‘I wonder what he meant by that,’ King Louis Philippe of France supposedly remarked on the death of the conspiratorial politician Talleyrand. Whenever a person behaves in ways we had not anticipated, it is a Darwinian and often useful human instinct to suspect a rational motive, and seek it out.

So it’s unsurprising that in the world of commentary a whole industry has now arisen in search of an ‘explanation’ of Donald Trump’s various démarches concerning, for instance, Gaza, Greenland and Canada.

And now he’s trying to wreck world trade.

Academic economists have been hauled from their ivory towers, business journalists from their statistical charts, public opinion pollsters from their psephological scrutinies, and even child psychiatrists from their textbooks on infant development, to make sense of the US President’s decrees, speeches and obiter dicta for a bewildered world.

I have especially enjoyed the valiant efforts of fellow journalists on financial pages to find the rationale (if not the wisdom) behind a large nation slapping massive tariffs on its allies and trading partners. There have been charts, forecasts, modellings – all designed to guess or suggest what the President hopes to achieve and why, and to assess his chances of success.

A favourite answer to the apparent riddle of a man who appears able to believe (and say) six impossible things before breakfast has been that Trump must not be taken literally. Another is that ludicrous demands are part of the negotiating strategy of a ‘transactional’ dealmaker. And still the explanations, some more plausible than others, come. Keep them coming, chaps.

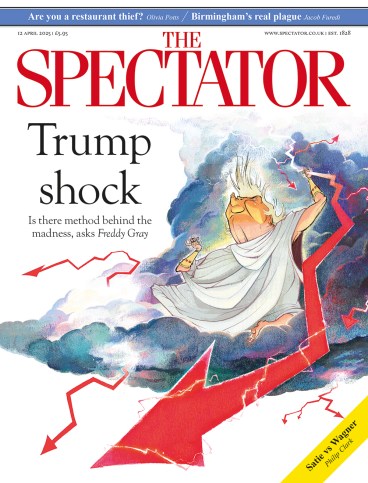

But what if Trump has just gone bonkers? Literally bonkers? What if no other explanation is needed? What if we behold an old man who, as he approaches 80, is simply losing his mind? What if a kind of early-onset (and not all that early) senile dementia is taking place?

After all, Joe Biden isn’t much older than Trump. But with Biden we reached the right diagnosis quickly and stopped looking for more subtle explanations because his symptoms are so very common in ageing individuals. We oldies start forgetting things, losing our thread, showing signs of confusion. For a while (you may remember) there was an attempt to explain away such surface traits as being unconnected with Biden’s deeper wisdom and acuity: as disregardable as, say, a shaky hand or faltering voice. But soon the obvious could not be brushed aside. The President was losing it, and had to be eased out.

Among senior Republicans there will already be a growing recognition that their President has lost his marbles

In Trump’s case, the power, if not the content, of speech remains strong. He still looks vigorous. He is not yet frail physically. Superficially at least, he has lost neither his grip nor his bite. But the power of reason, the ability to reflect and contemplate all sides to a question, the capacity to ask oneself at least privately whether one might be wrong, the suppleness of intellect that marks a person in full command of their mental faculties – might these all be in sharp decline?

The atrophy of what we might call the brain’s muscle is a kind of degeneration whose outward signs may not be immediately evident until what crystallises as a series of terrible decisions becomes impossible to overlook as part of a mental disorder. Whispers of ‘not right in the head’ are heard. Any family business whose patriarch is slowly going gaga but who can still walk, talk and conduct an apparently intelligent conversation will be familiar with the creeping realisation. Fits of obvious insanity become ever harder to ignore.

As so often, Shakespeare created the archetype. Trump is beginning to remind me of King Lear: fitfully reasonable, physically strong but gripped by sudden bouts of madness and a kind of lunatic stubbornness – a vicious hardening of the mental arteries. George III’s illness took him more stealthily, returning him for long periods to sanity, until senior figures felt obliged to make legislative provision for a regency.

Winston Churchill, though never mad, had slipped into a mild senescence before he ceased to be prime minister. Learned volumes have been written about ailing leaders in power and many examples are cited – but there have surely been many more whom we never suspected: old fools kept on their feet by discreet courtiers as their powers ebbed.

I remember watching General Franco’s new year message on TV in Spain in 1973. You could all but see a strong arm behind his back keeping his spine vertical as the shrunken old man, a pile of bones inside a stiff, bemedalled military uniform lisped his now-croaky way towards his concluding: ‘¡Que viva España!’

But Franco had long lost real power. Trump has not. In his first term, though his utterances were sometimes typically deranged, his actions – far more restrained – evidenced a sense of the limits of the possible. We can already be confident that among senior Republicans who still publicly support him there will be a growing private recognition that their President has lost his marbles, and with them that better part of valour.

Public silence betrays, I suspect, a realisation that the US Constitution makes it difficult, if not impossible, to remove a sitting president still in possession of his elementary faculties except through impeachment. But in politics, even constitutional politics, where there’s a will, a way can sometimes be found.

The imperative with Trump is to hobble him. If or when his policies begin to redound to the clear disadvantage of those who voted for him, if the next midterm elections show powerful evidence of national disgruntlement, if he loses the congressional control he now has, the President’s fair-weather friends will begin to peel away. Once that starts, the abandonment will become headlong: I’ve observed often enough in British politics how shamelessly fast such friends depart once the weather turns.

And it will turn. Our own Prime Minister may be unwise to seek the role of go-between with a White House incumbency that may soon be regarded as a moment of quite literal madness – and sooner than some think. I remain to be convinced that the world order has changed for ever.

Comments