W.H. Auden, in his essay on detective fiction, ‘The Guilty Vicarage’, asked: ‘Is it an accident that the detective story has flourished most in predominantly Protestant countries?’ He was thinking about confession and how this changes things. In Auden’s view, murder is an offence against God and society and when it happens it shows that some member of society is no longer in a state of grace. But confession gives a transgressor a means of returning to a state of grace, so the moral order can be restored without recourse to a policeman.

You wonder: do ghost stories too flourish most in a Protestant (or formerly Protestant) society? There have always been ghost stories and they reflect the beliefs of the people who told them – for instance, when Christ’s apostles saw him walking on water, their first thought was that he was a ghost. If access to confession could change the dynamic of a detective story, there is another Catholic doctrine which could alter the workings of a ghost story and that is purgatory and the possibility of prayers for the dead.

While the concept of the unquiet spirit is common to all the stories, the ghosts’ aims in appearing to the living may differ. St Thomas Aquinas poses the question of whether the souls who are in heaven or hell are able to go from hence. He answers: ‘According to the disposition of divine providence, separated souls sometimes come forth from their abode and appear to men… It is also credible that this may occur sometimes to the damned, and that for man’s instruction and intimidation they be permitted to appear to the living; or again in order to seek our suffrages [prayers], as to those who are detained in purgatory.’

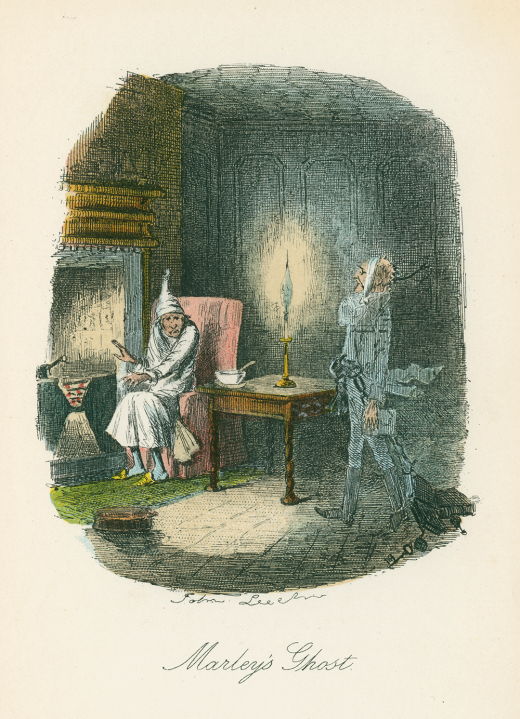

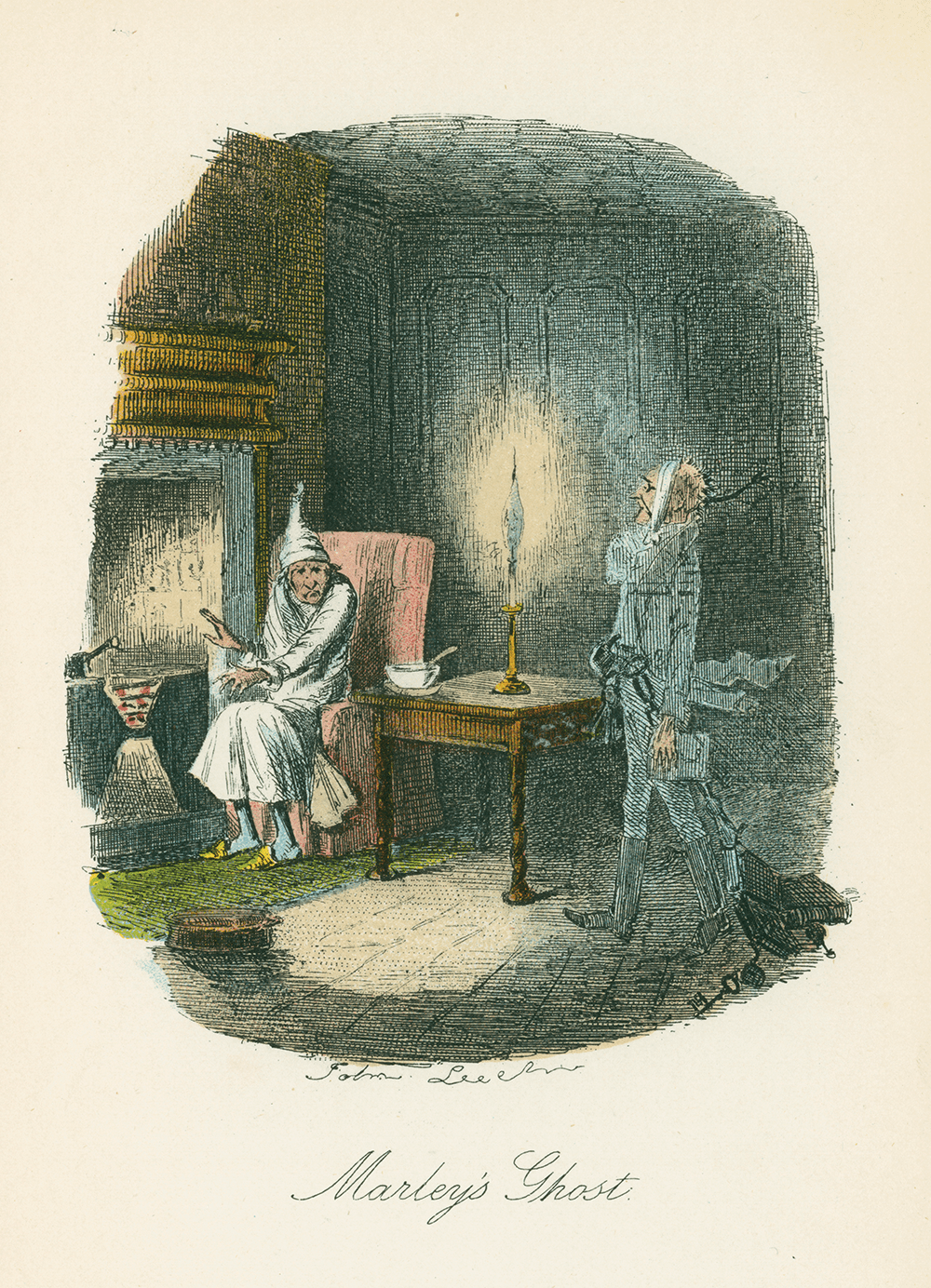

In other words, God may allow damned souls and those in purgatory to appear to the living but the object of the two parties is different. The damned appear to the living for ‘instruction and intimidation’, to show their living friends or relatives the necessity of mending their ways. In that respect Marley’s ghost is a good example of the type: he appears to Scrooge to exhort him to mend his ways and not follow him to perdition and he succeeds.

The other type, the soul in purgatory, who can be helped in various ways, is not a Protestant ghost at all. For the Protestant belief is that as a tree falls, so must it lie, and there is nothing the living can do for the dead. There’s an interesting collection of medieval ghost stories edited by Andrew Joynes, and what’s striking about them is how often ghosts exhort the living to shorten their punishment by, for instance, putting right their bad actions, perhaps usury, and/or praying for the tormented soul. And if the living friend does what is asked, the poor soul may reappear to say that he’s now sorted. (Some bad people, of course, are damned irrevocably.)

What you don’t often get in Catholic medieval stories is a ghost instructing the living to take revenge on his behalf. Hamlet’s father’s ghost is an oddity; he wants Hamlet to kill his uncle in revenge for his own murder as a way of restoring the moral order. It is not about liberating the father from purgatory or edifying Hamlet so he leads a better life. In fact the ghost tells Hamlet that he is undergoing the pains of purgatory because he was cut off in his sins before he could confess them (a very medieval preoccupation) and has been released for a short time to deliver his message. But a good Catholic ghost would have wanted prayers for his soul, not revenge on his killer.

And this is the Protestant tendency in ghost stories: the aspiration to set the record straight on Earth rather than to help the dead get to heaven. Walter Scott’s story ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ is about making clear that an old lady who frightens the wits out of a distinguished soldier is haunting a room where ‘incest and unnatural murder’ took place. Sheridan Le Fanu’s creepy story ‘Madam Crowl’s Ghost’ features a horrible old woman who appears to a little girl after her death surrounded by flames – no prizes for guessing where she was – but also to show where she had locked up her little stepson to die. So there’s an earthly, restorative point to her appearance.

A good Catholic ghost wouldhave wanted prayers for his soul, not revenge on his killer

M.R. James is a curiosity since he often makes clear that ghosts have the power to harm the living, even though the living may be sorry for their bad actions. So the poor man who dug up an Anglo-Saxon crown is hunted to his death on the shore, even though he has restored the crown to its barrow and talks about bringing in ‘the Church’. In ‘Count Magnus’, the rash young man seems to invoke the villainous nobleman unconsciously, and when he returns to life the ghost breaks all the rules and follows the poor man over the sea to England, whereas in a proper rules-based supernatural order, he would not be able to cross water.

As for Bram Stoker’s ‘The Judge’s House’, it is horrible precisely because the demonic rat has the power to destroy the young man, and the only thing that gives the creature pause is when the young man throws a Bible at it.

That is where Protestant ghost stories fall down: in the ability of ghosts to harm even well-meaning or penitent souls, which is not what a just God would allow. G.K. Chesterton’s original Father Brown – that is, the real-life Irish priest Father John O’Connor – was impatient with all this: ‘I had always been a hater of sham ghost stories and a collector of real ones,’ he wrote in his memoir, noting how ‘untrue stories give themselves away, whereas true stories do not vary very much, but keep the rules of the spirit world. Even lawless spirits cannot vary their antics very much… So that if the elect can only keep their heads, they are not taken in. It is even possible to cow false spirits by superior will and courage.’

In this view, if the prudent individual invokes God’s help, not much will go wrong. He recounts a ghost story featuring Chesterton’s secretary, Miss Allport, a sceptic on the supernatural, who took a suspiciously cheap flat in Bloomsbury. Once there she felt sure that she was being watched; in the night she was kept awake by loud and unaccountable bangs. The next day: ‘Chesterton noticed her haggard appearance, and she told him all about it. “You must have a crucifix on that door,” he said. That afternoon he went to London with her and at Burns and Oates in Baker Street bought her a one-and-six-penny crucifix, instructing her to nail it on the inside of the door. She was no more molested in any way, she said, and was still residing in the flat at the time of speaking.’

In a nutshell, Catholic ghosts know where they stand in the supernatural order; Protestant ghosts are more unruly. But maybe the Proddy ghost makes a better story.

Comments