Even before the final result of the US Presidential election was known, the British left was ready with its hot takes. Momentum, which continues to proudly hold aloft the flickering flame of Corbynism, was amongst the first out of the traps, claiming that Joe Biden’s failure to achieve a landslide victory confirmed, ‘what we already know: that corporate centrism cannot deliver a decisive defeat to insurgent right-wing populism or deliver real change’.

Expect more of this kind of thing from across the Labour party: somehow or other events in the US will be magically used to authenticate already-entrenched positions. Since the parallel rise of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, the party’s left and right have used events across the Atlantic as a proxy to advance their more parochial agendas, forgetting that the United States is a foreign country – they do things differently there.

This is not a new development. Labour leaders have long felt a cultural – if not ideological – affinity with the United States. That was partly thanks to exchange programmes conferences, lecture tours and university fellowships, many of which were indirectly funded by the CIA. But there were other more banal reasons for this Special Relationship: both Tony Benn and David Owen had American wives. The United States they saw was one largely of their own imagining: a benign country populated by cosmopolitan north-eastern Democrats and a few trade union leaders, one in which class distinctions barely existed and, if racism was a problem, it was on the way to being eradicated. Since then the Reagan years, the George Bush presidency and – most cruelly – the Trump presidency have somewhat lifted the scales from their eyes.

But the United States is still a useful reference point for Labour leaders looking to sprinkle themselves with a bit of Washington glamour. Harold Wilson deliberately evoked John Kennedy’s successful ‘New Frontier’ rhetoric when he called for a ‘New Britain’ in the run up to the 1964 general election. Bill Clinton’s winning 1992 campaign meant Tony Blair was happy to be seen as ‘Clintonizing’ his party by taking Labour in a more moderate direction. Less successfully, Ed Miliband – who spent much of his childhood in the US – tried to evoke the power of the ‘American Dream’ when he referred to the ‘British Promise’ in 2011.

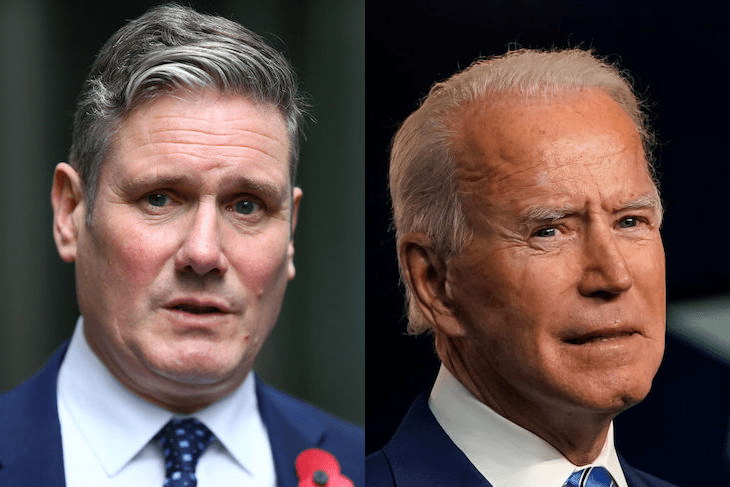

What lessons will Keir Starmer draw from the Biden campaign? As with Momentum, it is likely he will see what he wants to. Unlike his Corbynite critics, Starmer will likely see that a centre-left candidate struggled to make a strong impact on Rust Belt voters, thanks both to the primal appeal of a right-wing populist incumbent and the alienating cultural politics of his own party. Certainly, some US commentators suggest the latter factor played an important part in the Democrats’ disappointing performance on 3 November.

This is not, however, a lesson Starmer needs to learn, with his impressive personal poll leads over Boris Johnson while the Labour party struggles to overshadow the Conservatives. Starmer already knows that his party has to reconnect with those Red Wall voters who had slowly drifted away from his party over the last four or more elections and were fatally attracted to the Johnsonian persona in 2019. This is the reason why Starmer highlighted his patriotism in his recent Labour conference speech. Even so, it will be surprising if Starmer and his allies will not exploit what looks likely to be Biden’s slow crawl into the White House as a salutary lesson for a Labour party that has still not fully come to terms with its fourth defeat in a row. As they attempt to shift their party away from Corbynism, some will undoubtedly cite Biden’s experience to justify their strategy.

Steven Fielding is Professor of Political History at the University of Nottingham. On 14 November 2020 he presents for BBC Radio 4 ‘How to Come Back from the Brink’.

Comments