The NHS vaccination programme has reached its latest big milestone of offering a jab to everyone in the top nine priority groups three days ahead of schedule. Everyone in government and the health service is celebrating. Boris Johnson has been busy thanking ‘everyone involved in the vaccine rollout which has already saved many thousands of lives’, while NHS chief Sir Simon Stevens has said:

‘Thanks to our NHS nurses, doctors, pharmacists, operational managers and thousands of other staff and volunteers, the NHS Covid vaccination programme is without a doubt the most successful in our history. It’s one of our tickets out of this pandemic and offers real hope for the future.’

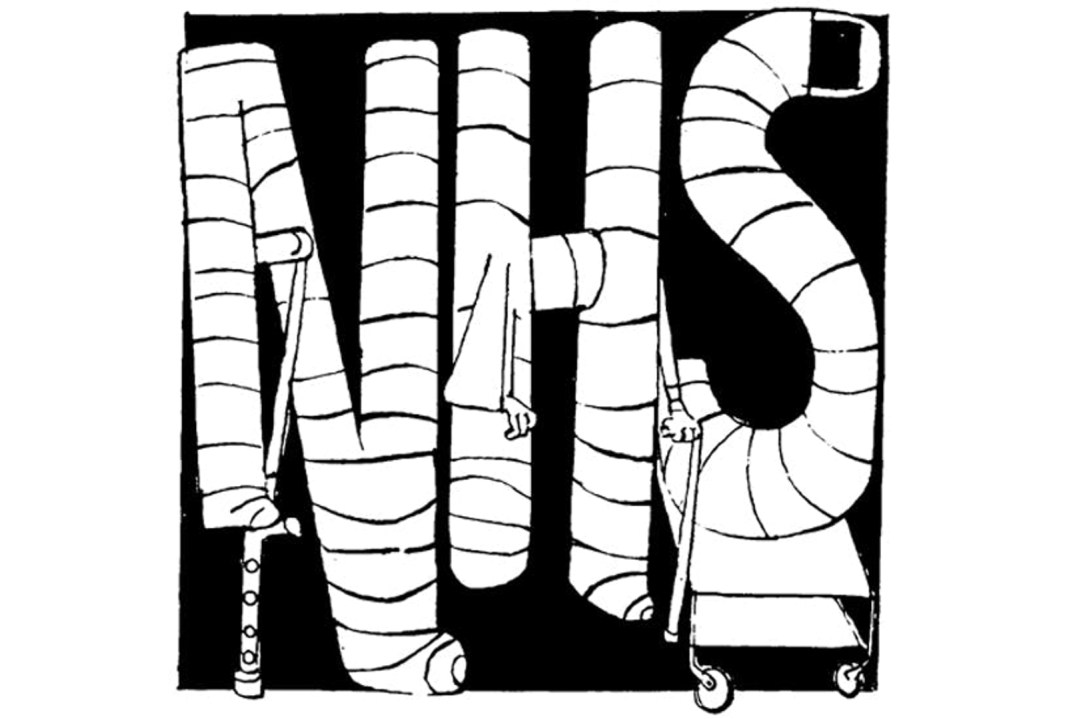

The NHS backlog and levelling up are just two issues alongside many other policies that have been pushed to one side in the rush to deal with coronavirus

There is naturally plenty of jostling to take credit for the success of this programme, with those in the NHS placing a heavy emphasis on the fact that it was drawn up by the health service and administered by the health service. The implicit contrast that is always drawn is with the Test and Trace programme, which despite bearing the NHS brand has not been an in-house job and has not been a success.

Ministers, meanwhile, are also quick to point out there wouldn’t be as many jabs going into as many arms if it hadn’t been for the Vaccine Taskforce that bought the doses in the first place: and that Taskforce was set up by them and its head Kate Bingham appointed by Boris Johnson.

But what’s almost as interesting is the way in which the vaccination programme is being used as a way of making certain arguments about the health service in the future.

Stevens recently wrote a piece for the Times in which he said the programme ‘has shown the practical benefits and provided a blueprint for the future’ when it comes to integration of the health service. Stevens’s point was largely aimed at the integrated care systems which are being set up currently and being put onto a statutory footing in the forthcoming NHS reform legislation.

But there is also a case being made for the government to take the same approach to the backlog in treatment caused by the pandemic as it did with the vaccination programme (and indeed the Test and Trace programme and its many problems). This approach was one of ‘by any means necessary’: throwing money at the problem, putting a huge amount of government time and focus into these programmes, and discarding other issues until a later date.

A phrase you hear a lot now in Westminster and in the health service is ‘the might of government’, because many have been impressed that when the government really wants something to happen, it can realise that much quicker than previously seemed possible. It’s not just something you hear in relation to health: MPs in northern seats who are impatient to see progress in the ‘levelling up’ agenda also want the might of government to be focused on this policy area.

The chances of the might of government staying this focused as Britain emerges from the pandemic are pretty slim. The NHS backlog and levelling up are just two issues alongside many other policies that have been pushed to one side in the rush to deal with coronavirus. A feature of politics for the next few months may well therefore be disappointment as the might of government shrinks once again.

Comments