When someone one day writes a true history of Scotland during the baleful tenure of Nicola Sturgeon and reflects on what brought about her downfall as first minister, ‘Isla’ Bryson might be worth a footnote but J.K. Rowling surely merits a chapter. No one has managed to articulate the opposition case to Sturgeon with the verve, intelligence and penetrating wit of the Harry Potter author.

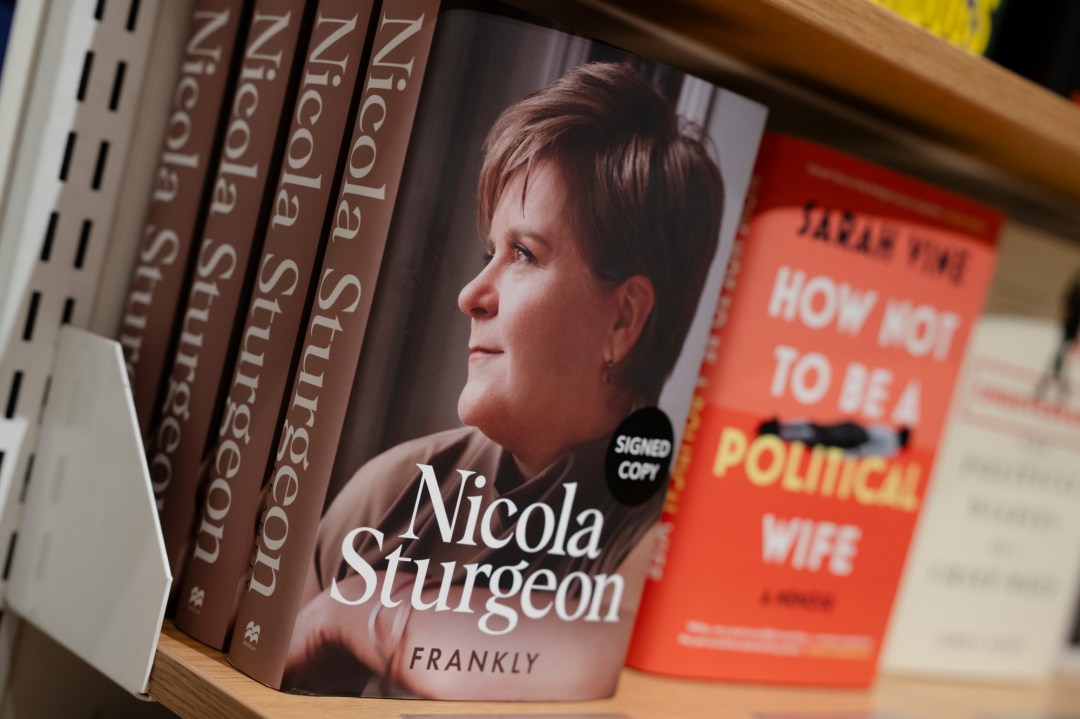

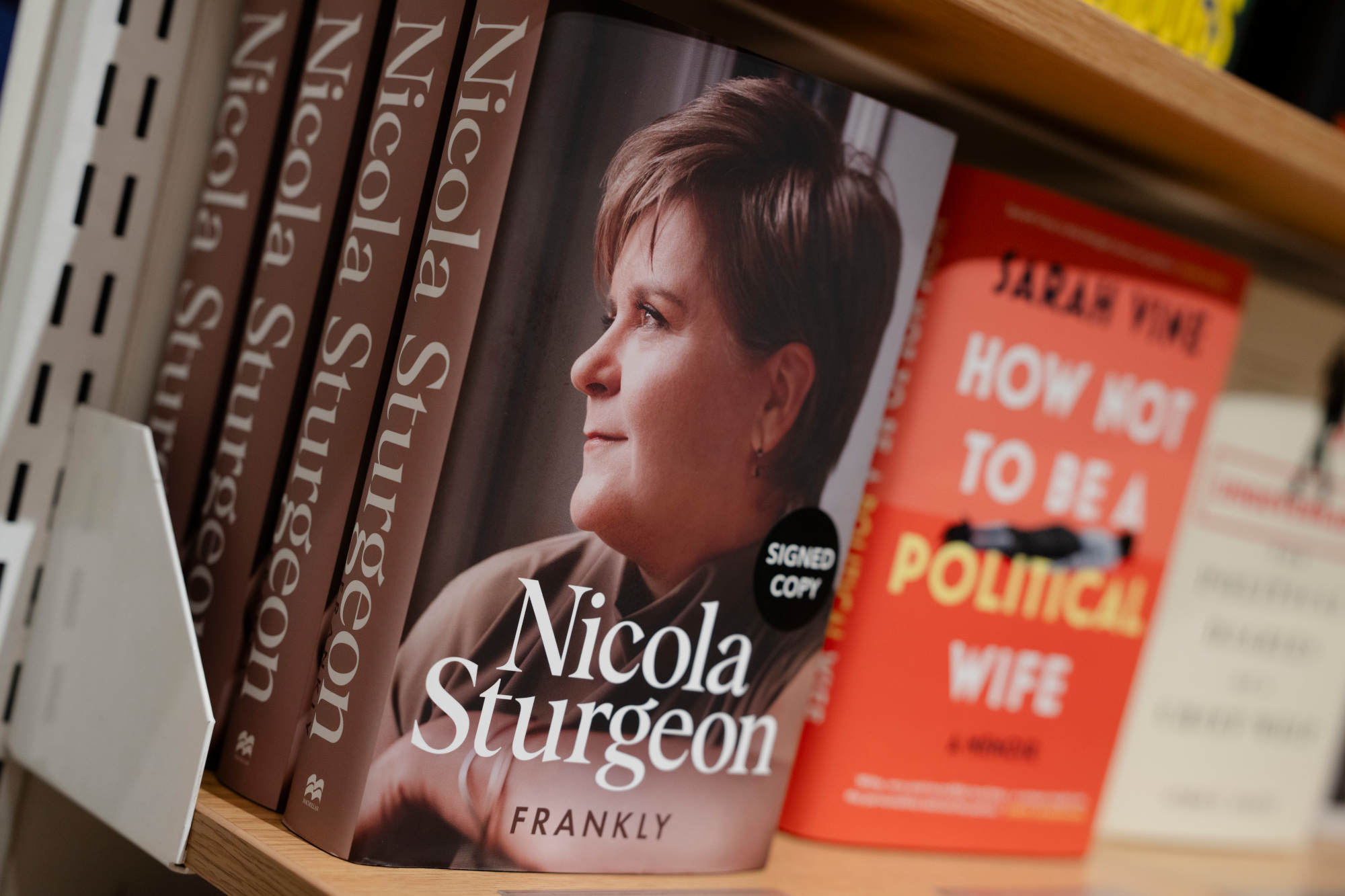

Rowling’s review of Frankly, Sturgeon’s recently published memoir, is in many ways as brilliant as her other mainly tweeted thrusts. It is incisive and damming, outclassing her adversary and doing so with courage humour and originality. In other ways though it misses the mark, failing, as many observers of Scottish politics do, to see the details in the rotting wood for the petrified forest of trees.

What is good is Rowling comparing Sturgeon to Bella Swan, heroine of the Twilight series, in that it conjures the image of blood being sucked from the body politic of Scotland (the SNP have been positively vampiric in their predations). It also highlights the eternally adolescent quality of the Sturgeon persona, a woman who had never had a serious job outside politics, a woman who avoids all serious scrutiny (even yesterday she cancelled what could have been uncomfortable interviews with the media) a woman who didn’t learn to drive until she was in her 50s, a woman who recently got a tattoo.

Sturgeon never moved on from her teenage obsession with independence. She never seriously addressed independence’s huge practical obstacles or seemed interested in doing so, and certainly does not attempt this in Frankly. She never seems to have acquired wisdom or depth or humility, and never truly managed to emerge from the shadow of a charismatic mentor – Alex Salmond.

Rowling takes a well-aimed swipe too at Sturgeon’s propagandistic assertions that the 2014 referendum was a glorious inclusive positive exercise in democracy, a revisionist mantra from the still active veterans of the Yes camp repeated so often it’s in danger of becoming accepted as gospel truth. The actions of those Yes voters at the time would suggest otherwise. As Rowling says:

‘Oddly, this message didn’t resonate too well with No voters who were being threatened with violence, told to fuck off out of Scotland, quizzed on the amount of Scottish blood that ran in their veins, accused of treachery and treason and informed that they were on the wrong side of, as one “cybernat” memorably put it, “a straightforward battle between good and evil.”’

She is also right to have a dig at Sturgeon’s ‘London friends’ who were dazzled and beguiled by the first minister, and couldn’t see or were not interested in hearing about her and her party’s endless failings. Rowling points out that these serial calamities get no serious mention in the book. As she rightly says, the omission of any reference to Scotland’s soaring drugs deaths figures in particular is, frankly, appalling.

Rowling is also relentless and remorseless in highlighting the dangers of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill (GRRB) and the culture of intolerance and vilification of any criticism Sturgeon engendered in its wake. Many political commentators focus on this piece of legislation in terms of its apparent consequences for Sturgeon’s career, for her party, and for the broader independence cause, ignoring or downplaying the surely more important point that it relegated biological women to a sub category, putting them potentially in harm’s way, and then told them to shut up and live with it. As Rowling puts it:

‘She’s caused real, lasting harm by presiding over and encouraging a culture in which women have been silenced, shamed, persecuted and placed in situations that are degrading and unsafe, all for not subscribing to her own luxury beliefs.’

But where Rowling perhaps misses the target is in taking Sturgeon’s support for the GRRB at face value, in assuming that her interest in self-ID was genuine and sincere. She says that Sturgeon was ‘unshakeable in her belief that if men put on dresses and call themselves women they can only be doing so with innocent motives.’

Really? Not everyone agrees with that, starting with Alex Salmond who once remarked that Sturgeon had never shown any interest in the issue of gender self-ID in the long time that he had known her, hinting in that Salmond-ish way that perhaps something else was going on.

To find out what that something might be, one must, as so often with Scottish politics, depart the mainstream and head to the media by-waters, to the bloggers that pick through the rank smelling weeds of Scottish politics. Robin MacAlpine, a freelance journalist and former director of the Common Weal think tank (and independence supporter) has charted Sturgeon’s shifting positions on gender issues over her career and sees them in purely strategic terms. As he puts it:

‘Sturgeon and Murrell operated through fear… and their most aggressive punishers were young, digitally savvy activists – who happened to be strongly committed to trans politics. Sturgeon’s most effective thug squad had to be kept placated. That (I believe) is why Sturgeon was so quick to announce gender ID legislation and so slow to produce it. She needed their rage, but not the legislative headache…’

Which might explain the initial interest. But why then actually push for full enactment of self-ID? Why not just fudge the issue? MacAlpine explains:

‘Then something else happened; the fall-out of the Salmond trial and the parliamentary inquiry. This nearly finished her career and some of the most dangerous revelations were down to her lack of a parliamentary majority when the Greens voted for disclosure. It is really important to understand the significance of this. Sturgeon was utterly desperate to close down the Scottish Parliament as a body that would scrutinise her and the way to do that was to have an overall majority bound by collective responsibility.’

MacAlpine points out that Sturgeon could have had a parliamentary majority with the Scottish Greens in 2016. But she didn’t pursue one, preferring to pass most of her legislation with votes from the Scottish Tories. MacAlpine calls the Bute House agreement an ‘anti-transparency’ move which he believes was designed to ensure total control at a critical moment and ensure the Greens were friends not foes.

In other words, the GRRB perhaps had little to do with trans rights and was more about keeping a lid on a potentially explosive scandal. In which case, the cause of independence, her party’s reputation, the women and girls of Scotland were expendable.

Rowling ends by admitting she may have missed the point of Frankly, that perhaps it isn’t intended to entertain, or enlighten but to serve as a CV distinguisher, and assist her on the way to her long coveted ‘cushy sinecure’ with UN Women. Well perhaps, though cynics might suggest that unlike the ferry Sturgeon ‘launched’ back in 2017, that ship has sailed. More likely Frankly is not just a CV distinguisher. It may just be a pre-emptive plea for mitigation.

Comments