble on piece-work. Around this time, too, I had a silly season, and became familiar with the protocol of the magistrates’ court. I was up before the garden gate about once a week, and I was glad of the unusually close attention that was paid to my life by the well-meaning people who work in them.

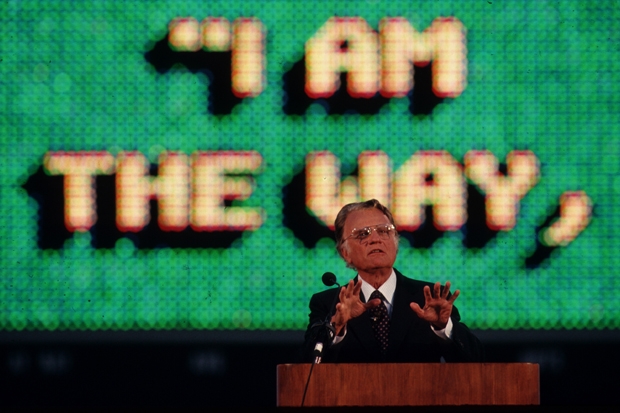

I’ve been thinking about this period of my life a lot lately, after reading in the newspapers about the ‘allegation of a sexual nature’ that has recently been made to the South Yorkshire police about Cliff Richard. It was said to have taken place at a Billy Graham Christian faith rally at Sheffield United’s Bramall Lane football ground in 1985. Apparently, there were 47,000 people packed into the stadium that night, and a total of 200,000 people came to hear him speak over five nights — a surprisingly large number. And reading about that reminded me that Billy Graham also toured Britain’s football stadiums in 1984, one of which was Ashton Gate, home of Bristol City. For I was there on one of the four successive nights he spoke, and the stadium was packed then, too. Thirty thousand spectators, a 2,000-strong choir, the singer George Hamilton IV as a warm-up, and then the world famous evangelist Billy Graham got up to speak.

He spoke softly but mesmerically. ‘Remember the tape at Watergate?’ he said, looking around the stadium. ‘They had everything recorded in the rooms in the White House. They had it on tape. When you stand at the judgment of God he will say to the Angels: “Let’s listen to the tapes!”’

I could well imagine it. I could imagine standing there at the gates, the angels and I gathered around one of those old-fashioned tape recorders, and a manicured angelic forefinger being extended and pressing ‘play’. And I imagined that everybody listening would very quickly have heard all they needed to hear. At that time I had broken about six of the Ten Commandments. I was dwelling in the tents of wickedness.

‘The wages of sin is death,’ said Billy Graham. ‘Hell begins here, but hell is to come as well. You won’t find the answers in drugs or sex. Change your heart, your way of living.’

I knew it already. The man was quite right. I’d been taught about sin since I was small. I knew about rotten wages. I knew about drugs, not that I could ever afford many. I didn’t know much about sex, but I was perfectly willing to lump it in with drugs and hell on Billy Graham’s say-so. He was a powerful speaker. You listened to him. And then came the moment that many of us had been eagerly awaiting. The trademark of a Billy Graham rally was the call to faith; the invitation to come to the front in a public declaration of repentance. And here it came.

‘So now I am going to ask you to get up out of your seat and say, by coming up here, that you are going to open your heart to Christ. You must get up and walk. It may take two or three minutes and you will receive a prayer and some literature.’

I didn’t walk. I was so desperate for a reboot, I climbed over the wall and I pelted on to that pitch, one of the first to arrive in the centre circle. There were many other sprinters. For those like us, Billy Graham might as well have mounted the lectern, cut out the chat, raised a starting pistol above his head, and fired it. More than 2,000 souls ran, walked or sauntered on to the pitch that night and gave their hearts to Jesus. I wonder how they’re all doing.

Comments