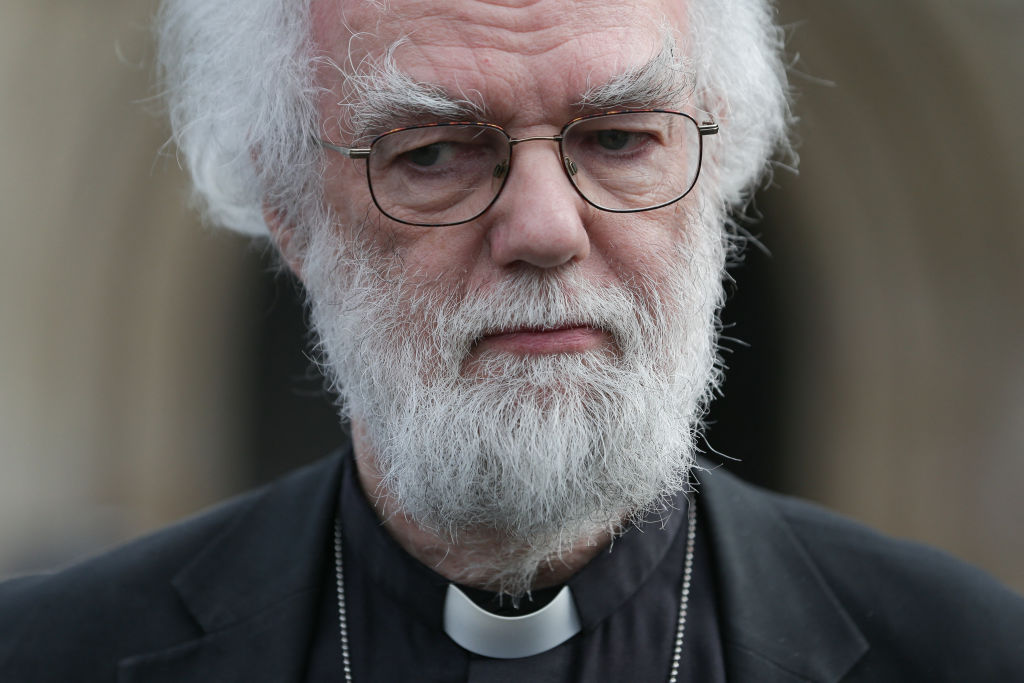

Rowan Williams used his Reith lecture on religious liberty to make a plea to religious believers: don’t be afraid of being an awkward misfit. The former Archbishop of Canterbury called on believers to challenge the social consensus – even on contentious issues like gay marriage.

His view is that religion is not a private affair, but impinges on public life. It does so, he said this week, in ways that the liberal order will find annoying, even disruptive. Believers appeal to transcendent truths beyond the ‘prevailing social consensus’, according to Williams. As a result, he said, they are rightly wary of an order whose only basis is human law, which is defined by majority opinion. But, he added, religious has a key role to play in standing against ‘the absolutism of the status quo’, and against majoritarianism, whether secular or religious. It is through such dissent that great moral advances are made, Williams suggested; it takes a minority with a profound conviction to challenge the prevailing consensus of the day.

In short, Williams wants to embolden religious believers to speak up on prevailing views, whether these are secular, liberal or a mix of religious and nationalist. But of course the message is mainly directed to people living in liberal societies. So perhaps the main message of Williams’s lecture is this: don’t be cowed by the seeming authority of liberal democracy; it is just another human system, and its rhetoric of toleration is a subtle form of intolerance, or ‘repressive tolerance’, for it delegitimises the otherness of religion, its appeal to an authority beyond the rational consensus.

Williams wants to embolden religious believers to speak up

Williams makes a valid point, but at the cost of neglecting a wider issue. He is right to say that any sort of political consensus is open to criticism, and to say valid criticism might come from religion, with its rationally unjustifiable absoluteness. But he is wrong to paint liberal democracy as just another form of political order, and a particularly subtle threat to religion. The bigger picture is that liberal democracies are far better at protecting people’s liberty than other political systems. Why shouldn’t Christian thinkers sometimes celebrate this? And why not point out the deep Christian roots of liberal democracy?

Instead of reflecting on the deep affinity between Christianity and liberal values, Williams and other ‘post-liberals’ are anxious to show how critical they are of liberal hubris. There is a role for such criticism. But it should be part of a nuanced approach, in which the basic goodness of the liberal state is affirmed. Indeed it should be seen as God’s gift to modernity. For decades now, theology has been dominated by a one-sided critique of liberalism. It’s a dated perspective, rooted in the postmodern post-Marxist thought of the 80s and 90s. Time for a pendulum swing.

Comments